Sean Spicer, the man still showing the residual effects of a former incarnation as a deer basking in headlights, was left foundering once again during yet another painful-to-watch press briefing.

Having already used two stacks of paper to try and make an important political point, the White House Press Secretary struggled to defend President Trump’s claims that Barack Obama had him wiretapped during the election campaign.

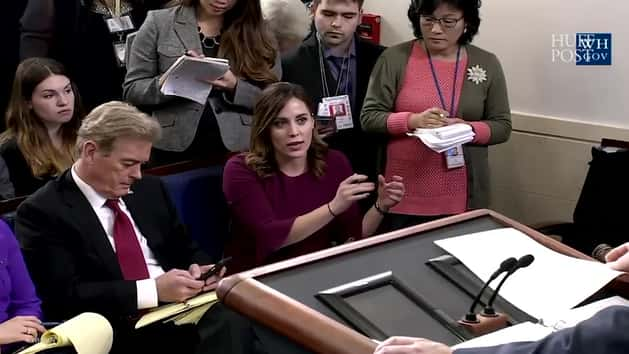

Let’s take a closer look...

Here are some actual facts from the Associated Press.

The Justice Department, not the president, would have the authority to conduct such surveillance, and officials have not confirmed any such action.

Through a spokesman, Obama said neither he nor any White House official had ever ordered surveillance on any US citizen.

Obama’s top intelligence official, James Clapper, also said Trump’s claims were false, and a U.S. official said the FBI asked the Justice Department to rebut Trump’s assertions.

Why turn to Congress, Spicer was asked on Monday.

”My understanding is that the president directing the Department of Justice to do something with respect to an investigation that may or may not occur with evidence may be seen as trying to interfere,” Spicer said. “And I think that we’re trying to do this in the proper way.”

He indicated that Trump was responding to media reports rather than any word from the intelligence community.

Other officials have suggested the president was acting on other information.

Sen. John McCain, chairman of the Armed Services Committee, said Monday that Trump needs to give more information to the American people and Congress about his wiretapping accusations.

“The dimensions of this are huge,” McCain said. “It’s accusing a former president of the United States of violating the law. That’s never happened before.”

As for the genesis of a possible wiretap, it is possible the president was referring to the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, a 1978 law that permits investigators, with a warrant, to collect the communications of someone they suspect of being an agent of a foreign power.

That can include foreign ambassadors or other foreign officials who operate in the U.S. whose communications are monitored as a matter of routine for counterintelligence purposes.

The warrant application process is done in secret in a classified process. But, as president, Trump has the authority to declassify anything. And were such a warrant to exist, he could theoretically move to make it public as well.

If the president demands to know what happened, “the Justice Department can decide what’s appropriate to share and what’s not,” said Amy Jeffress, another former Obama administration national security lawyer, reports the Associated Press.

The Justice Department applies for the warrants in a one-sided process before judges of the secretive Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court.

Permission is granted if a judge agrees that there’s probable cause that the target is an agent of a foreign power.

Though the standard is a high bar to meet, applications are hardly ever denied.

Targets of wiretaps are not alerted that their communications are being recorded.

Defendants later charged in the criminal justice system may ultimately learn the government intends to use at trial evidence collected through a FISA warrant, but they are not presented with the actual application for a warrant.

“Unfortunately, the public has never seen an actual FISA application over nearly 40 years, so we don’t know exactly how the FISA Court has applied or interpreted the probable cause standard in this context,” Patrick Toomey, an American Civil Liberties Union staff attorney specialising in national security, said in an email.

Trump also could have been referring to wiretapping authorised under the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968.

The Justice Department can obtain a warrant for that surveillance by convincing a judge that there’s probable cause to believe the target has committed or is committing a crime.

Rep. Jason Chaffetz says it’s possible that federal employees could have used tactics other than a phone wiretap.

He noted that “stingrays” - suitcase-sized devices that imitate a cellphone tower - allow police to zero in on a phone’s location.

The phones don’t have to be in operation, and some versions of the technology can even intercept content, like texts and calls, or pull information stored on the phones.

“There are other ways and other tools at the disposal of the federal government that have been used in the past,” he told Fox News on Tuesday.

For Congress, getting to the bottom of this should not be difficult, said Dan Jones, a former Senate investigator and currently president of the Penn Quarter Research and Investigations Group.

If there was no such warrant, he said, the next step would be to ask the president why he made the claim.