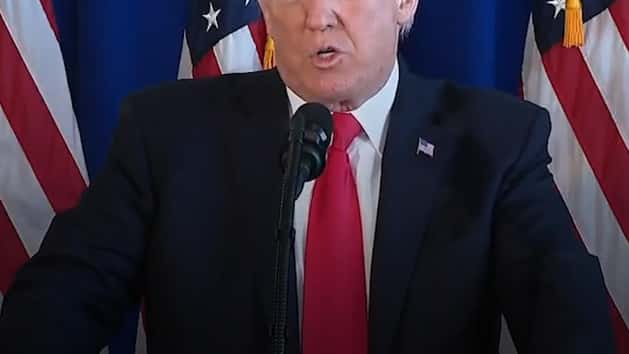

It’s been over a year since Donald Trump was elected president of the United States, and he’s spent much of that time reaffirming the legacy of racism upon which he built both his campaign and his real estate business.

From taco bowls and travel bans to “birtherism” and scorn about Black Lives Matter, HuffPost has kept running lists during and after the election detailing examples of Trump’s racism dating as far back as the 1970s. We’ll continue to document those incidents here as they happen.

He said immigrants from Africa and Haiti come from “shithole countries”

In a meeting with lawmakers in the Oval Office in January 2018, Trump argued against restoring protections for immigrants from Haiti and African nations, describing them as “shithole countries,” sources told The Washington Post and NBC News.

“Why are we having all these people from shithole countries come here?” the president reportedly said. “We should have more people from places like Norway.”

“Certain Washington politicians choose to fight for foreign countries, but President Trump will always fight for the American people,” White House principal deputy press secretary Raj Shah said in a statement later that day.

The following day, Trump claimed on Twitter that he hadn’t used those specific words, but Sen. Dick Durbin (D-Ill.) ― who was in the room at the time ― swiftly contradicted him, saying that the president had in fact “said these hate-filled things and he said them repeatedly.”

He asked a Korean-American intelligence analyst where “your people” are from, and implied that her ethnic background should determine her job

After Trump’s “shithole countries” slur, officials told NBC News that in fall 2017, a Korean-American intelligence analyst was briefing Trump on a situation in Pakistan when the president asked her: “Where are you from?”

When she told him she was from New York, Trump was reportedly “unsatisfied and asked again.”

Referring to the president’s hometown, she offered that she, too, was from Manhattan. But that’s not what the president was after.

He wanted to know where “your people” are from, according to the officials, who spoke under condition of anonymity due to the nature of the internal discussions.

Trump’s question was a variation of “where are you really from?” ― a question commonly asked of people of color, particularly Asian-Americans, who are often seen as “the other.”

Referring to that analyst as “the pretty Korean lady,” Trump also asked why she was not working on issues surrounding U.S. negotiations with North Korea, suggesting that he believes people’s ethnic backgrounds should determine their jobs.

He took more than 48 hours to denounce the white supremacist violence in Charlottesville, Virginia

Trump came under fire in August for his response to a white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, that left one counter-protester dead.

The day of the rally, Trump said he condemned the “egregious display of hatred, bigotry and violence on many sides,” without specifically mentioning the white supremacists who organized the rally and the one who ran over a woman with his car.

“The president’s remarks were morally frustrating and disappointing,” former NAACP president Cornell Brooks said at the time. “While it is good that he says he wants to be a president for all the people and he wants to make America great for all of the people, let us know this: Throughout his remarks he refused to” call out white supremacists by name.

“Racism is evil, and those who cause violence in its name are criminals and thugs, including the KKK, Neo-Nazis, white supremacists and other hate groups that are repugnant to everything we hold dear as Americans,” he said following the immense public pressure.

Some of his top advisers and Cabinet picks have histories of prejudice

Since winning the election, Trump has picked top advisers and cabinet officials whose careers are checkered by accusations of racially biased behavior.

Steve Bannon, Trump’s chief strategist and senior counselor, was executive chairman of Breitbart, a news site that Bannon dubbed the “home of the alt-right” ― a euphemism that describes a loose coalition of white supremacists and aligned groups. Under Bannon’s leadership, Breitbart increased its accommodation of openly racist and anti-Semitic writing, capitalizing on the rise of white nationalism prompted by Trump’s campaign.

Retired Lt. Gen. Mike Flynn ― who worked as Trump’s national security adviser until resigning in February amid revelations that he discussed U.S. sanctions against Russia with that country’s ambassador ― has drawn scrutiny for anti-Muslim comments he has made over the years. In February, Flynn tweeted that “fear of Muslims is rational.” Over the summer, he said that there is a “diseased component inside the Islamic world” that is like a “cancer.” Flynn has defended Trump’s past proposal of banning Muslim immigration and suggested he would be open to reviving torture techniques like waterboarding.

In addition, Trump has nominated Sen. Jeff Sessions (R-Ala.) to be attorney general of the United States. The Senate refused to confirm Sessions as a federal judge in 1986 amid accusations that he’d made racially insensitive comments, including that the only reason he hadn’t joined the Ku Klux Klan was because members of the extremist group smoked marijuana. Civil rights groups condemned Trump’s nomination of Sessions, while leading white nationalists celebrated it.

And Steve Mnuchin, who Trump tapped to serve as Treasury secretary, faces allegations of profiting from racial discrimination. As a hedge fund manager, Mnuchin purchased a troubled mortgage bank, sped up its foreclosure rate and sold it for a killing several years later. Along the way, Mnuchin’s bank came under fire from housing rights groups for racist practices like lending to very few people of color and maintaining foreclosed-upon properties in neighborhoods that were predominantly black and brown less than in white neighborhoods.

He denied responsibility for the racist incidents that followed his election

While the hate speech and racist violence emboldened by his campaign only escalated after his win, Trump downplayed the incidents and half-heartedly denounced them.

There were nearly 900 hate incidents across the U.S. in the 10 days following the election, a report released last month by the Southern Poverty Law Center found. Those attacks include vandals drawing swastikas on a synagogue, schools, cars and driveways; an assailant beating a gay man while saying the “president says we can kill all you faggots now”; and children telling their black classmates to sit in the back of the school bus.

In nearly 40 percent of those incidents, the SPLC found, people explicitly invoked the president-elect’s name or his campaign slogans.

The Council on American-Islamic Relations and the Anti-Defamation League have also tracked significant growth in racist and bigoted attacks.

“We’ve seen a great deal of really troubling stuff in the last week, a spike in harassment, a spike in vandalism, physical assaults. Something is happening that was not happening before,” ADL national director Jonathan Greenblatt told The New Yorker.

Despite those findings, Trump insisted on CBS’ “60 Minutes” the Sunday after his election that there had only been “a very small amount” of racist incidents.

“I am so saddened to hear that,” Trump said when asked about the racist incidents. “And I say, ‘Stop it.’ If it helps, I will say this, and I will say right to the camera: ‘Stop it.’”

He also accused the media of overstating the attacks.

“I think it’s built up by the press because, frankly, they’ll take every single little incident that they can find in this country, which could’ve been there before ― if I weren’t even around doing this ― and they’ll make it into an event, because that’s the way the press is,” he said.

Trump’s denouncement of hate-fueled violence was relatively mild, especially compared to the zeal with which he routinely attacks other targets ― like, say, “Saturday Night Live,” or the cast of “Hamilton,” who addressed Vice President-elect Mike Pence at a recent performance in New York that Pence attended.

“[Trump] hits the news media when he thinks there’s a story that’s unfair, he tweets when he is outraged about something in the media,” CNN host Wolf Blitzer said in November 2016, after Trump criticized the cast of “Hamilton” for singling out Pence, whom the audience also booed. “But he doesn’t seem to go out of the way to express his outrage over people hailing him with Nazi salutes.”

He launched a travel ban targeting Muslims

In an executive order since blocked by the courts, Trump restricted Syrian refugees and travel by immigrants from seven Muslim-majority countries.

While White House press secretary Sean Spicer later insisted that it was “not a Muslim ban,” Trump said the day he signed it that he would prioritize helping Syrian Christians and made an exception for admitting refugees who are religious minorities in those countries.

Trump has characterized people from that region of the world as being “terror-prone,” despite there having been zero fatal terrorist attacks on U.S. soil since 1975 by immigrants from the seven targeted countries: Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria and Yemen.

A blanket ban on travel from those countries and anti-Muslim bigotry in general is “essentially an extension of the fear and vilification of not only Muslims but everyone perceived to be Muslim that’s been taking place for centuries,” Khaled Beydoun, a law professor at the University of Detroit who also works with the Islamophobia Research and Documentation Project at the University of California, Berkeley, explained to Vox.

He attacked Muslim Gold Star parents

Trump’s retaliation against the parents of a Muslim U.S. Army officer who died while serving in the Iraq War was a low point in a campaign full of hateful rhetoric.

Khizr Khan, the father of the late Army Captain Humayun Khan, spoke out against Trump’s bigoted rhetoric and disregard for civil liberties at the Democratic National Convention on July 28. It became the most memorable moment of the convention.

“Let me ask you, have you even read the U.S. Constitution?” Khan asked Trump before pulling a copy of the document from his jacket pocket and holding it up. “I will gladly lend you my copy.”

Khan’s wife, Ghazala, who wears a head scarf, stood at his side during the speech but did not speak.

In response to the devastating speech, Trump seized on Ghazala Khan’s silence to imply that she was forbidden from speaking due to the couple’s Islamic faith.

“If you look at his wife, she was standing there. She had nothing to say. She probably, maybe she wasn’t allowed to have anything to say. You tell me,” Trump said in an interview with ABC News that first appeared on July 30.

Ghazala Khan explained in an op-ed in The Washington Post the following day that she could not speak because of her grief.

“Walking onto the convention stage, with a huge picture of my son behind me, I could hardly control myself. What mother could?” she wrote. “Donald Trump has children whom he loves. Does he really need to wonder why I did not speak?”

He claimed a judge was biased because “he’s a Mexican”

In May 2016, Trump implied that Gonzalo Curiel, the federal judge presiding over a class action suit against the for-profit Trump University, could not fairly hear the case because of his Mexican heritage.

“He’s a Mexican,” Trump told CNN. “We’re building a wall between here and Mexico. The answer is, he is giving us very unfair rulings — rulings that people can’t even believe.”

Curiel, it should be noted, is an American citizen who was born in Indiana. As a prosecutor in the late 1990s, he went after Mexican drug cartels, making him a target for assassination by a Tijuana drug lord.

Even members of Trump’s own party slammed the racist remarks.

“Claiming a person can’t do their job because of their race is sort of like the textbook definition of a racist comment,” House Speaker Paul Ryan (R-Wis.) said, though he clarified that he still endorsed Trump

The comments against Curiel didn’t sit well with the American public either. According to a YouGov poll released in June 2016, 51 percent of those surveyed agreed that Trump’s comments were not only wrong, but also racist. Fifty-seven percent of Americans said Trump was wrong to complain against the judge, while just 20 percent said he was right to do so.

When asked whether he would trust a Muslim judge in light of his proposed restrictions on Muslim immigration, Trump suggested that such a judge might not be fair to him either.

The Justice Department sued his company ― twice ― for not renting to black people

When Trump was serving as the president of his family’s real estate company, the Trump Management Corporation, in 1973, the Justice Department sued the company for alleged racial discrimination against black people looking to rent apartments in the Brooklyn, Queens and Staten Island boroughs of New York City.

The lawsuit charged that the company quoted different rental terms and conditions to black rental candidates than it did to white candidates, and that the company lied to black applicants about apartments not being available. Trump called those accusations “absolutely ridiculous” and sued the Justice Department for $100 million in damages for defamation.

Without admitting wrongdoing, the Trump Management Corporation settled the original lawsuit two years later and promised not to discriminate against black people, Puerto Ricans or other minorities. Trump also agreed to send weekly vacancy lists for his 15,000 apartments to the New York Urban League, a civil rights group, and to allow the NYUL to present qualified applicants for vacancies in certain Trump properties.

Just three years after that, the Justice Department sued the Trump Management Corporation again for allegedly discriminating against black applicants by telling them apartments weren’t available.

In fact, discrimination against black people has been a pattern throughout Trump’s career

Workers at Trump’s casinos in Atlantic City, New Jersey, have accused him of racism over the years. The New Jersey Casino Control Commission fined the Trump Plaza Hotel and Casino $200,000 in 1992 because managers would remove African-American card dealers at the request of a certain big-spending gambler. A state appeals court upheld the fine.

The first-person account of at least one black Trump casino employee in Atlantic City suggests the racist practices were consistent with Trump’s personal behavior toward black workers.

“When Donald and Ivana came to the casino, the bosses would order all the black people off the floor,” Kip Brown, a former employee at Trump’s Castle, told The New Yorker for a 2015 article. “It was the eighties, I was a teen-ager, but I remember it: they put us all in the back.”

Trump allegedly disparaged his black casino employees as “lazy” in vividly bigoted terms, according to a 1991 book by John O’Donnell, a former president of Trump Plaza Hotel and Casino.

“And isn’t it funny. I’ve got black accountants at Trump Castle and Trump Plaza. Black guys counting my money! I hate it,” O’Donnell recalled Trump saying. “The only kind of people I want counting my money are short guys that wear yarmulkes every day.”

“I think the guy is lazy,” Trump said of a black employee, according to O’Donnell. “And it’s probably not his fault because laziness is a trait in blacks. It really is, I believe that. It’s not anything they can control.”

Trump told an interviewer in 1997 that “the stuff O’Donnell wrote about me is probably true,” but in 1999 accused O’Donnell of having fabricated the quotes.

Trump has also faced charges of reneging on commitments to hire black people. In 1996, 20 African-Americans in Indiana sued Trump for failing to honor a promise to hire mostly minority workers for a riverboat casino on Lake Michigan.

He refused to immediately condemn the white supremacists who advocated for him

Trump’s response to the Charlottesville chaos wasn’t the first time he appeared hesitant to condemn white supremacists.

Three times in a row on Feb. 28, 2016, Trump sidestepped opportunities to renounce white nationalist and former KKK leader David Duke, who’d recently told his radio audience that voting for any candidate other than Trump would be “treason to your heritage.”

When asked by CNN’s Jake Tapper if he would condemn Duke and say he didn’t want a vote from him or any other white supremacists, Trump claimed that he didn’t know anything about white supremacists or about Duke himself. When Tapper pressed him twice more, Trump said he couldn’t condemn a group he hadn’t yet researched.

By Feb. 29, Trump was saying that in fact he did disavow Duke, and that the only reason he didn’t do so on CNN was because of a “lousy earpiece.” Video of the exchange, however, shows Trump responding quickly to Tapper’s questions with no apparent difficulty in hearing.

It’s preposterous to think that Trump didn’t know about white supremacist groups or their sometimes violent support of him. Reports of neo-Nazi groups rallying around Trump go back as far as August 2015.

His white supremacist fan club includes The Daily Stormer, a leading neo-Nazi news site; Richard Spencer, director of the National Policy Institute, which aims to promote the “heritage, identity, and future of European people”; Jared Taylor, editor of American Renaissance, a Virginia-based white nationalist magazine; Michael Hill, head of the League of the South, an Alabama-based white supremacist secessionist group; and Brad Griffin, a member of Hill’s League of the South and author of the popular white supremacist blog Hunter Wallace.

A leader of the Virginia KKK who backed Trump told a local TV reporter in May, “The reason a lot of Klan members like Donald Trump is because a lot of what he believes, we believe in.”

Later that month, the Trump campaign announced that one of its California primary delegates was William Johnson, chair of the white nationalist American Freedom Party. The Trump campaign subsequently said his inclusion was a mistake, and Johnson withdrew his name at their request.

After the election, Spencer’s National Policy Institute held a celebratory gathering in Washington, D.C. A video shows many of the white nationalists assembled there doing the Nazi salute after Spencer declared, “Hail Trump, hail our people, hail victory!”

He questioned whether President Barack Obama was born in the United States

Long before calling Mexican immigrants “criminals” and “rapists,” Trump was a leading proponent of “birtherism,” the racist conspiracy theory that President Barack Obama was not born in the United States and is thus an illegitimate president. Trump claimed in 2011 to have sent people to Hawaii to investigate whether Obama was really born there. He insisted at the time that the researchers “cannot believe what they are finding.”

Obama ultimately got the better of Trump, releasing his long-form birth certificate and relentlessly mocking the real estate mogul about it at the White House Correspondents’ Association dinner that year.

But Trump continued to insinuate that the president was not born in the country.

“I don’t know where he was born,” Trump said in a speech at the Conservative Political Action Conference in February 2015. (Again, for the record: Obama was born in Hawaii.)

In September, under pressure to clarify his position, Trump finally acknowledged that Obama was indeed born in the United States. But he falsely tried to blame Hillary Clinton for starting the rumors ― and tried to take credit for settling them himself with his racist pressure campaign.

“Hillary Clinton and her campaign of 2008 started the birther controversy,” Trump said. “I finished it.”

He treats racial groups as monoliths

Like many racial instigators, Trump often answers accusations of bigotry by loudly protesting that he actually loves the group in question. But that’s just as uncomfortable to hear, because he’s still treating all the members of the group ― all the individual human beings ― as essentially the same and interchangeable. Language is telling, here: Virtually every time Trump mentions a minority group, he uses the definite article the, as in “the Hispanics,” “the Muslims” and “the blacks.”

“The Hispanics are going to get those jobs, and they’re going to love Trump.”

- Donald Trump, July 2015

In that sense, Trump’s defensive explanations are of a piece with his slander of minorities. Both rely on essentializing racial and ethnic groups, blurring them into simple, monolithic entities, instead of acknowledging that there’s as much variety among Muslims and Latinos and black people as there is among white people.

How did Trump respond to the outrage last year that followed his characterization of Mexican immigrants as criminals and rapists?

“I’ll take jobs back from China, I’ll take jobs back from Japan,” Trump said during his visit to the U.S.-Mexico border in July 2015. “The Hispanics are going to get those jobs, and they’re going to love Trump.”

How did Trump respond to critics of his proposal to ban Muslims from entering the U.S.?

“I’m doing good for the Muslims,” Trump told CNN last December. “Many Muslim friends of mine are in agreement with me. They say, ‘Donald, you brought something up to the fore that is so brilliant and so fantastic.’”

Not long before he called for a blanket ban on Muslims entering the country, Trump was proclaiming his affection for “the Muslims,” disagreeing with rival candidate Ben Carson’s claim in September 2015 that being a Muslim should disqualify someone from running for president.

“I love the Muslims. I think they’re great people,” Trump said then, insisting that he would be willing to name a Muslim to his presidential cabinet.

How did Trump respond to the people who called him out for funding an investigation into whether Obama was born in the United States?

“I have a great relationship with the blacks,” Trump said in April 2011. “I’ve always had a great relationship with the blacks.”

Even when Trump has dropped the definite article “the,” his attempts at praising minority groups he has previously slandered have been offensive.

Look no further than the infamous Cinco de Mayo taco bowl tweet:

Former Republican presidential candidate and Florida Gov. Jeb Bush (R) offered a good summary of everything that was wrong with Trump’s comment.

“It’s like eating a watermelon and saying ‘I love African-Americans,’” Bush quipped.

In an apparent attempt to win favor with black and Latino voters in the final months of the campaign, Trump fell back on his penchant for stereotyping. At the first presidential debate in September, Trump claimed African-Americans and Latinos in cities were “living in hell” due to the violence and poverty in their neighborhoods. The previous month, speaking to an audience of white people, Trump asked “what the hell do [black voters] have to lose” by voting for him.

Trump’s treatment of longtime White House correspondent April Ryan during a February press conference left many wondering if Trump assumes all black people are friends with one another.

When Ryan, a black reporter for the American Urban Radio Networks, asked Trump if he would hold meetings with members of the Congressional Black Caucus to help craft his urban development policy, he asked her to handle the introduction.

“Well, I would. I’ll tell you what, do you want to set up the meeting?” Trump asked. “Do you want to set up the meeting? Are they friends of yours?”

“No, I’m just a reporter,” Ryan replied.

He trashed Native Americans, too

In 1993, Trump wanted to open a casino in Bridgeport, Connecticut, that would compete with one owned by the Mashantucket Pequot Nation, a local Native American tribe. He told the House subcommittee on Native American Affairs that the Pequots “don’t look like Indians to me... They don’t look like Indians to Indians.”

Trump then elaborated on those remarks, which were unearthed last year in the Hartford Courant, by claiming ― with no evidence ― that the mafia had infiltrated Native American casinos.

He also had no problem using a Native American slur to attack his political rivals.

Just days after proclaiming November as Native American Heritage Month, Trump went after Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.), who has identified as part Native American, with a nickname he’s used against her before: “Pocahontas.”

Invoking Pocahontas, an Algonquin woman associated with an English colony in Virginia, to lodge an attack is unacceptable, Indian Country columnist Ruth Hopkins tweeted.

“Pocahontas was prepubescent girl held hostage & raped by European invaders,” she tweeted after Trump’s remarks earlier this month. “Stop mocking her & Native women.”

Later in November, Trump came under fire for using the slur at an event honoring Native Americans.

“You were here long before any of us were here,” Trump told the honored Native American code talkers who served during World War II. “Although we have a representative in Congress who they say was here a long time ago. They call her Pocahontas.”

Several Democrat lawmakers denounced Trump’s language, and Jefferson Keel, president of The National Congress of American Indians, said Trump’s use of the name as an insult was a distraction from the honorees.

“We regret that the President’s use of the name Pocahontas as a slur to insult a political adversary is overshadowing the true purpose of today’s White House ceremony,” he said in a statement that day.

He encouraged the mob anger that resulted in the wrongful imprisonment of the Central Park Five

In 1989, Trump took out full-page ads in four New York City-area newspapers calling for the return of the death penalty in New York and the expansion of police authority in response to the infamous case of a woman who was beaten and raped while jogging in Manhattan’s Central Park.

“They should be forced to suffer and, when they kill, they should be executed for their crimes,” Trump wrote, referring to the Central Park attackers and other violent criminals. “I want to hate these murderers and I always will.”

The public outrage over the Central Park jogger rape, at a time when the city was struggling with high crime, led to the wrongful conviction of five teenagers of color known as the Central Park Five.

The men’s convictions were overturned in 2002, after they’d already spent years in prison, when DNA evidence showed they did not commit the crime. Today, their case is considered a cautionary tale about a politicized criminal justice process.

Trump, however, still thinks the men are guilty.

He condoned the beating of a Black Lives Matter protester

At a November 2015 campaign rally in Alabama, Trump supporters physically attacked an African-American protester after the man began chanting “Black lives matter.” Video of the incident shows the assailants kicking the man after he has already fallen to the ground.

The following day, Trump implied that the attackers were justified.

“Maybe [the protester] should have been roughed up,” he mused. “It was absolutely disgusting what he was doing.”

Trump’s dismissive attitude toward the protester is part of a larger, troubling pattern of instigating violence toward protesters at campaign events, where people of color have attracted especially vicious hostility.

Trump has also indicated he believes the entire Black Lives Matter movement lacks legitimate policy grievances. He alluded to these views in an interview with The New York Times Magazine where he described Ferguson, Missouri, as one of the most dangerous places in America. The small St. Louis suburb is not even in the top 20 highest-crime municipalities in the country.

He called supporters who beat up a homeless Latino man “passionate”

Trump’s racial incitement has already inspired hate crimes. Two brothers arrested in Boston in August 2015 for beating up a homeless Latino man cited Trump’s anti-immigrant message when explaining why they did it.

“Donald Trump was right ― all these illegals need to be deported,” one of the men reportedly told police officers.

Trump did not even bother to distance himself from them. Instead, he suggested that the men were well-intentioned and had simply gotten carried away.

“I will say that people who are following me are very passionate,” Trump said. “They love this country and they want this country to be great again. They are passionate.”

He stereotyped Jews and shared an anti-Semitic image created by white supremacists

When Trump addressed the Republican Jewish Coalition last December, he tried to relate to the crowd by invoking the stereotype of Jews as talented and cunning businesspeople.

“I’m a negotiator, like you folks,” Trump told the crowd, touting his 1987 book Trump: The Art of the Deal.

“Is there anyone who doesn’t renegotiate deals in this room?” Trump said. “Perhaps more than any room I’ve spoken to.”

Nor was that the most offensive thing Trump told his Jewish audience. He implied that he had little chance of earning the Jewish Republican group’s support, because his fealty could not be bought with campaign donations.

“You’re not going to support me, because I don’t want your money,” he said. “You want to control your own politician.”

Ironically, Trump has many close Jewish family members. His elder daughter Ivanka converted to Judaism in 2009 before marrying the real estate mogul Jared Kushner. Trump and Kushner raise their three children in an observant Jewish home.

In July 2016, Trump tweeted an anti-Semitic image that featured a photo of Hillary Clinton over a backdrop of $100 bills with a six-pointed star next to her face and the label “Most Corrupt Candidate Ever!”

“Crooked Hillary - - Makes History!” Trump wrote in the tweet.

The religious symbol was co-opted by the Nazis during World War II when they forced Jews to sew it onto their clothing. Using the symbol over a pile of money is blatantly anti-Semitic and re-enforces hateful stereotypes of Jewish greed.

But Trump insisted the image was harmless.

“The sheriff’s badge ― which is available under Microsoft’s ‘shapes’ ― fit with the theme of corrupt Hillary and that is why I selected it,” he said in a statement.

Mic, however, discovered that the image was actually created by white supremacists and had appeared on a neo-Nazi forum more than a week before Trump shared it. Additionally, a watermark on the image led to a Twitter account that regularly tweeted racist and sexist political memes.

He treats African-American supporters as tokens to dispel the idea he is racist

At a campaign appearance in California in June 2016, Trump boasted that he had a black supporter in the crowd, saying, “Look at my African-American over here.”

“Look at him,” Trump continued. “Are you the greatest?”

Trump went on to imply that the media conceals his popularity among black voters by not covering the crowd more attentively.

“We have tremendous African-American support,” he said. “The reason is I’m going to bring jobs back to our country.”

Ultimately, Trump won just 8 percent of the African-American vote, according to the NBC News exit poll.

It may not be surprising that Trump brought so much racial animus into the 2016 election cycle, given his family history. His father, Fred Trump, was a target of folk singer Woody Guthrie’s lyrics after Guthrie lived for two years in a building owned by Trump père: “I suppose / Old Man Trump knows / Just how much / Racial hate / He stirred up / In the bloodpot of human hearts.”

And last fall, a news report from 1927 surfaced on the site Boing Boing, revealing that Fred Trump was arrested that year following a KKK riot in Queens. It’s not clear exactly what the elder Trump was doing there or what role he may have played in the riot.

Donald Trump, for his part, has categorically denied (except when he’s ambiguously denied) that anything of the sort ever happened.

He mocks Asian Americans and said he may have supported Japanese internment

According to a report from the Japan Times, the country’s oldest English-language newspaper, Trump said during a visit to Japan in November 2017 that “he could not understand why a country of samurai warriors did not shoot down the missiles” from North Korea.

Setting aside the potentially devastating ramifications of Japan taking steps that North Korea might interpret as an act of war, the “samurai” comment is a reminder that Trump has no problem leaning on stereotypes to make his point.

Back in 2015, Trump spoke in accented, broken English to depict his experience with Asian business partners.

“Negotiating with Japan, negotiating with China, when these people walk into the room, they don’t say, ‘Oh, hello, how’s the weather, so beautiful outside, isn’t it lovely? How are the Yankees doing? Oh they are doing wonderful. Great,’” Trump said at an August 2015 rally in Dubuque, Iowa. “They say, ‘We want deal!’”

But more disturbingly, Trump couldn’t say with certainty that he would have voted against Japanese internment during World War II, stating that war requires making “tough” decisions.

“I would have had to be there at the time to tell you, to give you a proper answer,” he told TIME in a December 2015 interview. “I certainly hate the concept of it. But I would have had to be there at the time to give you a proper answer.”