WASHINGTON -- The shell casings were discovered on the Haven Avenue overpass for Interstate-210 West heading toward Los Angeles. It was dark, but the cops had no trouble finding the brushed aluminum-colored 9 mm husks. Police drew uneven moats of blue or white chalk around the casings and marked each one with a tiny yellow evidence cone. Each cone had a number. There were 48 casings.

The crime scene photos, taken at a distance, show the pinky-sized casings lying zig-zagged in clusters, spreading from the left turning lane, across the double-yellow lines and through one lane and into another. From above, they resemble a school of fish.

The casings served as evidence in the Jan. 18, 2004 murders of Chris Heyman, 17, and Blake Harris, 18, who were shot in the backseat of a tan Mustang in Rancho Cucamonga, Calif. In their last moments, Heyman and Harris talked on their cellphones to friends before they put them down and the driver went to turn the stereo back on. When they reached the overpass, a shooter emptied a modified AP-9 fully-automatic submachine gun in a rapid burst into the Mustang. The gun could fire over 30 rounds per second.

The gunman and his accomplice, out searching for methamphetamine, thought the Mustang had cut them off. During the trial, the accused would admit that he wasn't even sure the tan car was the right one. They exchanged no words with the kids in the Mustang; they were strangers.

The Mustang driver, Michael Universal, who was about a year older than his friends, survived unharmed. With his cellphone out of juice, he had to take one off of one of his friends before he could call for help. "Something happened," he told the 911 dispatcher, according to a transcript. "My back window is shattered." His friends were bleeding from the head, he said. One had "a big lump in his head," and the other was "fucking down," he said. "My best friends," he said. The dispatcher asked if they had been involved in a shooting. Universal wasn't sure.

"You didn't hear a gunshot though?" the dispatcher asked. "I don't know," Universal said. "I was just driving." It happened so fast.

The close-up crime scene pictures show most of the shell casings pinched at the ends, like the plastic tips of cheap convenience-store cigars. The only difference is the number on their evidence markers. Numbers 37 and 40 show blackened gunpowder scars. Numbers 34 and 43 are bullet fragments, jagged-sharp and red tinted.

Note: The images below are graphic and may be disturbing to some readers.

One photo shows a bullet, with a note that says it was taken from the right side of "v/head." It's black as rough coal and almost as big as a plum pit. Bert Heyman, Chris Heyman's dad, had been told that the bullet was pulled from behind his son's right ear.

Just over nine years later, in late February, The Huffington Post interviewed Bert Heyman's wife, Jenny Heyman, for a story on gun violence and trauma. Jenny was heartbreakingly open, sharing her ongoing grief as well as her most cherished memories of her son. But Bert went mute when asked about Chris' death; he would only communicate through email. As he reflected on our email interviews, and the national debate over gun legislation, he said he began thinking of the crime scene, pondering whether to publicize these ghastly police photos of his son's murder.

Heyman had read documentary filmmaker Michael Moore's essay, "America, You Must Not Look Away (How to Finish Off the NRA)." The director of "Bowling for Columbine" argued that the families of the children killed in Newtown, Conn. should release the photos from the crime scene at Sandy Hook Elementary School. Show the American public what an AR-15 does to 6-year-old bodies and the National Rifle Association's reign would be over, Moore argued.

Moore referenced Emmett Till, the 14-year-old African-American boy savagely disfigured and murdered for allegedly flirting with a white woman in Mississippi, and the open casket at his funeral, as helping to draw support to the civil rights movement. He also referenced the photographs from the My Lai massacre as instrumental in turning the country against the Vietnam War.

"I just wanted the world to see," Moore quotes Till's mother as saying at the time of her son's death. "I just wanted the world to see."

Heyman said he admired Till's mother's bravery and found Moore's essay persuasive. "What he says is true to me," Heyman explained. "It spoke to me."

After reading Moore's piece, Heyman went about tracking down Kent Williams, the deputy district attorney who prosecuted his son's killer. "With the Sandyhook massacre and the Gun Regulation issues before us again, we thought it might be a good time to come out of our shell," Heyman wrote Williams in an email.

Heyman had a lot of respect for Williams and the way he kept him informed about every new development in his son's murder case. Williams had kept his promises and won a conviction. To Williams, Chris Heyman's murder stood out, even among the countless gun-violence deaths in California, and the country, each year. California's 4th District Court of Appeal described the killings as "unusually nasty murders."

Even now, when The Huffington Post reached the prosecutor on the phone, Williams circled back to the gun and its prominence in the killer's mind. "There's something about holding a gun that can empty a 50-round clip in seconds," Williams said. "It's like having your finger on a nuclear bomb ... You got the power. You want to use it."

The photos, and the idea of making them public, stirred Heyman into advocacy. Mourning turned into a mission.

"People live not so much in a bubble, but if it's not happening to them they don't really see it or feel it," Heyman said. "People need to see this kind of stuff. They need to feel it."

Heyman's evolution has mirrored much of the country's on gun control. After a string of mass shootings from guns in recent years, many victims and victims' families can no longer sit still as passive grievers. Former Rep. Gabrielle Giffords (D-Ariz.) and her husband, Mark Kelly, formed a political action committee in January aimed at reforming gun laws. The families of Newtown victims have begun actively lobbying Congress. Recently, President Barack Obama gave over his weekly radio address to Francine Wheeler, whose 6-year-old son Ben was killed in Sandy Hook Elementary School. Wheeler didn't just share her grief but updated the country on the Newtown families' lobbying push.

That lobbying took a huge setback last week, when the Senate failed to pass a bipartisan measure that would have expanded background checks and voted down bans on high capacity gun magazines and assault weapons. From the Senate gallery, Patricia Maisch, one of the heroes of the mass shooting in Tucson, shouted, “Shame on you.”

It was legislation that may have prevented deaths like Chris Heyman's. Bert Heyman isn't a politician, nor is he part of a group of families embraced by the rituals of national mourning. He can't get within shouting distance of politicians. He works the swing shift seven days a week at the Miller Brewing Co. plant in Irwindale, Calif. But he said he could feel himself begin to change after HuffPost contacted him in February, and in his subsequent talk with the prosecutor. Heyman had realized he is still very much weighed down by his loss. "We sort of put ourselves in a hole," he said. "To me that was part of my depression, part of me that is scared shitless to stand up in front of people and talk about this kind of stuff. Talking to you just opened that door."

"I really had to re-examine where I was personally," Heyman said. "What's going to help me get out of this rut?"

In the weeks leading up to the murders, the killer had used the gun on another car. Williams believed that the killer had a name for the machine gun. He called it "his Bitch." The gunman had saved the articles about the shooting and the teenagers' deaths. The gunman "wasn't sad about it or anything," a former friend of the shooter testified at the murder trial. "He was pretty much bragging about it."

The jury and the people watching the trial got to see the crime scene pictures. Williams thought the rest of America should see what the "Bitch" could do. He arranged for the photos to be retrieved from storage. It would take several days to find the boxes of 4-by-6 inch prints.

In her book-length rumination on depictions of violence and cruelty in photography, Regarding the Pain of Others, Susan Sontag seemed to settle on the simple idea that citizenship requires that we do not look away. To ignore these violent images is to refuse to be an adult in this world.

It seems a good in itself to acknowledge, to have enlarged, one's sense of how much suffering caused by human wickedness there is in the world we share with others. Someone who is perennially surprised that depravity exists, who continues to feel disillusioned (even incredulous) when confronted with evidence of what humans are capable of inflicting in the way of gruesome, hands-on cruelties upon other humans, has not reached moral or psychological adulthood. No one after a certain age has the right to this kind of innocence, of superficiality, to this degree of ignorance, or amnesia. ... Let the atrocious images haunt us.

Moore, in an interview with The Huffington Post, referenced the Iraq War and President George W. Bush's refusal to allow images of flag-draped coffins coming off military planes as a heinous act of cowardice. Such censorship enables emotional distance, Moore said. "We don't have to take responsibility [for our actions]," Moore said. "We don't have to pay for them … It disconnects us from the rest of the world."

Nearby villagers see the horrors of a drone strike. We have to search images on Google to see the bloody, dusty aftermath. Gun violence in the U.S. gets reduced to a series of crime briefs -- if it's covered at all. "I think we're doing ourselves great personal and societal harm by turning away, by turning our heads away," Moore said.

He noted that Newtown families are not outraged by what he wrote in the essay Heyman read. Some, Moore said, have contacted him and have been encouraging, but he wouldn't reveal more about their conversations.

If Newtown photos come to light, Moore insisted it would have to be with the parents' consent. "I know it would be very difficult because you would want your child to be remembered as a sweet, beautiful child," he said. "But it begs the question of do people really get that Adam Lanza only needed one shot to the heads of these kids to kill them and then … fired up to another 10 shots in each of them, riddling their bodies with these high-powered bullets from an assault rifle at close range?"

Moore wondered how many Newtown parents could only identify their children by the clothes that they were wearing that day.

For Heyman, the public doesn't have to know all that Chris was. But they have to know the impact that these weapons can have on a body. It isn't just about his son in those pictures. "It could be anybody," he said.

After the shooting, Michael Universal sped off in the Mustang with his two friends fatally wounded in the backseat. He took refuge in a nearby McDonald's parking lot. The photos show that he pulled in to a spot facing the fast-food chain's bright enclosed playground for children. The entire area would soon be cordoned off with yellow police tape.

Some cops are shown standing around. Others sit inside a police van.

On the ground a few feet from Chris Heyman's body and the Mustang, there is a torn seat belt purple with blood. Nearby, there is a Burger King soda cup. It was photographed and marked. Next to the back wheel is Chris Heyman's friend's black track clothes and black sneakers, still laced all the way to the top. Where there is white, you can see blood spray.

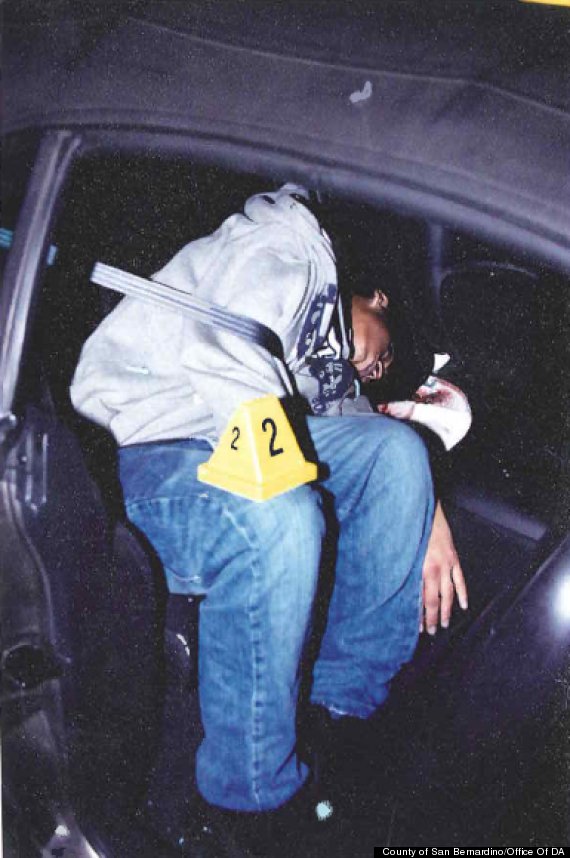

A passenger side door is open, revealing a foot and then an ankle. A bloody hand hangs to the side, Chris' bloody hand. He is still in his seat, his torso and head are slumped over out of view. The eye is drawn to Chris' knee, tagged with evidence marker No. 2. His body is now evidence: Not something to love, but something to work.

"That's my boy," Heyman recalled thinking. He had come to pick up the pictures from Williams, but the prosecutor wanted to review the photos with him first. They sat in a conference room, with Williams placing the photos on the table. "That's my boy laying there." He said he felt his own body drain of energy.

The mortuary had been willing to have an open casket. But Jenny Heyman didn't want to see her son that way. Instead, Bert Heyman had a small private viewing at "a real old creepy church" the night before the funeral.

"We had to put a hat over his head," the father recalled. "You could see his face." He stopped for a moment and began to sob. "Sorry, man," he said. "There were just pieces of his head missing."

Jenny Heyman told me she has not seen the photos and had no plans to do so. At the trial, as evidence of Chris Heyman's wounds was being presented, she walked out of the courtroom. When she has thought about her son's murder, she said, the effect is physical. "I can feel the bullets hitting me," she said. "I can actually feel the bullets hitting me."

"You have to understand, I'm the mom," she said. "I'm supposed to be there to protect him that night and I couldn't do that."

After much thought, Jenny Heyman decided to support her husband and allow the photos to be released. Bert told her he felt like this is the last way they can honor Chris. "I think it's the right decision to do this. It's just taken me a little longer to understand it. It just hurts," she said.

It's up to us to look.

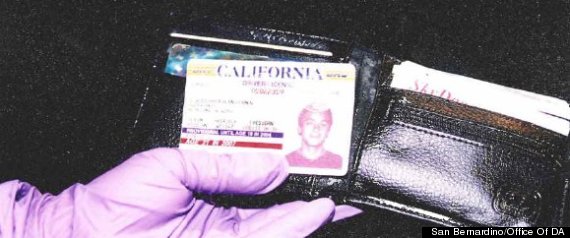

In one photo, a crime scene technician wearing protective purple surgical gloves takes Chris' wallet from his body and photographs his California driver's license, which reads provisional until age 18. The license lists his hair as black and his eyes as brown. He weighed 147 pounds. He was an athletic kid at home on a soccer field and was taking lessons to pilot an airplane. Staring out from his driver's license photo, his smile looks blissful.

Inside the car, that life is gone. The submachine gun's bullets made parts of his head disappear. Blood spills into a towel and smears across his forehead and into his eyes. The blood sticks over his eyes and across the bridge of his nose like a mask. Chris is still wearing his seatbelt.

His right temple is a purple-metallic color. Blood is trailing from his ear. On his neck above his collar bone, there's a quarter-size bullet wound on his neck. Blood streaks from the hole across his neck. Chris' mouth is slightly open. His eyes are closed. His face is gray and slack.

Bert Heyman stopped at these pictures and couldn't look any more.

"I'm living it," he said. "I don't need to see the pictures."

Throughout the debate, Republicans have engaged warily with victims of gun violence, by turns expressing sympathy and dismissing them as "props" sent out to exploit the emotions of lawmakers. On Wednesday, after the critical amendments failed, Obama reacted angrily to the treatment of the victims. "Do we really think that thousands of families whose lives have been shattered by gun violence don't have a right to weigh in on this issue?" Obama said. "Do we think their emotions, their loss is not relevant to this debate?"

A couple of days before the Senate defeats, Heyman began to sense that whatever he was doing to publicize his son's tragic death would be futile. He emailed a 700-word essay he wrote called "Parent to Parent Plea" which calls for gun regulation -- anything that might prevent a tragedy like the one he endured. Out of his bottomless grief now came this endless energy, he says, that inspired these words.

"We have an opportunity to change our mindset," Bert concluded. "We can be proactive and plan ahead, when you see that we average upwards of 30,000 gun related deaths here in the United States of America every year. It's time for us to pull together as in 'We the People' and think about next year's 30,000 gun deaths and do something positive to try and break that trend … Think of the Victims Families that are left behind, to grieve, to struggle, to wonder ..."

I asked Bert why he wrote it.

"Maybe the pictures aren't enough," he said.