TOKYO -- President Obama recited the American credo "that all men are created equal" in his Dec. 9 speech on race relations to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the 13th Amendment.

His speech had the gravity that only he, the first African American president, could render. It also had implications for, and has been interpreted in the context of, the current political debate on a proposal to deny immigration to certain foreigners based on their religious affiliation.

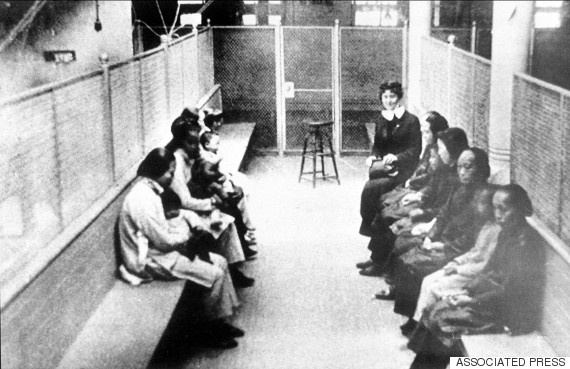

The current debate reminds Japanese people of an unfortunate episode in American history that undermined relations between the countries. In the early 1900s, sentiments against Japanese immigrants in the Western regions of the U.S. gradually rose and eventually turned virulent.

Continued efforts to defuse the situation through diplomacy, such as relying on voluntary restriction of emigration enforced by the Japanese government, ended in 1924 when the U.S. Congress passed the Immigration Act, which effectively denied immigration from Japan.

The immigration system that discriminated against the Japanese based solely on their race was a public humiliation for them that had serious consequences on the ties between the two nations. What transpired between Japan and the U.S. during the 1930s and the 40s, namely the rupture and the subsequent war, was nothing but a great tragedy. Although the immigration ban was only one of many factors that contributed to the two decades of our most difficult history, it cannot be dismissed as insignificant.

The United States may repeat policies that many regard as a blight on its history.

Fortunately, the two countries have put this tragic history behind them and are now close friends and strong allies based on their shared beliefs in respect for basic human rights, liberal democracy and the rule of law.

After the war, Japan transformed itself into a fully liberal and representative democracy. Around the same time, attitudes in the United States on racial, ethnic and religious discrimination were evolving to reflect the rise of postwar liberal progressivism. This evolution resulted in The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952, which repealed eligibility qualifications in the prewar legislation that discriminated against certain racial and ethnic groups, and the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, which discontinued race and ethnic based immigration quotas.

While the discriminatory provisions have been relegated to history, it is instructive to revisit the immigration act of almost 100 years ago and the jurisprudence, especially the Supreme Court's 1922 decision in Takao Ozawa v. United States, which provided the legal basis for the Immigration Act and has never been overruled.

Mr. Ozawa was a Japanese national living in the United States whose application for citizenship was denied in October 1914. When his appeal reached the Supreme Court in 1922, the court affirmed the denial on the ground that Mr. Ozawa not "of the Caucasian race" and thus not "white" within the meaning of the Naturalization Act of 1790, as amended by an act of 1870, which limited citizenship "to aliens being free white persons, and to aliens of African nativity and to persons of African descent."

In an earlier decision upholding the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the court had held that Congress had a plenary power with respect to matters of naturalization and immigration. The plenary power doctrine, which permits discrimination based on race, was the legal basis for the 1924 immigration act.

Although old laws like the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and the Immigration Act of 1924 are no longer on the books, some commentators claim that the plenary power doctrine is still good law. If this is correct, then Congress may, without fear of judicial review, discriminate based on race, religion or any other ground that it deems appropriate when it determines who may, or may not, immigrate to, or become a citizen of, the United States.

The United States, like any other country, needs broad control over who can enter -- and remain in -- its borders and who can become a citizen. Noncitizens who want to immigrate to, or visit, the United States cannot expect to benefit from all of the rights that citizens of the United States enjoy.

However, if the plenary power doctrine gives Congress a power with respect to immigration and naturalization that is never subject to judicial review, then there is risk that the passions and prejudices of the moment will result in laws that make a mockery of America's founding ideal "that all men are created equal."

President Obama's speech suggests that there should be an interpretation of the Constitution that reconciles Congress' need for a broad power over immigration and naturalization and the risks associated with judicial intervention in the exercise of that power with the need to prevent blatantly discriminatory laws that are a public humiliation to those they discriminate against. Without that interpretation, the United States may repeat policies that many regard as a blight on its history.

Acknowledgement with appreciation for the advice and encouragement from Mr. Joshua T. Rabinowitz, a retired lawyer (Harvard JD) is in order, but any mistakes or shortcomings are solely the writer's responsibility.

Also on WorldPost: