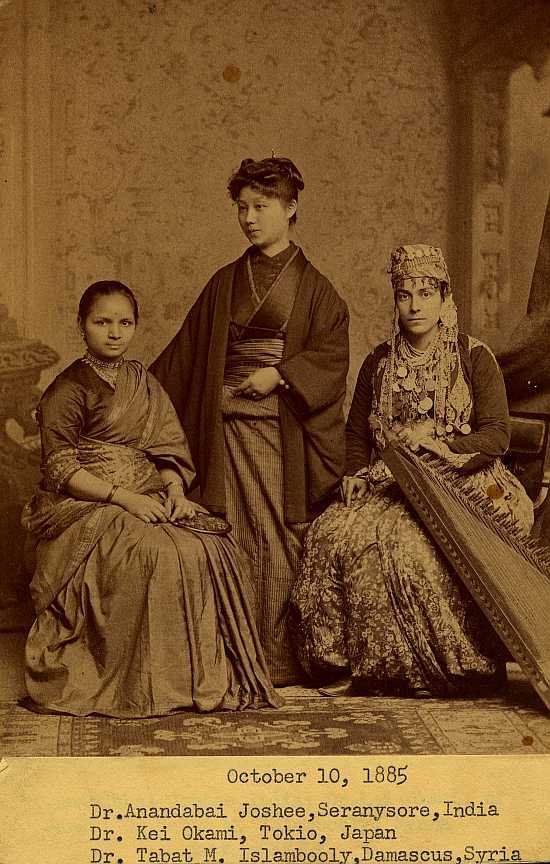

Every so often, the same mysterious image seems to pop up on the internet. The black-and-white portrait looks to be at least a hundred years old, and yet, it is of an Indian woman, a Japanese woman and a Syrian woman, sitting in Pennsylvania.

From the Drexel University College of Medicine Archives and Special Collections.

The image -- doing rounds this time thanks to Jaipreet Virdi-Dhesi, a Ph.D. student who uploaded the photograph to her blog, having stumbled on it while researching 19th century ear surgery in the Drexel University College of Medicine online archives -- is remarkable enough to warrant the fuss. The three magnificently dressed ladies were students at the Women’s Medical College of Pennsylvania, snapped at a Dean’s reception, in 1885.

If the timing doesn't seem quite right, that's understandable. In 1885, women in the U.S. still couldn't vote, nor were they encouraged to learn very much. Popular wisdom decreed that studying was a threat to motherhood. Women who went to college, wrote the Harvard gynecologist Edward H. Clarke in 1873, risked “neuralgia, uterine disease, hysteria, and other derangements of the nervous system,” such as infertility. “Because,” went Clarke's reasoning, in a classic bit of mansplaining titled "Sex In Education," a woman’s “system never does two things well at the same time.”

So how did our seemingly non-hysterical trio wind up inside a medical school? And that too, from thousands of miles away?

In a report last year for PRI’s The World on the image -- which seems to go viral annually -- Christopher Woolf credits unsung heroes for making the situation possible: the Quakers, “who believed in women’s rights enough to set up the WMCP way back in 1850 in Germantown.”

"It’s a reminder just how exceptional America was in the 19th century," Woolf writes. "We often spend so much time remembering all the legitimately bad things in U.S. history. But compared to the rest of the world, America was this inspirational beacon of freedom and equality."

The first women’s medical college in the world, the WMCP was a magnet for ambitious ladies of all stripes. The three in the photograph -- from left to right, Anandibai Joshi, Keiko Okami, and Sabat Islambouli -- eventually became among the first licensed female doctors in their respective countries: India, Japan and Syria.

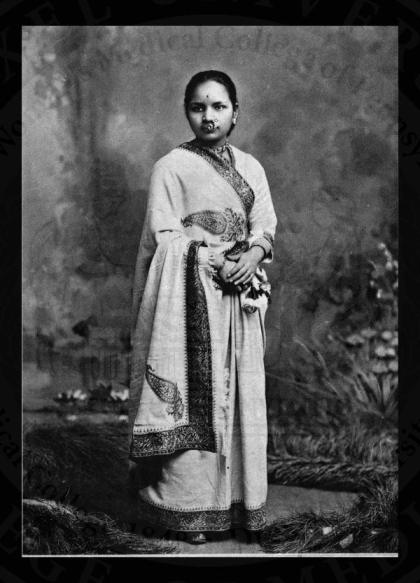

A close-up of Anandibai Joshi, one of three early foreign graduates of the WMCP.

Joshi is the best known of the three, perhaps because of how popular the medical profession is among Indians and Indian Americans. In India, Joshi's life story became the basis for a 1992 novel and subsequent award-winning play (and was nearly turned into a movie). In America, the feminist Caroline Healey Dall wrote a biography of the young doctor as early as 1888, full of praise for Joshi’s “high-born consciousness.”

You can understand the fascination. On paper, Joshi's life seems hugely regressive, but in reality it was anything but. She was married off at the age of nine, to a 20-year-old man. Unusually, he believed fervently that she should be educated, and took her lessons on himself.

According to Woolf’s report, what impelled Joshi to pursue medicine was the death of her 10-day old baby, a tragedy that struck when she was herself only 14. As she learned, and as Woolf points out, “medical care for women -- even high-caste women like Joshi -- was simply unavailable.”

Partly this was an issue of social norms, of women feeling incapable of getting gynecological service from men. In her application letter, excerpted in part at the PRI site, Joshi sells herself as the first step to a solution. Her purpose, she writes, is to return to India that she might "render to my poor suffering country women the true medical aid they so sadly stand in need of and which they would rather die than accept at the hands of a male physician." (The full excerpt is a masterful example of the self-sale, and worth a read.)

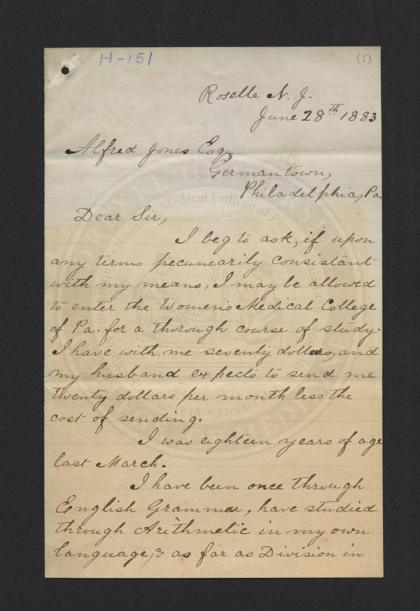

Another fragment of a letter Joshi wrote to an executive of the WMCP, asking for admission to the college, and financial assistance.

She was well-read, thanks in part to her husband, but not wealthy enough to actually travel to the U.S. and attend medical school. The Oxford Encyclopedia of Women in World History details the circuitous route the couple took to find a backer to send Joshi to America. Fittingly, it was a woman who stepped in: Theodicia Carpenter, a wealthy New Jerseyite who read of the couple in a local Christian paper, after they turned down an offer from an American missionary who promised funds only if they converted from Hinduism to Christianity.

Woolf details the hardships Joshi faced even after getting licensed. According to a Drexel archivist he spoke with, India's first female physician died of tuberculosis at 21, too young to ever practice. As for the other two women in the internet's favorite 19th century graduation picture, life wasn't simple going for them either: Islambouli fell off the university’s radar after moving home, an indication that she likely dropped her career. Okami went on to become head of gynecology at a top Tokyo hospital, only to resign when the reigning emperor refused to meet her during a visit to the hospital, because she was a woman.

The WMCP graduates are the ones we remember though, and for good reason: in a few years, women doctors are poised to outnumber men around the world.

CORRECTION: A previous version of this story relied on the PRI report's identification of the photograph's three women as "the first" licensed female physicians out of each of their countries. Drexel archivist Matthew Herbison tells HuffPost that this title isn't accurate. At least in the case of Keiko Okami, another Japanese woman, Ogino Ginko, "appears to have been the first...to receive her degree." As for the other two women, Herbison points out that record-keeping is by nature a malleable science, and so we can't ever definitively know who was "first." The change has been noted in the text.