Last month, a San Francisco tour guide was caught in a racist rant about the city's Chinatown, berating residents for "eating turtles and frogs" and for not assimilating into American culture.

Last month, a San Francisco tour guide was caught in a racist rant about the city's Chinatown, berating residents for "eating turtles and frogs" and for not assimilating into American culture.

There's an irony to these grievances, considering that Chinatowns in the U.S. sprang up in large part because of anti-Chinese racism, and because of legal barriers that prevented assimilation.

At their height, there were dozens of Chinatowns, in big metro areas like Los Angeles and Chicago and in smaller cities like Cleveland and Oklahoma City. You might think of these neighborhoods as places to eat dim sum and buy knickknacks, but the reasons they initially formed are much more complex -- and political.

Chinatown, San Francisco, late 19th century.

Chinese immigrants congregated together in part because of intense anti-Chinese attacks.

Seeking economic opportunity during the Gold Rush and the building of the transcontinental railroad, the first wave of Chinese immigrants arrived in the U.S. in the mid-1800s. The first Chinatowns sprang up on the West Coast and were, at the start, much like ethnic settlements founded by European immigrant groups.

These immigrants were paid lower wages than white workers, who then blamed Chinese laborers for driving down pay and taking away jobs. After the railroad was completed and white laborers in other industries began to fear for their jobs, anti-Chinese attacks increased, including beatings, arson and murder.

In Rock Springs, Wyoming, 150 armed white miners drove Chinese immigrants out of town in 1885 by setting fire to their homes and businesses and murdering 28 people. No one was charged in the massacre. It was hardly an isolated incident; 153 anti-Chinese riots erupted throughout the American West in the 1870s and 1880s, with some of the worst episodes of violence in Denver, Los Angeles, Seattle and Tacoma, Washington.

Many Chinese immigrants moved east to escape the attacks, explains Beatrice Chen, public programs director for the Museum of Chinese in America, located in New York. "That's really how Chinatowns on the East Coast got their start," she tells HuffPost. At the same time, Chinese immigrants who remained on the West Coast sought safety in numbers in the Chinatowns there.

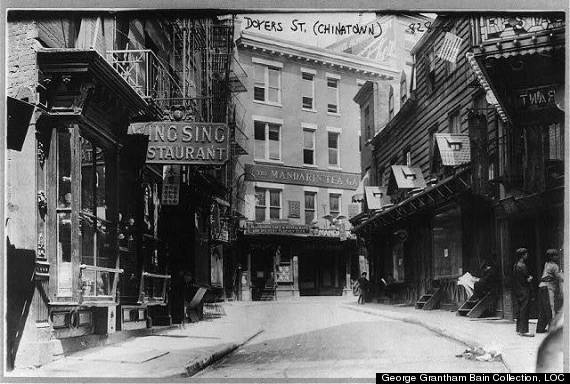

Doyers Street in New York City Chinatown, 1909.

The Exclusion Act of 1882 created significant legal barriers to Chinese immigrants’ assimilation.

Around the turn of the century, politicians played into white workers' anxieties, pointing the finger at Chinese immigrants for economic hardship and labeling them fundamentally incapable of assimilation into U.S. society.

In 1877, a congressional committee heard testimony that the Chinese "are a perpetual, unchanging, and unchangeable alien element that can never become homogenous; that their civilization is demoralizing and degrading to our people; that they degrade and dishonor labor; and they can never become citizens."

Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, barring Chinese immigrants who were already in the U.S. from becoming citizens and restricting new immigration from China. The law marked the first time that the U.S. restricted immigration explicitly on the basis of race.

Along with the Exclusion Act's renewal in 1892, Congress required all Chinese-Americans -- including U.S.-born citizens -- to carry photo ID at all times or risk arrest and deportation.

In response to exclusion, community organizations in Chinatown provided services to immigrants who weren't protected by the benefits of American citizenship. “I think of them as sort of the first social service agencies for the Chinese," Chen says. "That's why you see a lot of informal networks and associations within Chinatowns in the United States."

In San Francisco's Chinatown, for example, The Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association provided legal representation, organized a private watchmen patrol for the neighborhood and offered health services.

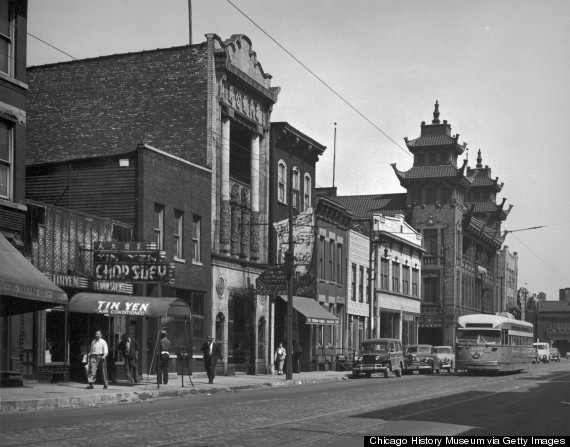

Looking north, with a view of the Pui Tak Center building (far right) on Wentworth Avenue in Chicago's Chinatown neighborhood, ca 1940s.

Housing and labor discrimination kept Chinese immigrants from being able to live and work outside of Chinatown.

During the exclusion era, it was difficult for Chinese immigrants to find a place to live outside of Chinatown. "In the broadest strokes, Chinatowns were products of extreme forms of racial segregation," explains Ellen D. Wu, a history professor at Indiana University Bloomington and author of The Color Of Success: Asian Americans And The Origins Of The Model Minority. "Beginning in the late 19th century and really through the 1940s and '50s, there was what we can call a regime of Asian exclusion: a web of laws and social practices and ideas designed to shut out Asians completely from American life."

"That's really how Chinatowns came into being," Wu adds, "not how we think about them now, as a fun place to get a meal or buy some tchotchkes, but as a way to contain a very threatening population in American life."

Several Western states passed laws that prohibited Chinese immigrants from owning property. In Manhattan's Chinatown, Chen says, some Italian immigrants sold buildings to the Chinese, but it was difficult to find white landlords who would sell to them on other parts of the island.

Chinese immigrants also were barred from most industries, aside from the hand-laundry and restaurant businesses. "It strengthened Chinatown that whites basically refused to work with the Chinese," says Peter Kwong, a professor of Urban Affairs and Planning at Hunter College in New York. "Chinese immigrants had to find work through self-employment."

"The street of the gamblers" in San Francisco Chinatown, around the turn of the 20th century.

Before World War II, Chinatowns were stereotyped as disgusting dens of iniquity.

Because of the Exclusion Act, male laborers who came to the U.S. to work on the railroad could not be reunited with their families back in China. As a result, Chinatowns before World War II were disproportionately populated by men. They were viewed by white Americans as "depraved colonies of prostitutes, gamblers and opium addicts bereft of decency," Wu wrote in a Los Angeles Times op-ed earlier this year.

In 1885, San Franscisco city government formed a committee to investigate depravity in Chinatown. The report is full of moral panic about crime, poor sanitation, and "white women living and cohabitating with Chinamen."

"Your Committee were at that time impressed with the fact that the general aspect of the streets and habitations was filthy in the extreme, and so long as they remained in that condition, so long would they stand as a constant menace to the welfare of society as a slumbering pest, likely to generate and spread disease should the city be visited by an epidemic in any virulent form," the report reads. "Your Committee are still of the opinion that it constitutes a continued source of danger of this character, and probably always will, so long as it is inhabited by people of the Mongolian race."

Another passage whips up anxiety about Chinatown as a kind of lawless zone. "Not only does the cunning and utter unscrupulousness of Chinamen enable them to evade our laws," the committee writes, "but the evidence is conclusive that they have well organized tribunals of their own which punish offenders against themselves when it is in their interest to punish, but which never punish those who violate the laws of the city or the State."

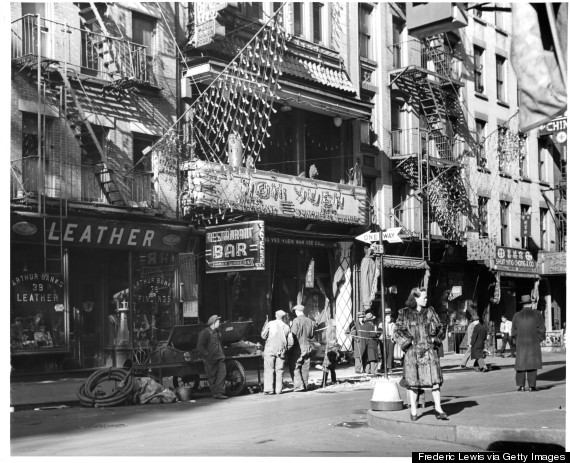

Bars, shops, and apartments in Chinatown, San Francisico, 1955.

Opponents of the Exclusion Act tried to re-brand Chinatowns as friendly places full of model families.

As the U.S. fought wars abroad in the name of freedom and democracy, Wu says, American liberals became worried that the Exclusion Act would make the country seem hypocritical. At the same time, American leaders felt that the Exclusion Act would complicate the U.S. alliance with China against Japan.

In a bid to repeal the act, Wu says, American writers like Pearl Buck began to tell stories of Chinatowns as places where model families thrived. Although U.S. immigration law greatly restricted the entry of Chinese women, some immigrated as the wives and daughters of merchants and other groups exempted from the Exclusion Act, and families formed.

"The Citizens Committee to Repeal Chinese Exclusion recognized that it would have to neutralize deep-seated fear of 'yellow peril' coolie hordes," Wu writes. "So it strategically recast the Chinese in its promotional materials as law-abiding, peace-loving, courteous people living quietly among us."

The image stuck after the repeal of the Exclusion Act in 1943. As wartime social changes prompted teens to act out and fears about a national juvenile delinquency crisis grew, journalists pointed to Chinese families as a virtuous exception.

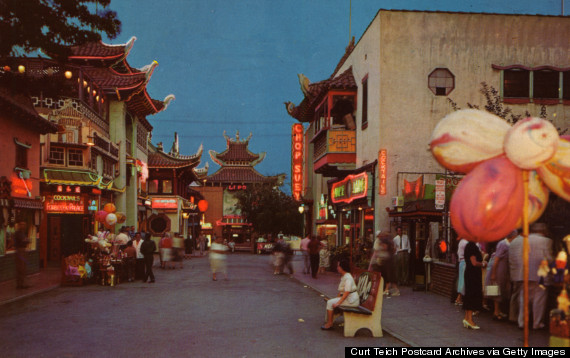

Vintage postcard view of the towers, pagodas and storefronts along Gin Ling Way in Los Angeles Chinatown.

This re-imagining of Chinatowns came against the backdrop of a media-induced panic about young white Americans falling into lives of crime. Fears became so pronounced that the FBI took notice. Director J. Edgar Hoover appeared in newsreels, exhorting American parents to provide moral guidance for their children.

Around the same time, the federal government was staging immigration crackdowns in Chinatowns, fearing that communists were sneaking into the country posing as relatives of U.S. citizens.

Chinatown leaders actively fostered the image of Chinese-Americans as model citizens in the hopes that it would protect them. "In 1956, Chinatown leaders in San Francisco do start to think strategically," Wu says. "They hire some public relations people to figure out how to promote a positive, friendly image of Chinatown. And one of the talking points is, again, really emphasizing this idea of a proto-Tiger Mom and these well-behaved, non-delinquent children."

Journalists for popular publications like Reader's Digest -- in consultation with publicists contracted by Chinese community leaders -- painted Chinese families as a model for solving the delinquency "crisis," Wu explains. "They point to these model households where there's respect for law and order, respect for parents and teachers, where you go to Chinese school and learn about the Confucian world." At the same time, there was juvenile delinquency in Chinatowns -- but the image of the Chinese-American community created in the media left that out. "It was a fiction," Wu says, "but one that was politically useful for the community."

There were also economic benefit to refashioning Chinatown as an agreeable place for tourists. "The San Francisco Chinatown gate was only built in 1970," Wu explains. "Even in some of the promotional literature about why you should visit Chinatown, they say, come visit and see our model families, see our children who never get into trouble and love to study."

Mott Street in Chinatown, New York City, ca 1950.

While Chinatowns were touted as tourist destinations, the garment industry revitalized them as places where people lived and worked.

From the 1970s onward, economic forces primarily contributed to the growth of Chinatowns, Kwong says. As U.S. manufacturing moved increasingly out of urban centers to cheaper factories overseas, garment factories moved into Chinatowns in cities like New York, Boston and Philadelphia to take advantage of the low rents and cheap labor.

City University of New York Professor Kenneth J. Guest wrote of New York's Chinatown:

Until the 1960s, the U.S. garment industry primarily employed unionized Italian and Jewish immigrants. But in the 1960s and 1970s, as aging garment workers retired and the bulk of New York's garment manufacturing was relocated overseas, manufacturers increasingly turned to Chinatown's shops filled with young immigrant women workers, to preserve a local base of operations that could respond quickly and cheaply when the overseas supply line was disrupted. In the early 1980s, Chinatown's garment shops employed 20,000 workers.

During this time, more two-income households emerged in America's Chinatowns, Kwong says, with the men working in restaurants while the women worked in the factories.

Garment workers in a Chinatown dress factory.

Today, Chinese immigrants are being pushed out of Chinatowns by gentrification -- but migration persists.

After the garment industry declined in the 1990s and gentrification set in, Chinese immigrants were priced out of old Chinatowns. That trend continues.

"Chinatowns in many parts of the United States are disappearing,” Kwong says. “Many Chinatowns became very desirable real estate, and for a variety of reasons, they disappeared or become simply tourist destinations. San Francisco old Chinatown is pretty much that."

A 2014 report from the Asian American Legal Defense And Education Fund, a civil rights group, criticized local governments in New York, Boston and Philadelphia for promoting rezoning and development projects that accelerated gentrification. "Government policies have changed these traditionally working class, Asian, family household neighborhoods into communities that are now composed of more affluent, White, and non-family households," the authors write.

"Chinatowns are turning into a sanitized ethnic playground for the rich to satisfy their exotic appetite for a dim sum and fortune cookie fix,” Andrew Leong, co-author of the report, tells the BBC.

San Francisco's Chinatown.

But Chinese immigrants are still flocking to Chinatowns in large numbers, fleeing poverty, or religious or political persecution. Since the 1980s, an influx of undocumented immigrants from China's Fujian province has expanded New York's Chinatown eastward.

When a ship named the Golden Venture ran aground off of Queens in 1993, carrying nearly 300 undocumented migrants, it provided a tragic illustration of the extreme lengths people will go to reach American shores.

The informal networks in Chinatown -- some of which draw their lineage from the Exclusion era -- allow undocumented immigrants to get a foothold after arrival. But sometimes they can also keep them stuck there.

"For most Fuzhounese immigrants, Chinatown is the first stop in America," Guest wrote in City Limits magazine in 2003. "Here they connect with family, housing and jobs. But while Chinatown is a gateway, for many Fuzhounese it is also a trap, an ethnic enclave manufactured by the neighborhood's Mandarin- and Cantonese-speaking economic and political elites to keep them isolated and easy to exploit."