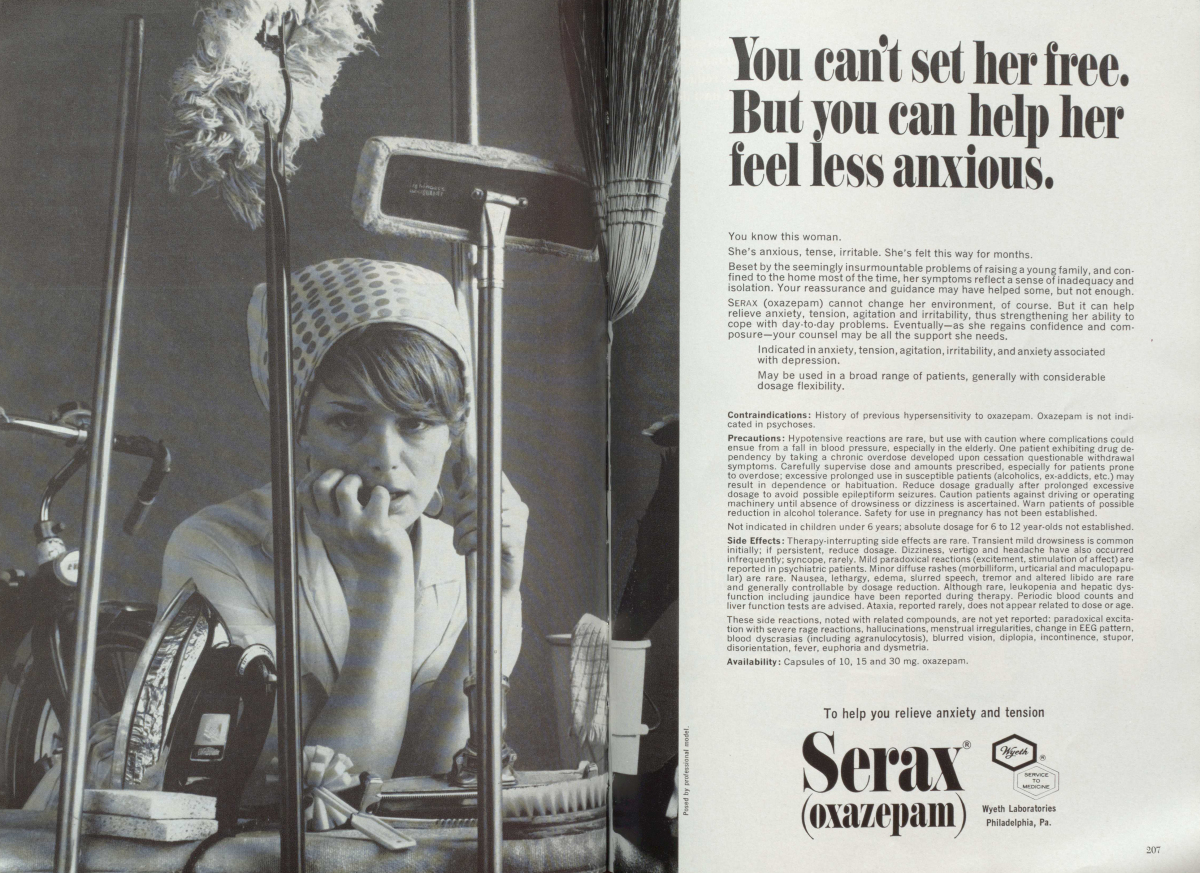

(Photo credit: Serax) Published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, 1967

While vintage advertising usually conjures images of "Mad Men"-era consumer campaigns -- think the iconic "I'd like to buy the world a Coke" commercial from the show's final episode -- print ads for pharmaceutical drugs often skipped the consumer altogether. Drug advertisements peppered the pages of medical journals like the American Journal of Psychiatry and the Journal of the American Medical Association, creating a direct pitch line between the ad men selling Effexor and Valium and the doctors who prescribed anti-depressants to patients.

Eleven percent of Americans over the age of 12 take antidepressants, with 2.5 times as many women taking medication for depression as men, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. But these rates don't accurately represent the state of mental illness in America, according to Jonathan Metzl, professor of sociology and psychiatry and director of the Center for Medicine, Health and Society at Vanderbilt University, who thinks there might be more to these statistics than meets the eye.

"For a long time, depression was presented in ways that were very problematic in American society," Metzl said. "One of the things I found in my research, was that drug ads, and particularly drug ads to doctors, showed almost entirely white women. There was a cultural message that white women were the only people who could afford to be depressed and there was a strong correlation between being married and being mentally healthy," he said.

One in 10 Americans suffers from depression, and for many, anti-depressants are a necessary, and sometimes even lifesaving, treatment. Still, the fact remains that anti-depressants are overprescribed to a remarkable degree. In 2013, a large-scale study published in Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics found that two-thirds of patients given a diagnosis for a major depressive episode in the previous year did not meet the criteria outlined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) for the condition.

One study that Metzl worked on, published in Social Science and Medicine in 2004, examined the way men and women with depressive illness were portrayed in newspapers and magazines between 1985 and 2000. The study found that articles described women who needed SSRI drugs (or selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors, a type of anti-depressant) in non-medical, emotional terms, like being "overwhelmed by sadness" or "feeling down," for example. Men, on the other hand, were more likely to be described using clinical terms from the DSM. They suffered from an illness with "biochemical roots" or had "obsessive compulsive disorder," ads said. In addition, the reasons women were taking SSRI drugs were overwhelmingly tied to marriage, mothering, menstruation and menopause, while reasons given for men to take the drugs were tied to aggression and athletics. In cases where race was identified or assumed, 95 percent of the representations were white people.

Being over-marketed to, or completely ignored by marketers, can have real-life implications. "Cultural representations are incredibly powerful, because they reinforce cultural stereotypes and sometimes they create them," Metzl told The Huffington Post. "For a long time, overrepresentation of white, middle-class women in American media and movies and drug ads led to an overprescription of anti-depressants and anti-anxiety drugs for women and an under-diagnosis for all other kinds of people -- people of color, people who were gay or lesbian, everybody else, basically."

Indeed. Compared to the 16.6 percent of white adults, only 7.6 percent of black adults used mental health services, according to a 2011 SAMHSA survey.

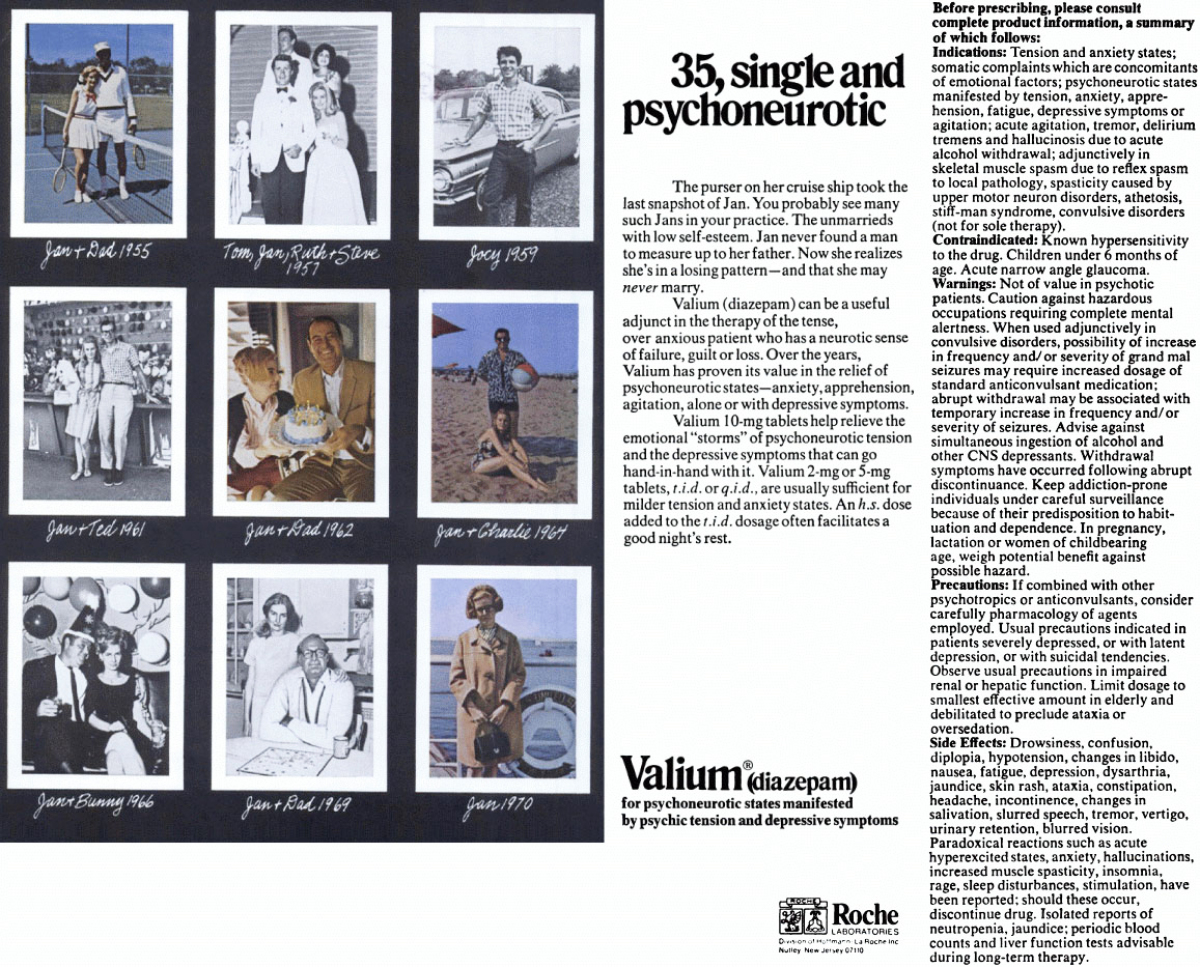

(Photo credit: Valium) Published in Hospital and Community Psychiatry, 1970

The advertisements throughout this story, which appeared in medical journals between 1967 and 2004, play on a variety of cultural stereotypes surrounding womanhood and depression. One advertisement, which appeared in the medical journal Hospital and Community Psychiatry in 1970, pathologizes single women, prompting doctors to prescribe Valium to women like "Jan," a 35-year-old who "never found a man to measure up to her father."

Early on, stereotypically unhappy, single women made the rounds in advertising. "Pharmaceutical ads in medical journals for about 40 or 50 years, very often showed depressed, untreated women without wedding rings," Metz said. "What they would do then, is show mentally health women who had wedding rings and who were happily married."

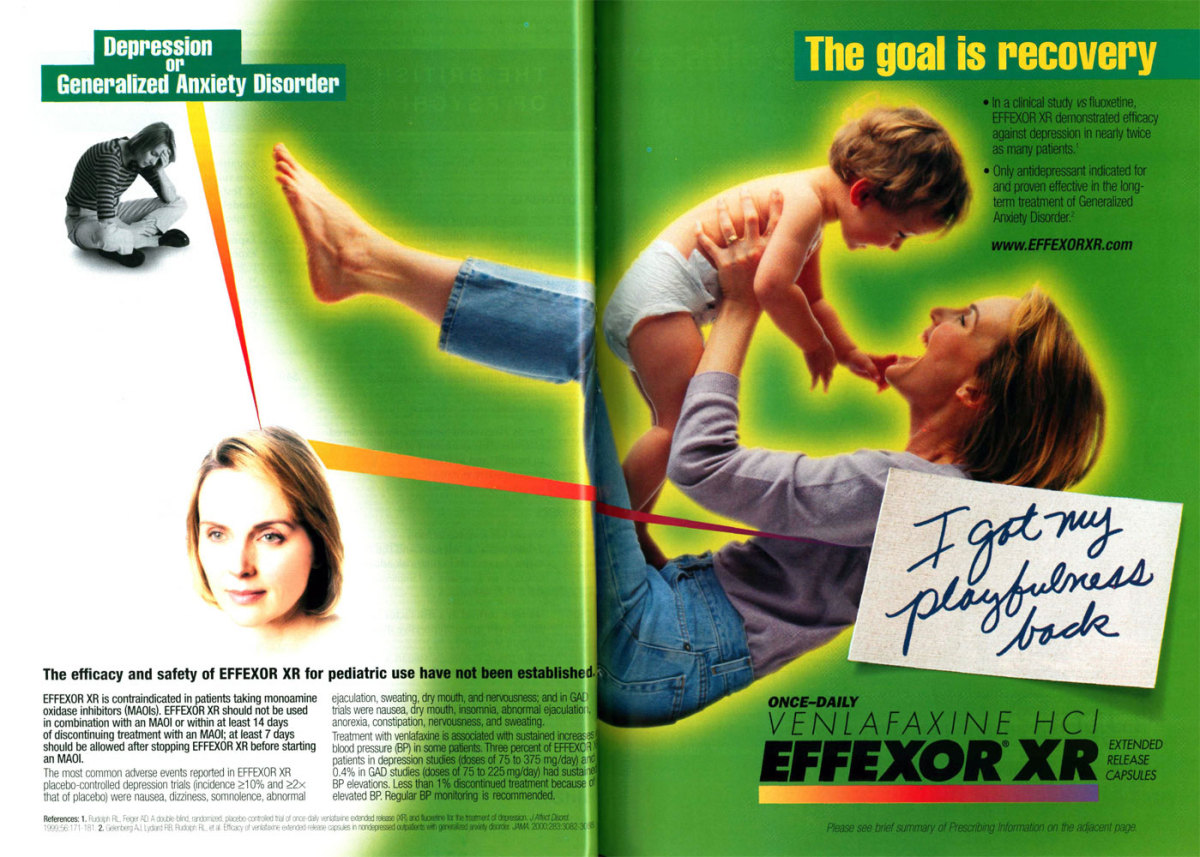

Other ads medicalized motherhood. One ad for the anti-depressant Effexor, published in the American Journal of Psychiatry in 2001, depicts a woman in black and white, sitting hunched over with her hand on her head, beneath the words "depression or generalized anxiety disorder." Presumably after taking Effexor, the same woman glows as she holds her toddler in the air in the ad's feature image. The tagline reads, "I've got my playfulness back."

(Photo credit: Effexor) Published in the American Journal of Psychiatry, 2001

These good mother/bad mother and depressed single lady ads flatten depression, making ordinary life stages such as singledom, motherhood, and menopause seem like conditions that need to be treated. The lack of images depicting people of color and men, who also suffer from depression, is troubling, since depression can be an isolating even when a person is in the target treatment demographic.

Somewhat ironically, the Food and Drug Administration's relaxation of broadcast advertising regulations in 1997 has brought more diversity along with it. Today, television ads include more people of color and men, as well as gender-neutral cartoons, but some of the old stereotypes persist.

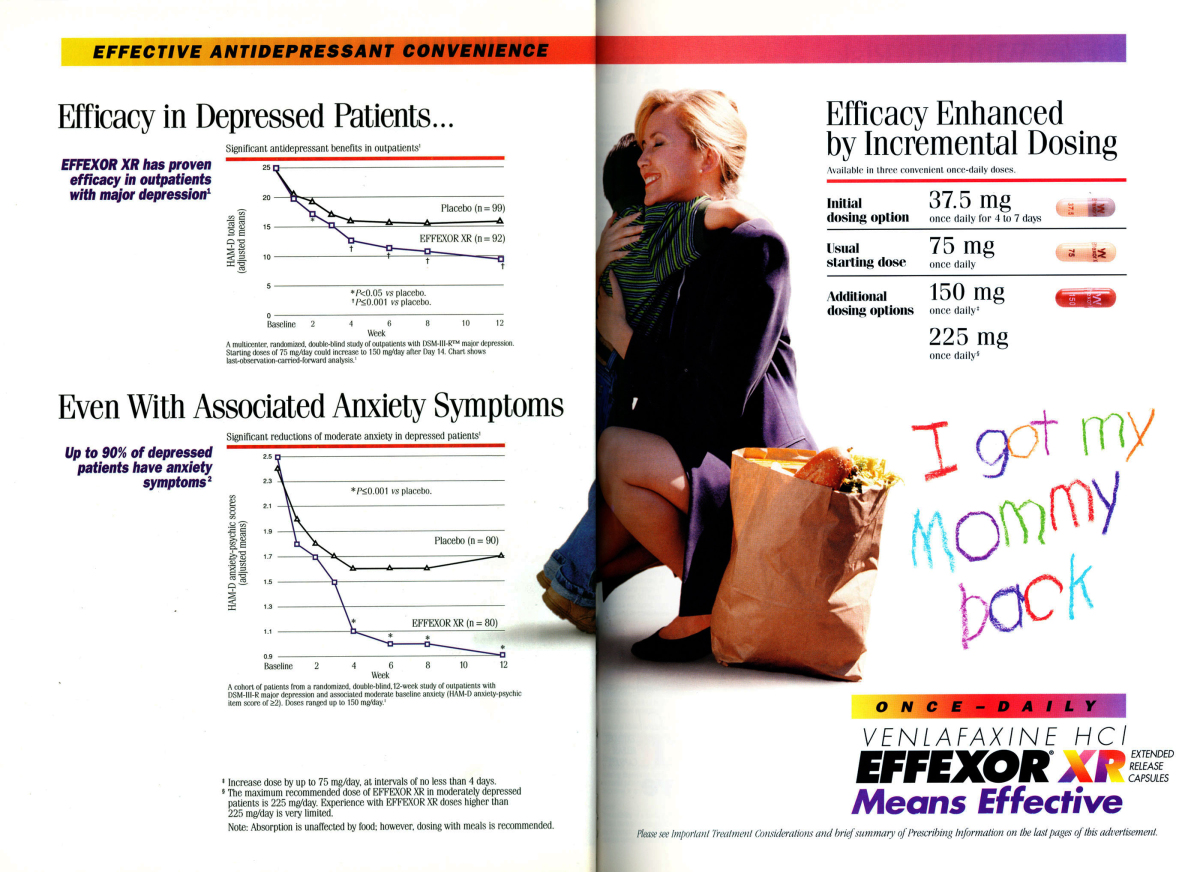

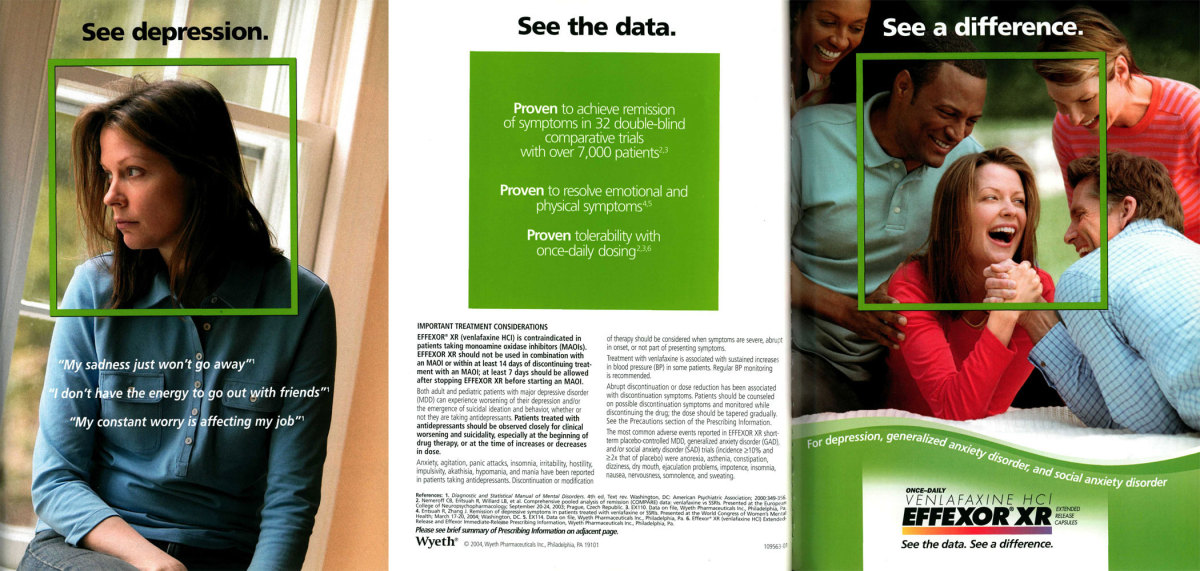

Here are a few more recent ads that span a 6-year period, published in the American Journal of Psychiatry, that demonstrate the clear ways in which pharmaceutical companies got it wrong (and in some cases, they still do). The poor treatment of women in these ads didn't end as women's rights moved into the mainstream. If anything, such advertisements simply shapeshifted, folding anxieties like career achievement and balancing work life and family life into the litany of treatable conditions that affect modern-day women.

Published in 1998:

(Photo credit: Effexor)

Published in 2002:

(Photo credit: Effexor)

Published in 2004:

(Photo credit: Effexor)