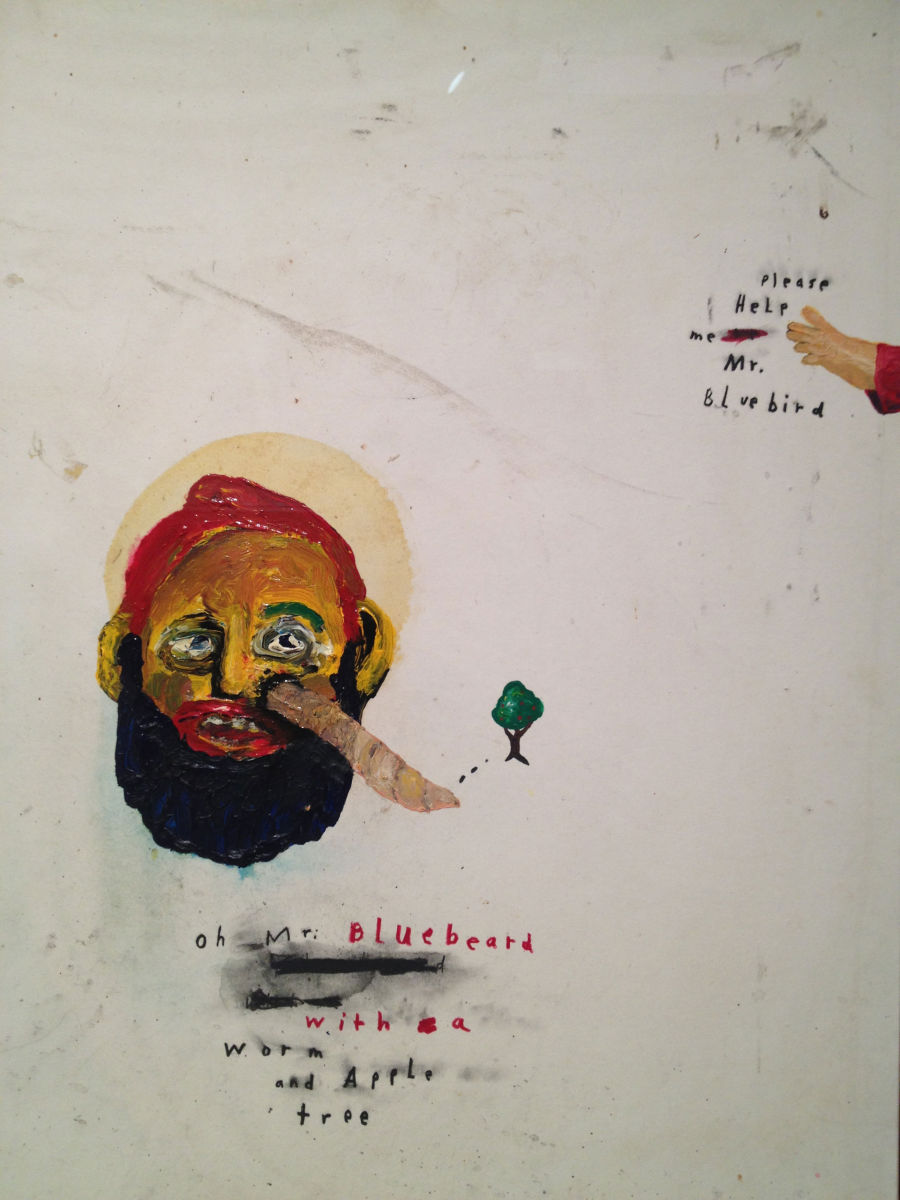

"Oh Mr. Bluebeard with a worm and Apple tree. Please help me Mr. Bluebeard."

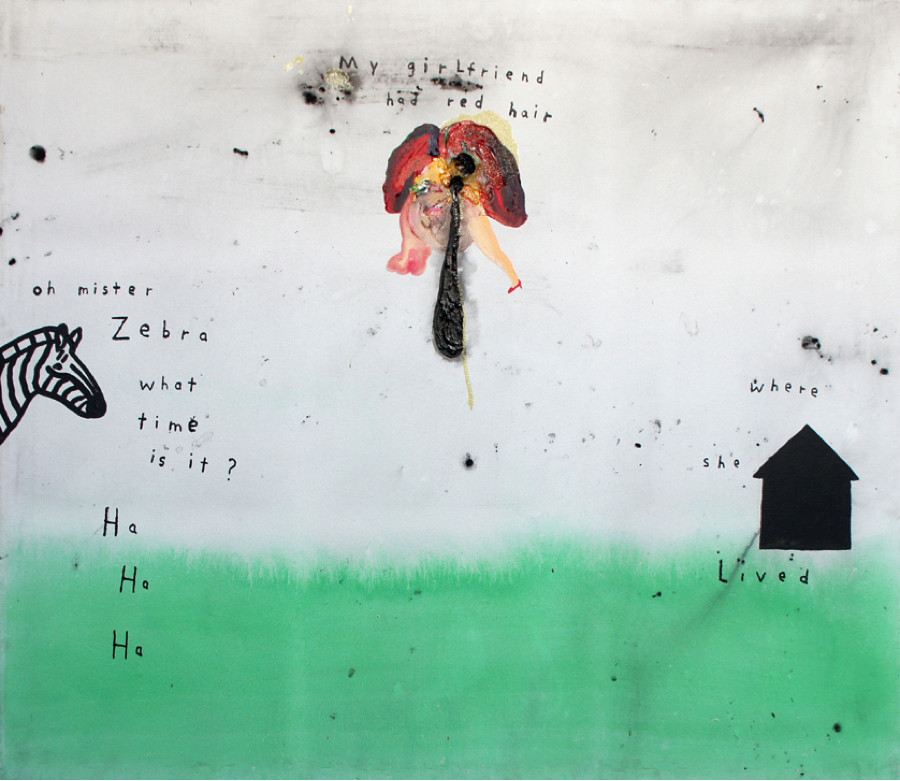

In black and red ink, David Lynch has scrawled this cryptic message onto a canvas, the shaky, scratched-out script looking perhaps like a child's first attempts at handwriting, if not a frantically scribbled final plea for help. In the right hand corner a hand reaches out from nowhere. On the left is a bearded fellow with a giant worm protruding from his cheek.

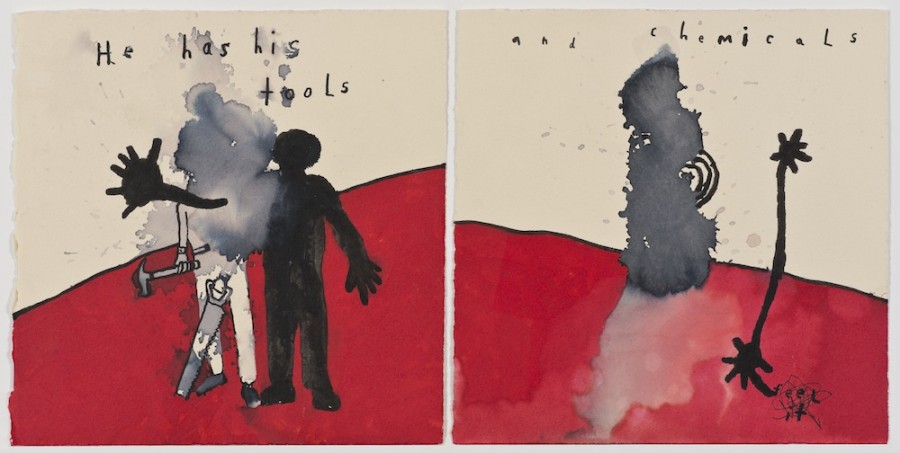

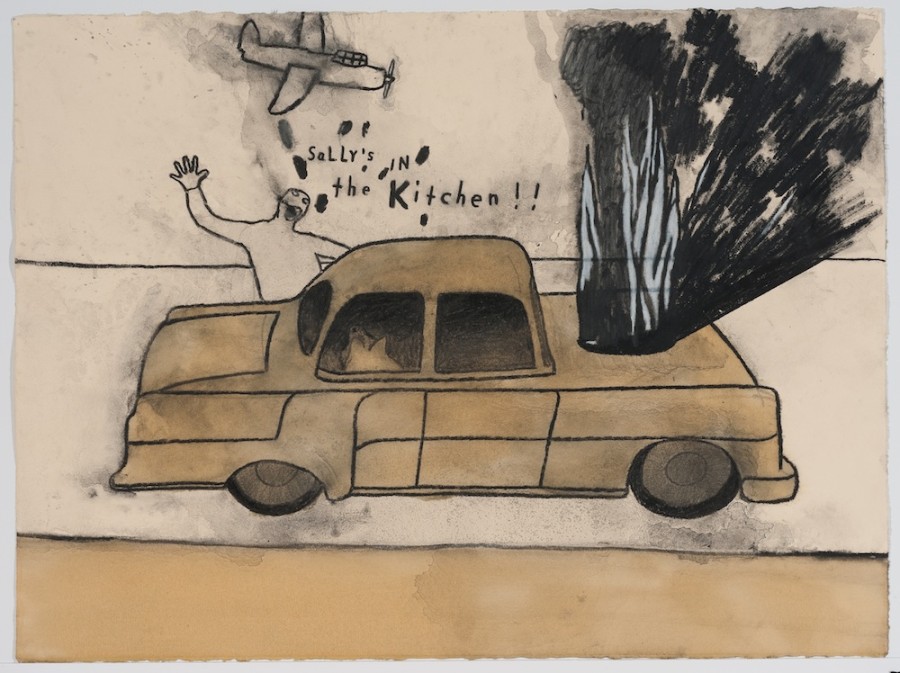

Is this a page ripped from a deranged child's coloring book? A nightmarish hallucination or a sinister poem? The words meander between narrative and nonsense with the same quivering speed that they jump between explaining the image and further muddling it. Even the texture of the words, some of which have been erased or etched away, remains hesitant if not outright mistrustful, an interesting foil to the usual self-assured posture of the image adjacent text on gallery walls.

"Naming," David Lynch's upcoming exhibition at Kayne Griffin Corcoran Gallery in Los Angeles, explores the tenuous relationship between text and image. While we often think of a thing and its name as opposite sides of the same coin, Lynch's work directs us to the instances that reveal a more slippery relation.

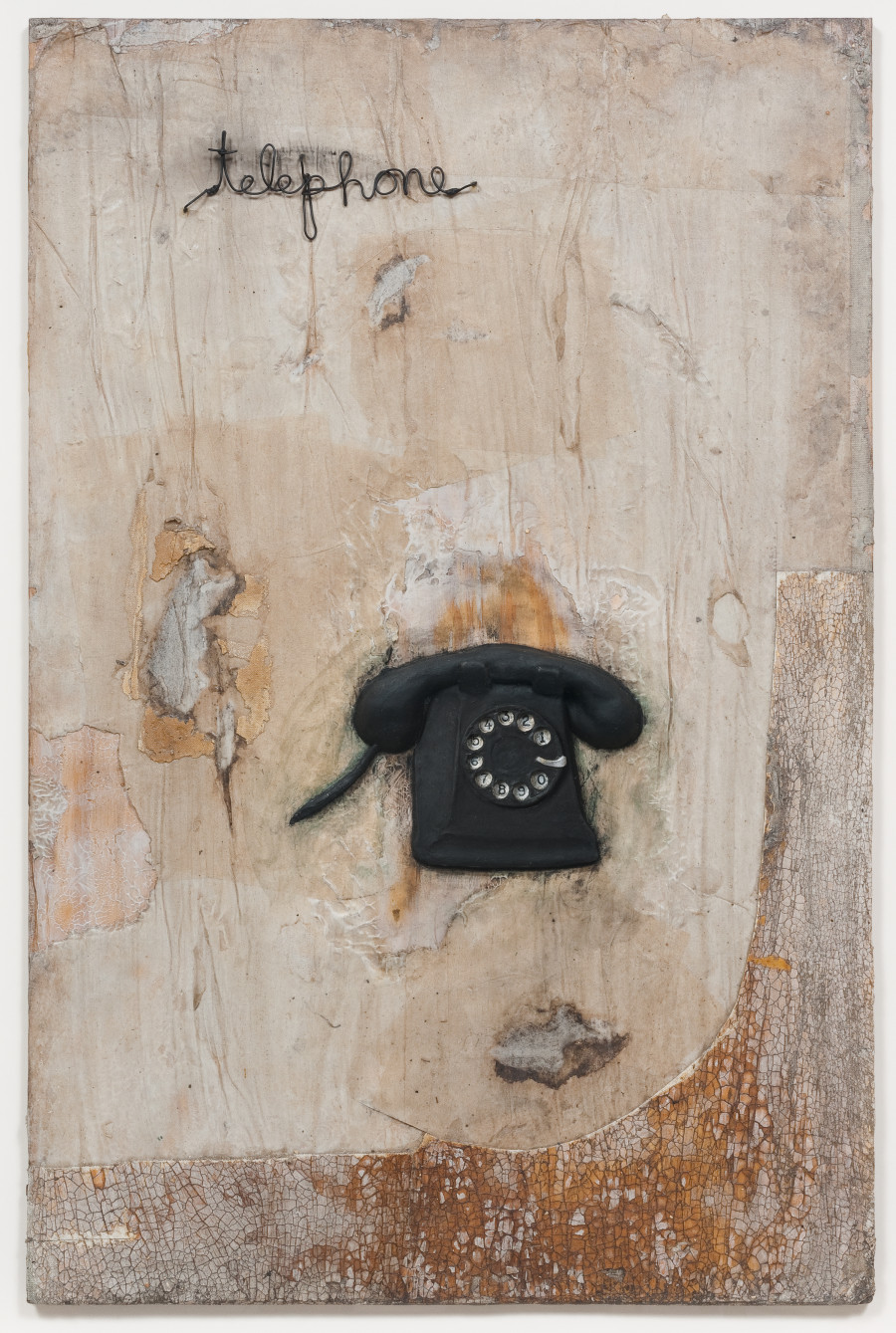

"What's in a name?" curator Brett Littman ponders in an essay for the exhibition, before expanding on the philosophical implications of endowing an image with a correlating word. In Lynch's photographs, letters and words are already embedded in the world, whether hand-written on a poster or mounted on a dilapidated storefront sign. Time has rendered many of the written designations outdated and thus meaningless; they merely wait for their written remains to be updated or replaced.

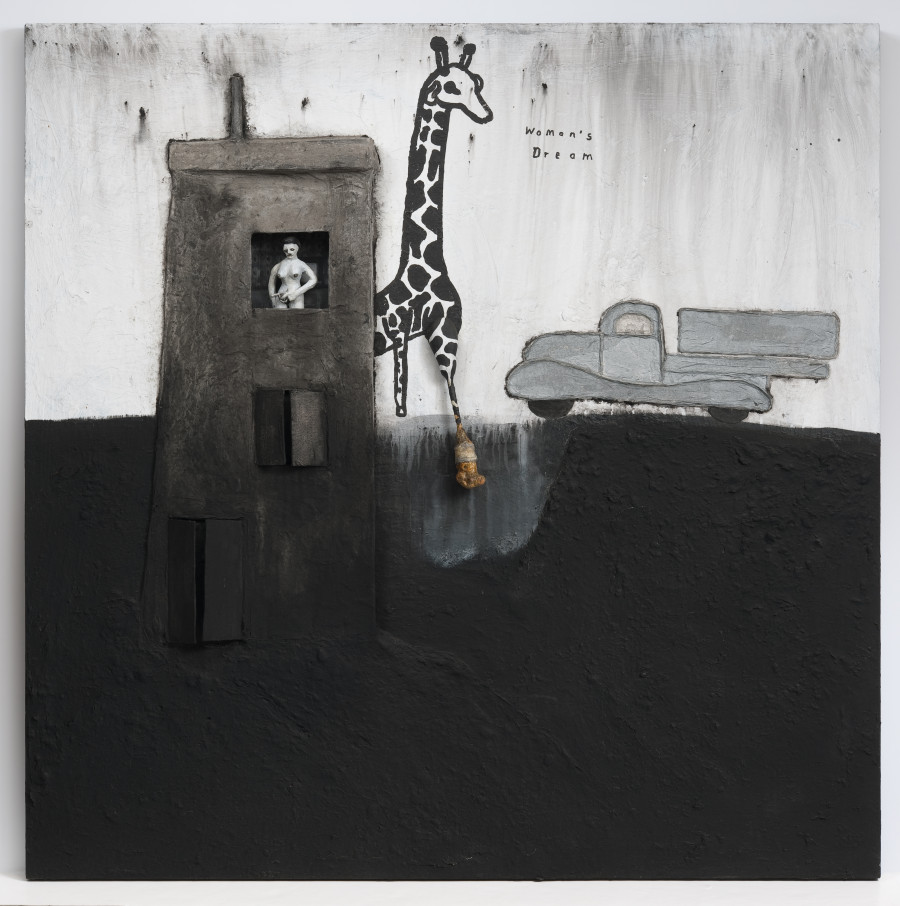

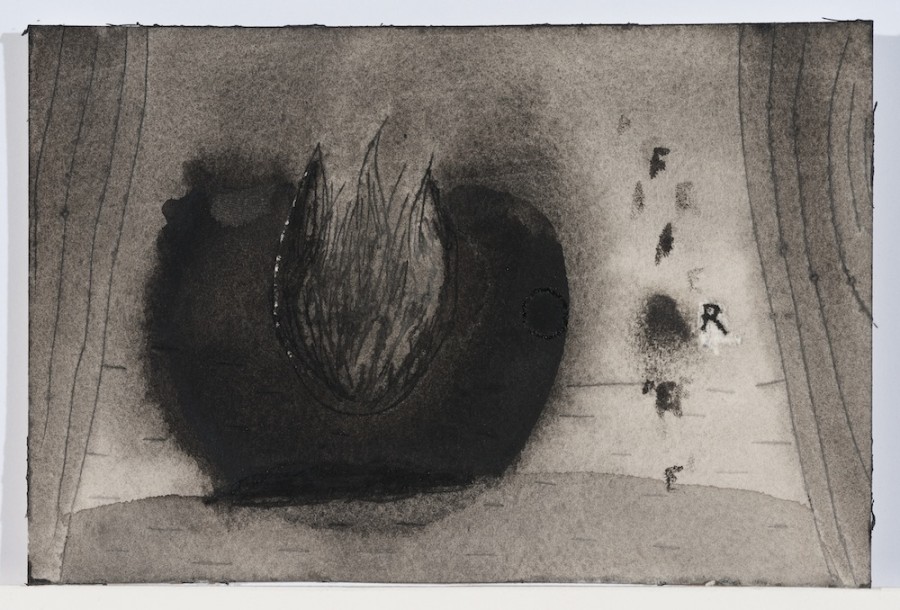

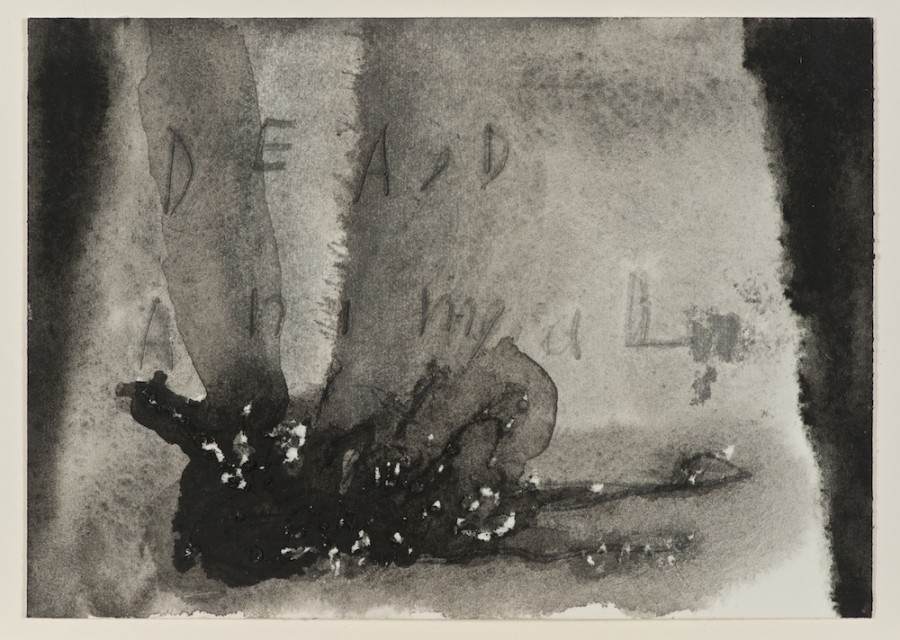

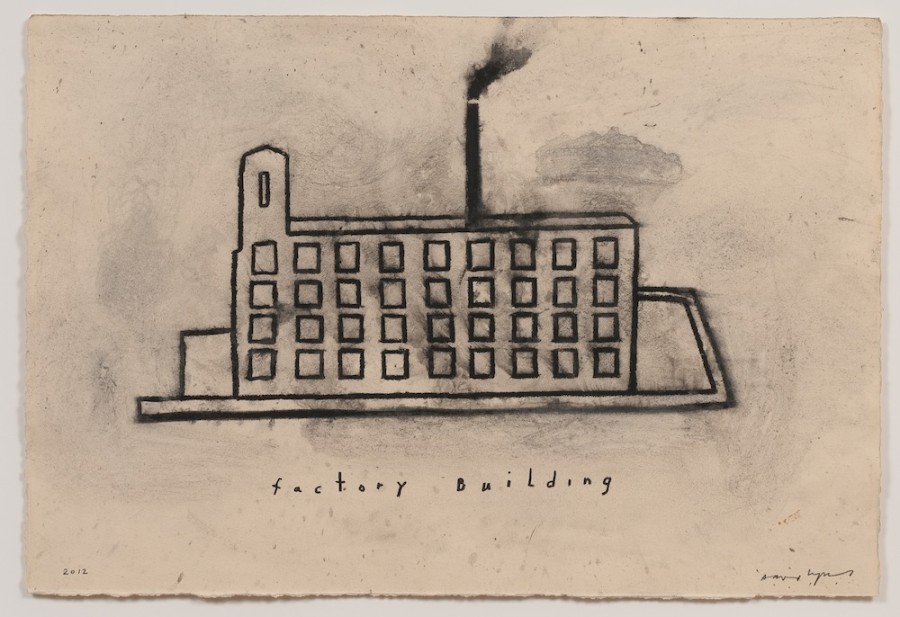

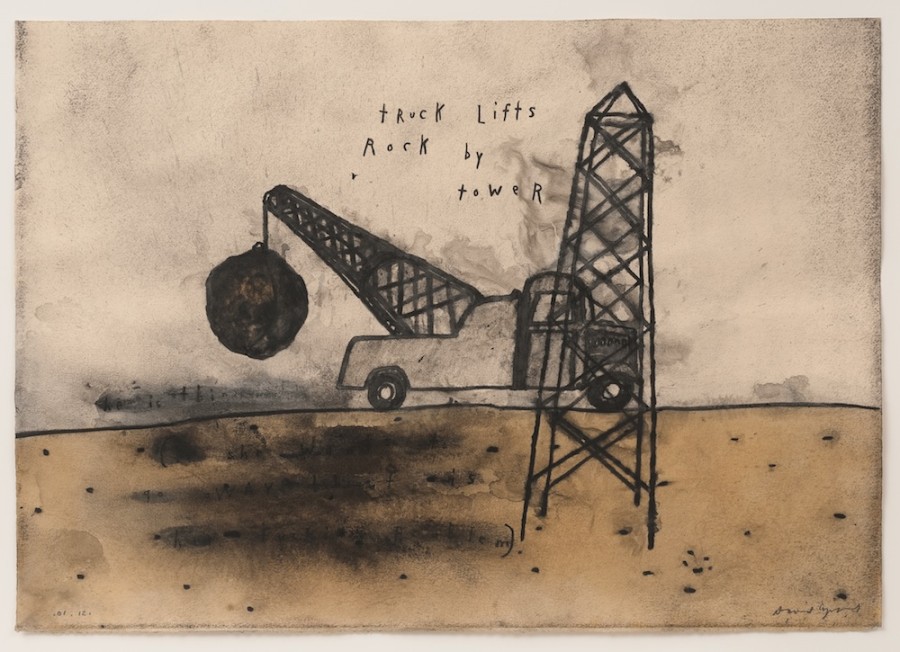

In Lynch's watercolors, language functions altogether differently, with ghostly letters floating around the canvas, so barely legible they function more like additional images than carriers of meaning. In his multimedia canvases, the words Lynch chooses provide clues to understanding the works' dreamlike logic, actualizing the frustration that occurs when language escapes you. Littman combines 61 of Lynch's works, throughout a variety of media and time periods, each employing a slightly different use of language's powers.

If you're a fan of Lynch's films you won't be surprised by his remarkable ability to turn a banal scenario or simple drawing into a warped nightmarish vision. Roaming the exhibition, it's impossible to tell where exactly Lynch's words are coming from and whether they should be trusted. "'David Lynch Naming' highlights how in the Lynchian universe the use of words, sentence fragments, and the act of naming something is never a simple gesture," Littman explains in his essay. "For Lynch, the drawing of an 'ant' and the written word 'ant' are never co-equal or necessarily co-descriptive."

We reached out to Littman to find out more about his unusual curation technique and working with the enigmatic film icon.

What was your relationship to David Lynch's work prior to the show?

David was introduced to me about a year and a half ago by [L.A. gallerist] Bill Griffin. He came and visited me twice at The Drawing Center. I was aware of his artwork dating back to 2006; I was deputy director at MoMA PS1 and we were considering showing his work there. I had some time to familiarize myself with the paintings and drawings he had done at that time. I looked at about 300 or 400 works and one of the things that stood out to me personally was this relationship between text and image.

David has a kind of predilection towards having text and images in every kind of media that he has ever worked in. Be that the photography, the drawings, the watercolors, the prints and also the films. One of the ideas that David and I had was about the concept of naming -- and I mean naming in a spiritual capacity.

How do you mean spiritual?

David is very into transcendental meditation, and there is a spiritual belief that when the gods name things they come into existence. To me, that felt like how David described his own process of naming. He always has to give something a name to make it into some kind of object. For example in one piece, "The Ricky Board," a 1987 drawing, he drew a bunch of rickies, or flies, and gave them proper names like Steve or John or Bucky. He said as he named each of the flies they took on personalities and had a kind of uniqueness to them.

It's a little different from the work that Ed Ruscha and John Baldessari did in L.A. when they were working with text. But then again, it also put David into a context -- maybe standing at a distance from them but it was interesting for to me to juxtapose those things together in my mind.

Many of Lynch's images contain text in them but remain untitled as artworks. How does that factor into his naming practice?

David does not title many of his works but for this show but I think there is always some fragment of text draws him to the work in the first place. To me it's clear that the core of his images is the text itself, that's what drew his eye. The photography for me was the real revelation. These are very much like Robert Adams' 1970s photos, these almost banal, abandoned buildings in the landscape.

How is the exhibition organized?

I made a list of words featured inside the artwork and the whole show could be read almost as a concrete poem by stringing together these words. The exhibition is not chronological, it's not by media. I wanted it to be a little bit filmic.

Was this something you and Lynch came up with together?

I brought the idea to the table. David has a healthy skepticism of the word curation, I think. Over the course of these few days we had a bunch of conversations and I had time to convince him. He was very enthusiastic and excited that I found something that interested me, but I would not say most of his work is about that particular issue. He's not really nostalgic, he's not looking to the past. The work that he's made, he's made it, he exists. I think a lot of David's shows have tended to be somewhat uncurated and so I'm giving a framework, though it's certainly not the only interpretation of David's work.

Your exhibition essay touches on what it means to name an object according to theorists including Plato, John Locke and Ludwig Wittgenstein. How would you describe Lynch's approach?

I think that, for me, the earlier drawings in the 2000s, the very muddy, almost unreadable scratch text drawings display a real distrust of language as a universal tool of communication. There is a view that the inherited language that we've learned has to be unlearned. Since that time I believe that there is a little bit more clarity. The images that he's made are much less dark, less muddy.

Does this perspective of language translate into his films as well?

It definitely is consistent with "Alphabet," an early film which is also on display in the exhibition. And even in Twin Peaks, with the midget speaking backwards, you can see how words mean one thing but can also mean something else. Yet today I think David is communicating something slightly different, maybe as a result of his meditation. Some of the works are quite dark, but there are some new drawings that I've published in my catalogue that have that kind of clarity to them. I think it's interesting to see that kind of shift. I think it's interesting to look at a person's work and see the progressions and the changes.

Do you think it's fair to say that instead of the words serving as captions for the images it's become the opposite? That the images are captions for the words?

I think it's a little more complicated than that. David and I talked about the way children point at things. The first acquisition of language by children, where everything is wonder. I kind of describe it as vibration. Sometimes the image comes first and a word is applied after. The name gives them a fission and a sense of meaning.

Then there's that kind of slippage from knowing what's real and what's not. When things are a little bit hard to comprehend -- that's when the world gets interesting, when things start to break down. It happens to people with old age and Alzheimer's. Sometimes we look at something and lose the word for it; you have to re-find it and redefine it.

After working so closely with Lynch, how intentional do you think his work is?

I think his filmmaking and artmaking are two very different things. The filmmaking requires groups of people, full teams, and years of work. The artwork is a kind of respite from that; he was trained as an artist first, he studied painting. His first two student films, "Alphabet" and "Six Guys Projecting" were made to kind of animate the paintings. Whether or not his work is intentional -- I think ideas come through meditation, they come through deep reflective thinking and then something kind of snaps together and then he moves on to the next instant. It's a reflection of something immediate. It may or may not have deeper meaning.

"David Lynch Naming" runs from November 23 until January 4 at Kayne Griffin Corcoran Gallery in Los Angeles.