Warning: This article contains graphic and violent imagery.

Many of us digest incidents of violence on a daily basis, via our local newspaper or digital media of choice. But how have these images of crime and its gruesome aftermath transformed over the course of the last century? An exhibition entitled "Crime Then and Now: Through the Lens of the Chicago Tribune" spans the history of crime photography through a particular publication, revealing the ever shifting ways we view violence in the world around us.

Back in the 1920s, '30s and '40s, crime photography was a whole different breed than it is today. For starters, there were big name photographers like Arthur Fellig, also known as Weegee, who roamed the night-cloaked streets with almost supernatural intuition, capturing dizzying, behind-the-scenes shots of sensational gore. With his handy Speed Graphic camera, Weegee turned murder and crime into a spectator sport, snapping intimate shots that did away with any figurative caution tape between the viewer and the scene of the crime.

Joseph Schuster, center, was identified by robbery victims as the killer of policeman Arthur Sullivan. Policeman Arthur Sullivan, 38, of the Marquette station, was shot and killed at the Kedzie Ave. station of the Douglas Park "L" branch near 20th Street on Jan. 14,1937. Sullivan, off duty, was on his way home when he was stopped by a clerk from a nearby pharmacy who pointed out a man who had robbed the pharmacy the day before. Policeman Sullivan trailed the man to the "L" station when he confronted him. According to the Chicago Daily Tribune, the suspect said "Officer, I'm a law abiding citizen." As Sullivan marched the man down the stairs to the middle platform, the suspect grabbed a gun from a hidden left shoulder holster and shot Sullivan in the head. Sullivan left a widow and four children, the youngest was two and the eldest was 15 years old. Paroled convict Joseph Schuster, 30, was later convicted of killing Sullivan and sentenced to die by the electric chair. Chicago Herald & Examiner photo. (glass negative)

In major cities across the country, crime photographers followed Weegee's lead, getting up close and personal with the most illustrious murderers, robbers and bandits of the day. At the time, law enforcement officials allowed, and even encouraged, photographers to immortalize the grisly aftermath of lawful misconduct. Even the criminals themselves weren't opposed to posing for the camera, with kingpins like Al Capone and John Dillinger hungry for press.

"In the old days, photographers were very much working with the police," Tribune photo editor Michael Zajakowski explained to Slate. "They were stationed at police precincts, and they’d be sitting next to the sergeants when calls came in -- they’d be able to run out to a scene and get there sometimes even before the police." Zajakowski co-curated the exhibition, along with Gage Gallery’s Tyra Robertson.

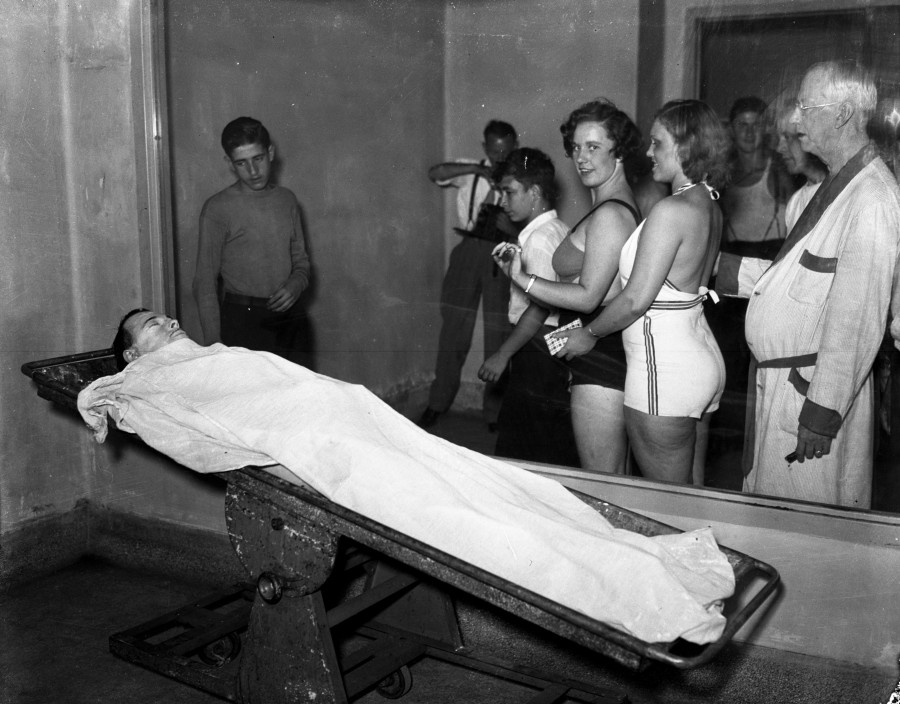

Betty Nelson and Rosella Nelson view the body of John Dillinger while in bathing suits at the Cook County Morgue, located at Polk and Wood Streets, in Chicago. In the days after Dillinger was killed on July 22, 1934, massive crowds lined up outside the morgue to get a glimpse of the notorious public enemy.

The resulting images from this early photo era were deliberate and intimate, planned with permission and unafraid to revel in all the dirty details. Many of such chilling and iconic images appeared in the Chicago Tribune. In one photo, two ladies clad in bathing suits push to the front of the crowd to catch a glimpse of Dillinger's corpse at the Cook County Morgue. In another, 16-year-old Donald Jay Cook reads a book in Cook County jail during his sentence for killing a fellow 16-year-old and stuffing him in a closet.

If you've looked at a newspaper in the past few years, we don't need to tell you things have changed quite a bit. For one, photojournalists and police forces aren't quite so cozy, and thus that vintage class of insider images is no longer in reach. Furthermore, the public's collective thirst for the bloody details is no longer en vogue, and explicit images are often deemed insensitive and cruel in the face of human suffering.

Contemporary crime photojournalists, then, have veered toward more emotion-driven narratives, capturing the victims and their loved ones instead of the moments directly following the event itself. "We’re not just going to a crime scene, photographing what’s there and walking away," said Zajakowski.

Judy Young, center, whose six-month-old daughter Jonylah Watkins was killed at 65th and Maryland Ave. in Chicago on March 11, 2013 has her photo taken at the scene of the shooting the day after it occurred, surrounded by family and friends. Jonathan Watkins, Jonylah’s father, was changing his infant daughter's diaper in a parked minivan when a gunman walked up and shot both Monday afternoon in the South Side's Woodlawn neighborhood. Jonylah was killed by a bullet meant for her father. Police say Willis believed Jonathan Watkins had stolen the Sony PlayStation of the gunman. Nancy Stone photo.

In early 2013, the Tribune tweaked its photography methodology once again, creating an an overnight crime beat with reporters on call from 9 p.m. to 9 a.m. The new nocturnal shift produced a contemporary body of work that captured the reality of serious crime in one of the most violent cities today. The images focus on human expressions of pain and anguish, as well as the physical imprints of violence on the flesh. Not to mention, the black-and-white images of yore have been replaced with saturated prints charged with color and detail.

How has the strange beast that is crime photography changed over the past century? Everything from its perspective to its palette have been revamped according to the norms of the time, though some aspects remain untouched. Whether in 1920 or 2015, crime photographs still have that magical ability to attract and repulse, to reveal at once too much and too little, to tell stories we wish did not exist but still love to divulge.

"Crime Then and Now: Through the Lens of the Chicago Tribune" runs through April 11, 2015 at Gage Gallery at Roosevelt University in Chicago. See a preview below.

Related

Before You Go