Today many, if not most, artist-photographers incorporate issues of theater, sexuality and the constructed self into their work. From Cindy Sherman's multiple personalities to Robert Mapplethorpe's homoerotic bodies, photographs no longer present their subject, they create their subject. Yet few were experimenting with the relationship between art and the self in the late 19th century. F.Holland Day was. We can see the results in a new book by Yale University Press, as well as a new exhibition at the Addison Gallery of American Art.

Day was born in 1864 to a wealthy family outside Boston, and grew up immersed in literary culture, mainly the work of John Keats. As much as he liked being a bibliophile, he also enjoyed looking like one, dressing up like an eccentric bookworm with glasses, cane and top hat. The thespian in Day was present from an early age, and when he started experimenting with photography in 1880 the camera became a stage par excellence.

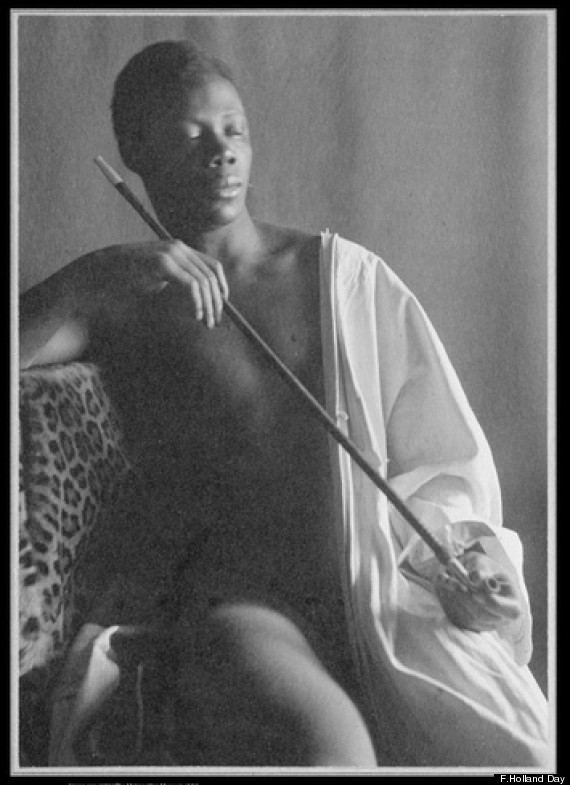

A peer of Alfred Stieglitz, Day became involved with Symbolist and Decadent movements, transforming religious and historical iconography into mythical, surreal imagery. Throughout his life Day faded into oblivion for reasons both aesthetic and personal: many interpreted his ahead-of-his-time performance photographs as perverse. Some featured scantily clad young boys in Grecian robes. Another featured a black man dressed as a cosmopolitan dandy. Aesthetics ruled over the politics of the time, charged imagery was just more imagery for Day. Others took issue with his close relationships with men. For most of his life Day kept his sexuality hidden in accordance with the standards of his era, telling his friends he was "married to his camera." Yet Day moved in with a man (platonically) later in his life and published a poetry on the history of male-male friendship from pagan to modern times.

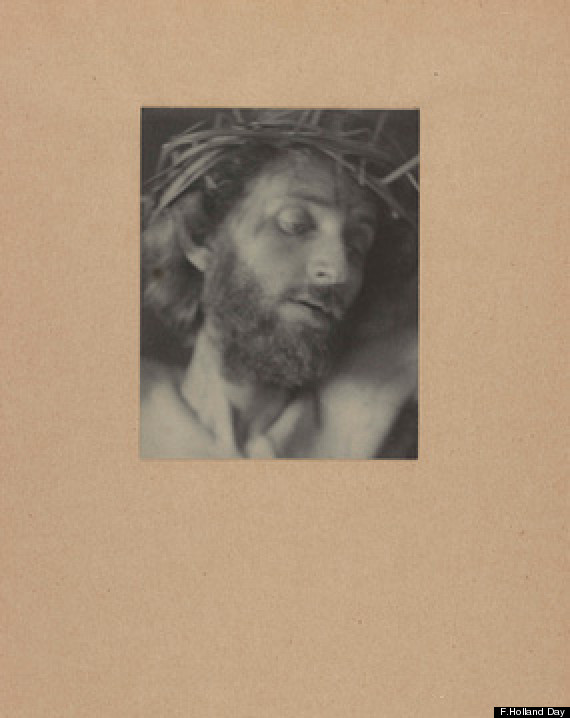

In his most famous (and criticized) series, Day portrayed himself as Jesus in a variety of poses. He lost weight for the role and gives a surprisingly heart-wrenching performance whether on the cross or gazing into the camera. Far before Andres Serrano pushed the Jesus envelope with "Piss Christ," Day's provocative costume invited accusations of immorality.

Day's photographs, playing with identity, race and gender as if they were all different costumes to be tried on, were over a century ahead of their time. Some subjects look like flower children in a 1960's cult while others look like royalty in an Ancient Arabian myth. He possessed a radical ability to see beyond categorization, but also a radical ability to see beauty. His works are timeless, combining a Pre-Raphaelite ethereal beauty and a post-modern proliferation of self.

"Making a Presence: F. Holland Day in Artistic Photography" is on view until July 31, 2012 at Addison Gallery of American Art in Andover, MA, and is curated by Trevor Fairbrother.