This week offered a status update on Facebook's efforts to get people to embrace its phone: Its much-hyped Home software, engineered to put Facebook front and center on smartphones in every way possible, has so far been a bust.

Home has been downloaded fewer than one million times -- small change for a company with more than one billion users -- and the first smartphone to come pre-loaded with Home has had its price slashed from $99 to 99 cents. On top of that, more than 15,000 reviewers on Google Play, Google's app marketplace, have decided that Home merits no more than two stars.

But in taking stock of Home's flop, most have ignored the fact that we already have Facebook phones: They're our iPhones. (Or really any other smartphone with a Facebook app)

Facebook has become so pushy about its on-the-go alerts that the primary screen of my phone has already been taken over by Facebook notifications -- less visually appealing than Home's news feed, but just as brash. My Apple smartphone more and more feels like a Facebook smartphone: the social network is aggressively using our conversations with friends as an entrée into starting a conversation with us. And in so doing, it risks alienating the very people it needs to keep hooked through the very medium it most needs to master.

In its urgent bid to show its network is gaining mobile users more quickly than it's losing desktop ones, Facebook has become the annoying, tone-deaf relative who calls daily to ask why you haven't responded to his email, interrupts with unfunny jokes and forwards every spammy chain letter, no matter how often you ignore him. Like your irritating but occasionally endearing second cousin, Facebook is tolerable in small doses and is connected to too many people you care about to be excised completely.

Facebook, invited onto our phones, has taken advantage of having access to us at anytime. Home's lackluster success may stem from our unpleasant interactions with Facebook on our other phones: We can't trust Facebook to know how to behave. It's a social network with no social skills. And it seems we don't need a Home-powered phone because whatever smartphone we're carrying is already dominated by Facebook.

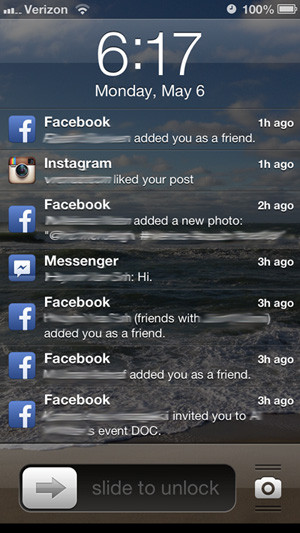

Facebook took over my iPhone's screen on a recent Monday.

Facebook took over my iPhone's screen on a recent Monday.

For several years now, I've toted Facebook's app around with me on my iPhone, where it's offered a convenient portal into my online social life and occasional updates that pushed to the front of my screen. But over the past few months, Facebook has morphed from a source of once-in-awhile reminders to a chatty, jabbering nuisance that seems dead-set on carrying on a constant conversation with me throughout the day.

I'm not alone, according to Chris Silva, an analyst with the research firm Altimeter Group. As the frequency with which people check Facebook on their computers has dropped, the social network, eager to offset the decline with a bump on mobile use, has been making a non-stop pitch to get people hooked on Facebooking with their phones. Facebook hopes to show advertisers that their dollars will be well spent on mobile devices, even if their ads are smaller, Silva notes.

"There's absolutely been an increase in frequency and perhaps even the number and type of notifications users are getting," Silva said. "They're trying to use these things as the Trojan Horse ... to bring me into the app more frequently and for longer periods of time, which then sets the stage for having higher engagement numbers when advertisers are pushed more heavily toward mobile."

"It's very clear that in the last couple of months, Facebook has ratcheted up their engagement game," Silva added.

Facebook has turned my phone's screen into a real-time stream of updates from people I don't much care about doing things I'm not too interested in. On Monday alone, Facebook sent me about a dozen push notifications -- those eye-catching alerts that pop up on the phone's front screen, make it vibrate and send its speakers dinging. It's the same mechanism local governments use to send emergency alerts, and the same format Apple uses to alert you to text messages.

Here are just a few of the crucial updates Facebook deemed important enough to push to my iPhone's screen: an invitation to an event still weeks away; an invitation from someone I barely know to play an online game; four friend requests from people with whom I have zero friends in common; a photo shared by a person I knew in elementary school; and a comment left by someone I don't know on a Facebook post I don't remember making.

Of course some of these notifications are unique to me -- I'd guess I receive a higher-than-average number of friend requests by virtue of my job -- and they can all be silenced or tweaked in Facebook's privacy settings.

Yet the social network, left to its own devices, has still taken the liberty of using our phones as its broadcast channel.

Most intrusive of all have been the alerts, received by myself and others, suggesting we chat with someone who's just logged onto the social network, post a status update, or buy a friend a birthday gift using Facebook's gift-giving service.

In these cases, it feels like Facebook has committed the ultimate sin of assuming people want to hear from it, whereas the whole point of signing up for the social network was to hear from friends. When Facebook pushes people to fork over their credit card numbers to buy something through its service, it underscores that it has also decided it's entitled to bug us with what it wants to tell us -- and do so in the most in-your-face way possible.

"Because mobile devices are our most personal screen, consumers have a far lower tolerance for interruptive, brand-centric communications," Corey Gault, director of communications at the mobile marketing firm Urban Airship, said in an email.

Gault said he had received the impression that Facebook was seeking to better monitor users' reaction to its alerts -- that they would stop sending push messages to people who'd been inactive for more than 28 days and only continue messaging people who clicked on a certain number of notifications. But that hasn't happened, he argues.

"Facebook is not really practicing Good Push itself, sending many messages that serve its own interests, not its users," Gault noted.

Twitter is littered with complaints from other users who've felt needlessly interrupted by Facebook push notifications urging them to ask a question, update their status or chat with a friend who's just come online.

"Jesus christ Facebook just sent a push notification to say an old flame is online, and that I should chat her," tweeted Derek Mead, managing editor of VICE's Motherboard, in February. "Horrifying. Is this new?"

Another user, @SetsuPorcelain, tweeted earlier this week, "Facebook, what u doin'? I asked NO PUSH NOTIFICATION STOP ruining everything."

A website and app designer, @juice49, got especially angry, tweeting this week, "Facebook, this should not be a notification. Don't push this sh*t to me."

Facebook, a glutton for data, is presumably closely monitoring our interactions with its notifications for signs that we're either irritated or intrigued.

But bear in mind that Facebook has never been dissuaded from a course of action simply because it's proved annoying to its users. And unlike an irritating relative, Facebook doesn't just seek to control its own behavior, but to mold yours.