So, like every other one of the world's 1.28 billion monthly active Facebook users, you blindly agreed to Facebook's Terms and Conditions without reading the fine print.

You entrusted your photo albums, private messages and relationships to a website without reading its policies. And you do the same with every other site ... sound about right?

In your defense, Carnegie Mellon researchers determined that it would take the average American 76 work days to read all the privacy policies they agreed to each year. So you're not avoiding the reading out of laziness; it's literally an act of job preservation.

So here are the Cliffs Notes of what you agreed to when you and Facebook entered into this contract. Which, by the way, began as soon as you signed up:

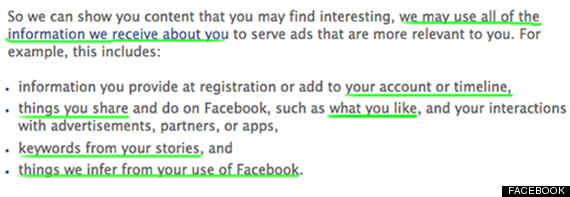

Nothing you do on Facebook is private. Repeat: Nothing you do on Facebook is private.

Note the rather vague use of the word "infer," which Oxford Dictionary defines as "Deduce or conclude (information) from evidence and reasoning rather than from explicit statements."

That includes some things you haven't even done yet.

Facebook has even begun studying messages that you type but end up deciding not to post. A recent study by a Facebook data analyst looked at habits of 3.9 million English-speaking Facebook users to analyze how different users "self-censor" on Facebook. They measured the frequency of "aborted" messages or status posts, i.e., posts that were deleted before they ever were published. They studied this because "[Facebook] loses value from the lack of content generation," and they hoped to determine how to limit this kind of self-censorship in the future. While a Facebook spokesman told Slate that the network is not monitoring the actual substance of these messages, Facebook was able to determine when characters were typed, and whether they were posted within ten minutes of being typed.

Even if you leave the network, not all your information does.

Your Facebook footprint doesn't necessarily disappear if you deactivate your account. According to the site's Statement of Rights and Responsibilities, if your videos or photos have been shared by other users, they will remain visible on the site after you deactivate your account, and are subject to that user's privacy settings.

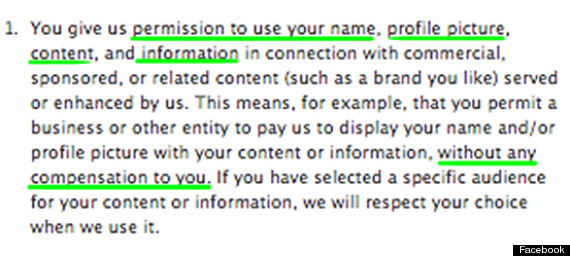

Your information lets Facebook sell the power of your profile to brands and companies.

This means that Facebook is being paid for supplying your endorsement (which you indicate by liking a page) to brands or companies. You can even find out how much your data is worth to Facebook by using the FBME application from Disconnect, Inc. And a report from The Center For Digital Democracy shows marketing companies are taking note, creating algorithms for determining key social media "influencers." The report found that many marketers have identified multicultural youth users as key influencers, and have targeted those demographics with heavier social media marketing.

You're also giving Facebook the ability to track your web surfing anytime you're logged into the site.

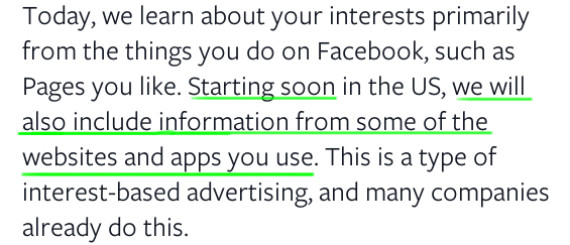

This announcement came in a recent post from Facebook.

Facebook notes that other websites do the same thing. But that accounts for an insane amount of potential data, especially given the growth of Facebook mobile use. On average, Facebook mobile users check the site 14 times a day on their devices.

Facebook also uses strategic partnerships to track your purchases in real life.

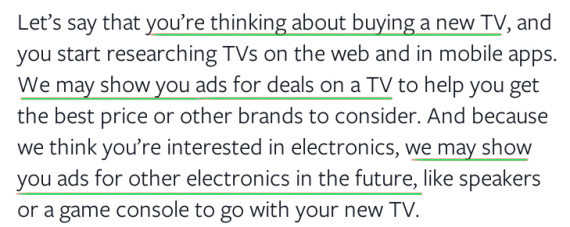

Last year, Facebook started partnering with data broker firms. Data brokers earn their money by selling the power of your consumer habits and monitoring your online and offline spending. Facebook's partnership allows them to measure the correlation between the ads you see on Facebook and the purchases you make in-store -- and determine whether you're actually buying in real life the things you're seeing digitally while using Facebook. Two of Facebook's partners, Datalogix and Acxiom -- one of the oldest data brokers and a partner of Huffington Post's parent company AOL, Inc., -- were among the nine data brokers the Federal Trade Commission analyzed in a recent in-depth study. The study found that data brokers "collect consumer data from numerous sources, largely without consumers' knowledge" and "store billions of data elements." Acxiom has a database of about 3,000 data segments for nearly every U.S. consumer.

Brokers share this information among "multiple layers of data brokers providing data to each other," and then analyze the date to make "potentially sensitive inferences" about the consumer. These sensitive data points could range from health specifics, like high cholesterol, to broader demographic categories -- like the so-called "Urban Scramble," which includes a "high concentration of Latinos and African Americans with low incomes" or the so-called "Rural Everlasting," which includes single men and women over the age of 66 with “low educational attainment and low net worths."

Some other examples of data points the FTC noted:

- Presence of Elderly Parent

- Presence of Children in Household

- Birth Dates of Each Child in House

- Single Parent with Children

- Ethnic and Religious Affiliations

- Home Size

- Market Value

- Date of Move

- Gambling - State Lotteries

- Affluent Baby Boomer

- Type of Credit Cards

- Date of Last Travel Purchase

- Buying Activity

- Working-Class Mom

- Buying Channel Preference (e.g., Internet, Mail, Phone)

- Average Days Between Orders

- Last Online Order Date

- Last Offline Order Date

- Smoker in Household

- Allergy Sufferer

- Weight Loss & Supplements

- Expectant Parent

The data collection is difficult to skirt. One Time Magazine reporter went to great lengths to hide her pregnancy from big data; she said her husband ended up looking like a criminal when he went to a drugstore and tried to purchase enough Amazon gift cards to buy a stroller on the website. This kind of ultra-specific marketing also can become eerie. Take the case of Mike Seay, who the LA Times reported received an OfficeMax marketing letter addressed to "Mike Seay, Daughter Killed in Car Crash." OfficeMax said that the information came from a third-party broker, but did not specify which one.

Facebook uses all this outside information to target ads to you.

This past June, Facebook announced that it would start using data from users' web browsing history to serve targeted advertisements as such:

Of course, targeting ads is hardly a new phenomenon; Nielsen started gathering information about radio audiences back in the '30s. But because Facebook has so much information on every user, the kinds of demographics they make available to advertisers are more comprehensive.

For example, a company could specify its audience, said Facebook, "to target people who recently moved and are engaged or in a relationship and in the industries of Accounting and Finance."

When Facebook introduced its ad targeting, it said, "When we ask people about our ads, one of the top things they tell us is that they want to see ads that are more relevant to their interests."

But that explanation doesn't really tell the whole story. While some users may not mind being shown targeted ads to help them pick out a new TV, this example brushes over the full scope of items being marketed to you based on your data. For instance, according to a report from the Center for Digital Democracy, financial service companies have taken to Facebook for "data mining, targeting, and influencing consumers and their networks of friends," and some companies are developing "new leads for their loan and refinance offers" based on users' Facebook behavior.

And the finance world is not a small amount of Facebook's advertising platform: According to a Business Insider investigation, Visa, American Express, Capitol One and CitiBank are among the top 35 biggest advertisers on Facebook. When Facebook describes its newly implemented changes, it doesn't seem as eager to discuss the financial plans it might be helping the companies sell you.

So who really benefits from these highly targeted ads? For one, Facebook itself. Facebook's ad revenue grew 82 percent from 2013 to the first quarter of 2014, totaling $2.27 billion. Joseph Turow, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Annenberg School for Communication, told the New York Times that this new user tracking is making Facebook one of the fastest-growing advertising companies on the Internet. "It's more likely to help Facebook than you," he said.

If you're not very keen on helping Facebook generate more profitable ads at the price of your privacy, Facebook suggests you choose the "x" out option on individual ads. This won't change the data being gathered about your interests, but it should help prevent an influx of credit card ads from popping up on your Facebook.

If you want your targeted ads to stop completely, Facebook recommends you use the industry-standard opt-out program from Digital Advertising Alliance.

However, those two recommendations have been dismissed by privacy advocates like Jeff Chester, executive director of the Center for Digital Democracy, who called them "a political smokescreen to enable Facebook to engage in more data gathering." FTC chairwoman Edith Ramirez has also urged the wider digital advertising community to create a "more persistent method" of opting out that would give consumers more control.

According to a Consumer Reports poll, 85 percent of online consumers oppose Internet ad tracking.

Facebook has been rolling out location services that effectively turn mobile phones into location tracking devices.

![]()

What's next when it come to information gathering by Facebook? TechCrunch spotlighted Facebook's new tracking feature, "Nearby Friends," which is being pitched as an opt-in way to find out which of your friends is located within a mile of you. While you don't receive the exact location of your friends, Facebook receives your exact location. The feature uses "Location Tracking" to create your "Location History." While you can clear your history and turn off the app at will, Facebook noted that it "may still receive your most recent precise location so that you can, for example, post content that's tagged with your location or find nearby places." So some amount of tracking is happening, no matter what.

And it plans to use this location data to sell you things.

Back when Facebook unveiled "Nearby Friends" in April, a company spokesman conceded to TechCrunch that "at this time [Nearby Friends] is not being used for advertising or marketing, but in the future it will be."

It wouldn't be surprising if Facebook did, indeed, begin selling location-based data to marketers. After all, studies confirm that this advertising is very successful at convincing you to buy things. A recent U.K. study conducted by media strategy company Vizeum and direct marketing agency iProspect found that location-based advertising created an "11 percent increase in store visits among more than 172,000 people that were served adverts." This technology is only going to become more sophisticated with the rise of more location-tracking apps that can follow your movements in-store.

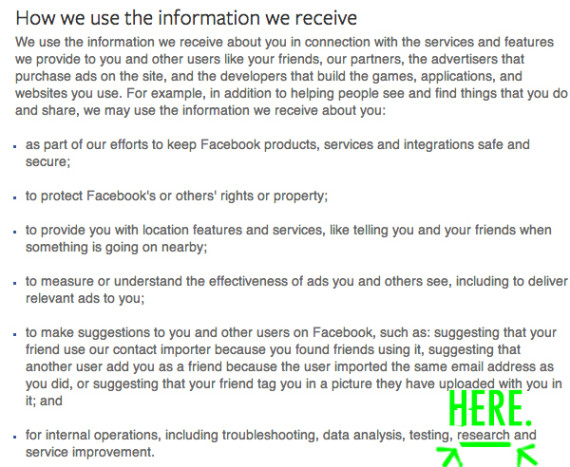

And, yes, Facebook can use you and your data for research.

They say so right...

Yeah... right there.

Despite that "research clause," you may have been surprised to learn that Facebook experimented on nearly 700,000 Facebook users for one week in the summer of 2012. The site manipulated their News Feeds to prioritize positive or negative content, attempting to determine if emotions spread contagiously through social networks. There was no age restriction on the data, meaning it may have involved users under 18. Cornell researchers then analyzed Facebook's data. The resulting study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, found that emotional states can be transferred via social networks. Company executive Sheryl Sandberg has since apologized for the study, calling it "poorly communicated."

Andrew Ledvina, a former data scientist at Facebook from early 2012 to the summer of 2013, told the Wall Street Journal that Facebook did not have an internal review board monitoring research studies conducted by the data science team. He said that the team had freedom to try nearly any test it desired, so long as it didn't interfere with the user experience. He added that the sheer mass of the experiment's subjects was at times difficult to really comprehend, numbering in the hundreds of thousands of users. As he put it, "You get a little desensitized to it."

Forbes points out that the "research" part of the User Data policy was not added until May 2012, while the research was conducted in January of 2012.

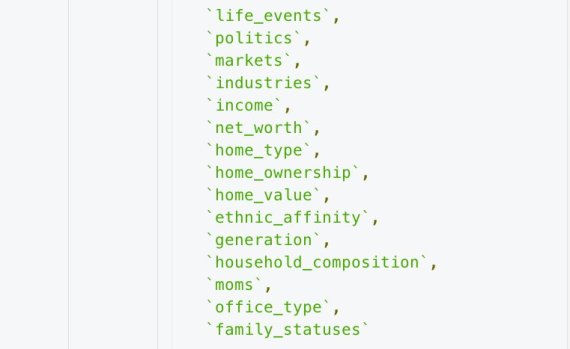

Facebook data is potentially available to government agencies.

Facebook has spoken out about U.S. government information requests it considers unconstitutional. Facebook's Deputy General Counsel Chris Sonderby published a statement last month about the site's legal fight regarding one such search warrant, in which the government requested nearly all data on 381 Facebook users. Only 62 of those searched were charged, in a disability fraud case.

He noted that, "We regularly push back on requests that are vague or overly broad."

But Facebook's second Global Government Requests Report showed that when the U.S. government asks, Facebook hands over at least some user data in more than 80 percent of cases:

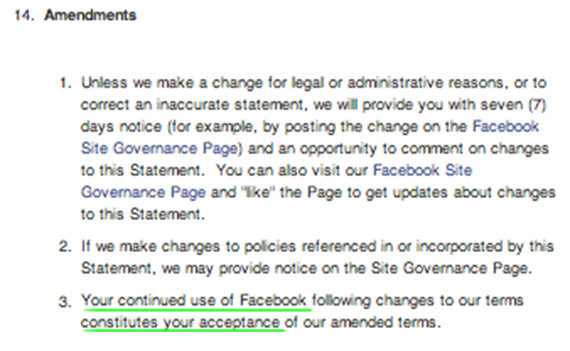

And if you actually think you know what you've agreed to, remember that Facebook maintains the right to change its mind about user conditions at any time.

Basically, if you're still using Facebook, you're agreeing.

After the site unveiled its new, more aggressive approach to targeted advertising in June, a Facebook spokesman told the Wall Street Journal, "We routinely discuss product and policy updates with our regulators -- the FTC and the Irish DPC -- and this time is no different. While we are not required to notify nor seek approval from regulators before we make changes, we do keep them informed and answer any questions they may have."

It's clear that the meaning of privacy is changing drastically in the digital age. While Facebook may be one of the agents of change in drafting a new definition, it's certainly not the only one. As standards of privacy continue to morph, knowledge remains your best weapon in protecting yourself and your information. We recommend checking out the documentary "Terms And Conditions May Apply" for an in-depth look at privacy in the digital age. Common Sense Media also offers helpful guidelines for protecting your and your children's privacy online.