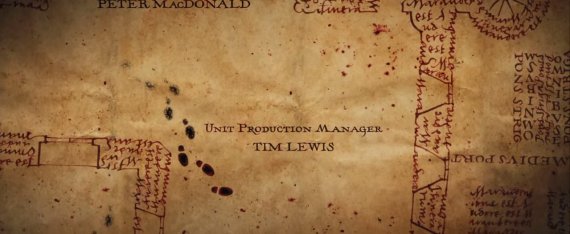

At the end of "Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban," hidden in an alcove in the far left corner of the Marauder's Map, are what many dedicated Potterheads have presumed to be two students hooking up, despite the adapted film's PG rating.

For those unlearned in the magic of the Potter universe, the Marauder's Map shows the location of everyone within the Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry with little footsteps. Usually, a glance at the map will simply show various pairs of footsteps walking or loitering, but given the position of these two specific pairs of feet and a half-second wiggle, it's easy to wonder if these two students are managing a bit of mischief.

The potentially scandalous moment (seen above) occurs at the movie's end credits, which was sort of an unprecedentedly long and impressive sequence for its time. After following a long rabbit hole of people who worked on the varying aspects of visual effects for the movie and, more specifically, the Marauder's Map, The Huffington Post finally found Rus Wetherell, the man in charge of designing the sequence and those mysterious footsteps.

Was this fleeting moment truly a "sex scene" or was the true intent less than definite? Were the footsteps snuck in without someone's knowledge or did the Academy Award-winning director of "Prisoner of Azkaban," Alfonso Cuarón, insist on their inclusion in the final cut? Wetherell has the answers...

The idea for the footprints in the corner was a "behind the bike shed" moment that "wasn't meant to be any particular character from the movie." That said, Wetherell suggested that it could have been an extension of Potter and Chang's kissing moment. Although that doesn't end up happening until "Order of the Phoenix," the third movie got some flack for essentially removing Potter's growing crush on Chang, so maybe this was a way to make up for that?

"Maybe it was meant to be Harry, but we've all been kids, we've all been in school and stuff ... It was just a sort of little peck on the cheek," assured Wetherell.

In Wetherell's mind, the couple's feet "are in an embrace" and "not having sex as everyone says." The addition of the feet ended up making the final movie because, when director Alfonso Cuarón spotted the moment, he started laughing and "just went nuts." As Wetherell explained, Cuarón liked that "it was just something there that was amusing for the adults in the audience and kids wouldn't really understand."

Originally, Wetherell suggested doing more with the feet, but Cuarón told him no, just leave them and move on. "It was just a little light heartedness and bringing a bit of a smile to people," said Wetherell. And so the moment for adults -- that is totally not a "sex scene" -- was left in the PG movie.

The "embrace" came out of a late night when Wetherell "was going a bit out of [his] mind." He was trying to get down "loads and loads of footprints" and then he "chucked a couple there and it made [him] laugh at 4 a.m. after doing sort of 20 days back to back."

"There was an alcove in the artwork, it was kind of like an opportunity to have a couple of students hiding in there. So I just threw a couple of feet down," said Wetherell.

As the process was going along, Wetherell inserted many different footsteps as sort of placeholders with the intent of going back to them and at least "embellishing and improving." However, with the demand of the production and deadlines, Wetherell admitted there were a few that he simply never got back to and, along with Cuarón's instructions, the sneaky embrace survived.

Cuarón was closely involved with Wetherell's work and "saw about every aspect of the movie down to each of the individual sets of footprints." Cuarón's enthusiasm for how the end credits was going encouraged Wetherell to keep adding "more and more and more" which ended up leading to the inclusion of the embrace.

Originally, the Marauder's Map for the main film was created by an artistic team consisting of Miraphora Mina and Eduardo Lima, and from this outline, the company Cinesite enlisted visual effects artist Evan Davies to create the dissolving footsteps. All of these things -- including the physical prop map -- were then handed to Wetherell to develop the elaborate footstep patterns for the credits sequence essentially by himself.

This ended up becoming an elaborate process due to the tech at the time and Wetherell's relative newness to the field, causing an "incredibly intensive period" that he recalled lasted about five to six weeks of 20-hour days. At about 11 minutes long, the end sequence was the longest of its kind at the time and, including drafts, Wetherell had to create thousands of different footsteps with different gaits and speeds and direction patterns to complete it.

The custom map was made on parchment and then shot with a camera movement that had to be calculated just right as to keep everyone's name on screen the right amount of time. Often more names would be added to the credits list and then the whole process would have to be reworked. There were about 100 different pieces of artwork that had to be placed together and so just a slight tweak could require a serious reconfiguring.

On top of this, Wetherell had only been given a visual effects element for one foot and so to make it not seem like a boring clone job over the lengthy end credits, he had to create many different steps. As Wetherell explained, the job was "trying to give the illusion that all these footsteps are actually different characters doing different things at different times," such as hopping or skipping or jumping or something more nefarious.

Throughout the end credits sequence, the footprints have many unique moments, like when they turn into animal prints around the ILM motion picture visual effects company name or, of course, the embrace. One such elaborate moment involves a "Stink Bomb Store," when there's a mini-explosion and then all the feet run out.

But Wetherell doesn't consider these moments the true Easter eggs -- or hidden moments -- of his work, as he hid even more hard to spot moments in the credits. Apparently, there are various things hidden in the Latin text that makes up the walls of the Marauder's Map that, according to Wetherell, are "very well hidden."

Although he wouldn't reveal those hidden bits are, Wetherell did at least say that some of the words hidden are simply production credits that didn't get a prominent inclusion in the list of names -- including his own. It was the company policy of his employer, Capital FX, to not have credits on any of the work and so he figured he might as well get his name in there somewhere. This, incidentally, seems to be a common practice with visual artists. Davies, who first made the footstep animation, revealed to HuffPost he'd done the same thing and got his logo "into the Daily Prophet sequence."

Wetherell said that he felt there were people in the production team who essentially had nervous breakdowns working on this thing and deserved to get at least some sort of nod and onscreen thanks.

"End rollers were quite often a sort of a last thought," said Wetherell, explaining the context of the job he took on now over a decade ago. "It was just the Wild West back then." The intense production schedule came out of the fact that nothing like this end credits sequence had been attempted before and what "really started off as a simple task" ended up in hindsight being a job that should "probably have taken a team of five people," according to Wetherell.

Even so, Wetherell now takes pride in the fact that television broadcasts will regularly still play the movie all the way through to the end credits, and that colleagues, people in the industry and members of Warner Brothers, congratulated the effort. Occasionally old work friends will joke and reminisce about the unexpected "intensity of the project, but also, the sort of mold it broke as far as end credits."

Wetherell's son and daughter still aren't quite old enough to appreciate Harry Potter, but he's excited for the moment he can show the final can of the end credits Cuarón was shown, that he has kept over all these years. In his mind, it was the most demanding job in his career and he has pride in irritating the television networks a bit into forcing them to show his work.

During that production, Wetherell would take the 35 millimeter print under his arm to the test screenings in London and try hard each time to simply not "disappoint" Cuarón. This work ethic ended up paying off and led to later jobs on other Cuarón projects, including the Oscar nominated "Children of Men."

As far as the other Easter eggs besides the embrace, Wetherell believes they may just stay hidden forever. "We've gone 10 years ... you're the first person to have contacted me about the piece. And I haven't done much searching online, but no one appears to have found anything in there," said Wetherell. "Who knows, maybe in another 10 years it will still be there."