When was the last time you gave serious thought to a drinking fountain? Maybe it was in elementary school, when they were the only way to wet your whistle. Or maybe never. That would be perfectly understandable. They seem boring!

But they're not. Far from it.

About a month ago, I started looking into the history of water fountains -- basically on a whim. (I came across some interesting facts about them while researching my massive story about public drinking a year ago, because the search queries overlapped, and thought I'd follow up.) But once I started digging, I quickly became obsessed. It turns out the history of drinking fountains is much crazier than I could have imagined. Brace yourselves.

Opening Of The First Public Drinking Fountain For The Metropolis (Photo by Liszt Collection/Heritage Images/Getty Images)

Opening Of The First Public Drinking Fountain For The Metropolis (Photo by Liszt Collection/Heritage Images/Getty Images)

The history of fountains stretches back thousands of years, to ancient Crete and Greece, where fountains were fundamental building blocks of early urban life. People came to some and filled up jugs of water, while others were basically public sculptures that incorporated moving water. But it wasn't until the second half of the 19th century that anyone thought of building a fountain specifically for individual people to drink water on the go. In 1859, a group of wealthy Londoners, responding to outbreaks of cholera spread by filthy water, formed a group called the Metropolitan Drinking Fountain Association, dedicated to the construction of public drinking fountains in the city using private funds. At the time, many poor people got their water from private companies that hauled it directly from the Thames, which was increasingly polluted by human waste and other effluvia of city life. Free, filtered water was a major boon.

The Metropolitan Drinking Fountain Association opened its first drinking fountain in April 1859 -- and thousands gathered to watch it be turned on. The drinking fountain was so popular that the association opened hundreds more across the U.K. in the decades that followed. By 1879, there were almost 800 drinking fountains in London alone. Many of the fountains also included accommodations for watering horses, cows and dogs. In 1867, the name of the group was changed to the Metropolitan Drinking Fountain and Cattle Trough Association to acknowledge this part of the mission.

Tinted lithograph by C. J. Culliford, showing a man and woman beside a wall-mounted fountain offering 'filtered New River' water. The men in the background mock the woman for daintily wiping the tin cup before drinking from it. (Photo by SSPL/Getty Images)

Tinted lithograph by C. J. Culliford, showing a man and woman beside a wall-mounted fountain offering 'filtered New River' water. The men in the background mock the woman for daintily wiping the tin cup before drinking from it. (Photo by SSPL/Getty Images)

Though the look of the large edifice housing fountains varied across the decades and from place to place, the central mechanism was remarkably consistent. It featured three main components: A spigot that sent out a continual stream of fresh water, a basin for collecting the water, and a metal cup, attached by chain to the edifice, that was kept in the basin of water. Thirsty passers-by would grab the metal cup and drink it dry, then put it back into the basin of water.

That's right. Everyone used the same cup. Day in and day out. Although germ theory had, by the 1860s, started to gain acceptance, everyone assumed that the water flowing over the cup would keep it clean. And no one thought that germs could live on a metal cup. They were wrong, of course, but it would take them many decades to realize it. We'll get back to that later.

circa 1860: A street scene in New York. The New York Times building is on the left and the only traffic is horse-drawn carts. (Photo by Henry Guttmann/Getty Images)

circa 1860: A street scene in New York. The New York Times building is on the left and the only traffic is horse-drawn carts. (Photo by Henry Guttmann/Getty Images)

Across the pond, many New Yorkers in the 1850s also wanted drinking fountains. The city gained access to a consistent source of fresh water in 1842, when the Croton Aqueduct started bringing water from northern Westchester County. But it took decades for many poor and working-class people to get connections to the distributing reservoir of the Croton, which meant that many continued to rely on polluted wells and cisterns. Cholera and other waterborne diseases continued to be serious problems well into the 1850s.

Moreover, even for those with tap water in their homes or apartment buildings, there was almost no way to get good drinking water out of the home, in the course of people's days. That encouraged urban laborers and flaneurs to stop into saloons and grog houses when they felt thirsty.

For all these reasons, The New York Times began regularly editorializing for the installation of drinking fountains almost as soon as the paper was founded in 1851. In one opinion piece from June 1855, for example, the paper wrote, "We are not aware of there being a single public fountain, in this City of Fountains, as it has been absurdly called, at which a weary man may slake his thirst."

View of the new drinking fountain at Madison Avenue and 23rd Street in New York, circa 1881. (Photo by Stock Montage/Getty Images)

View of the new drinking fountain at Madison Avenue and 23rd Street in New York, circa 1881. (Photo by Stock Montage/Getty Images)

New York City heeded The New York Times' call on June 10, 1859, when the city's first public drinking fountain was installed in City Hall Park downtown. The Times reported that "crowds" gathered to watch it get turned on, and added, "It is to be hoped that public drinking fountains in this city will soon be so numerous that they cease to be a subject of remark." Just 10 days after it was installed, City Council voted down a bill that would have provided funding for 50 more public drinking fountains. In a withering article, The New York Times chalked the decision up to financial interests, noting that "fountains have no votes, and free fountains can buy none. Grog-shops, on the contrary [...] are notoriously prolific of votes."

It wasn't until around 1880 that water fountains really proliferated. Wealthy residents started underwriting their construction, and often emblazoned their name across the fountains. Yet well into the 1880s, new fountains were considered significant enough to warrant news stories in major newspapers. And large crowds would gather to watch them be turned on. In 1881, The New York Times wrote that a thousand people were present at the opening of the water fountain in Union Square.

Though the donation of money for fountain-building was, at the end of the 19th century, a broadly popular activity for many wealthy people of all persuasions, the most active contingent was temperance activists. They believed that giving urban residents easy access to clean, cold drinking water would discourage them from drinking the more widely available alcohol throughout the day. Temperance advocacy groups, many composed of individuals of average means, would pool their money to build fountains in towns and cities across the country. They would often have words like "TEMPERANCE" emblazoned in large letters across the fountains. Many, including the one pictured above, still stand today.

This 1930 photo shows French cyclists availing themselves of free drinking water at one of the dozens of so-called Wallace fountains that were built around Paris using designs and money donated by British philanthropist Sir Richard Wallace after the Franco-Prussian War and the Paris Commune devastated the city's drinking water infrastructure. (Photo by Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone via Getty Images)

This 1930 photo shows French cyclists availing themselves of free drinking water at one of the dozens of so-called Wallace fountains that were built around Paris using designs and money donated by British philanthropist Sir Richard Wallace after the Franco-Prussian War and the Paris Commune devastated the city's drinking water infrastructure. (Photo by Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone via Getty Images)

Remember how people drank from all these early drinking fountains using metal cups? Around the turn of the 20th century, health advocates realized that was a terrible idea. The first major figure to speak out against the so-called common cup was Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor William T. Sedgwick, but other public health thinkers followed over the next decade, publishing studies demonstrating that common cups were capable of spreading disease. "Ban The Cup" campaigns convinced almost every state to pass laws between 1909 and 1912 making common cups illegal.

The proprietors of public drinking fountains sought alternate ways of dispensing water. One popular solution was to replace the permanent cup with disposable paper cups, which were invented in 1907. That way, water fountain patrons could still enjoy the same satisfying drinking process they always had, without spreading disease.

More often, though, they installed what were then called "sanitary drinking fountains," which required no cup at all. Though these had existed at least since 1900, they only became widespread after the "Ban the Cup" movement took hold. Sanitary drinking fountains came in various shapes and sizes, but most early ones featured a spigot that shot a jet of water straight into the air, like a miniature geyser.

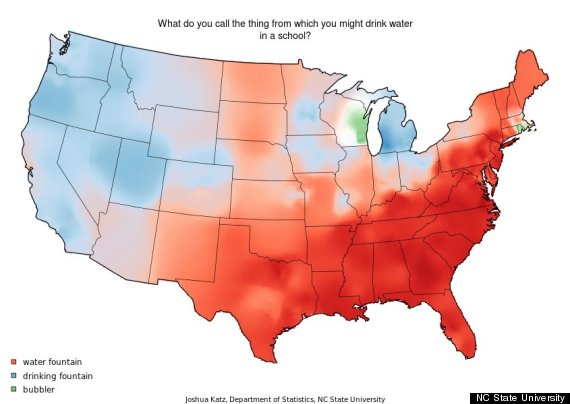

Most people in the United States today refer to them as "drinking fountains" or "water fountains" -- the two are more or less interchangeable. But when cupless drinking fountains first came into being, some people called them "bubblers" to differentiate them from the old, cup-dependent style.

As you can see in the map above, people in Wisconsin still often refer to the devices as "bubblers," as, apparently, do in Rhode Island and Australia. It's not entirely clear why. A commonly-repeated story says that the Wisconsin-based Kohler Co. invented sanitary drinking fountains at the end of the 19th century and called them "bubblers," and that state pride has kept the word alive. But a recent story in the Sheboygan Press convincingly disproved this etymology.

Public health experts quickly realized that eliminating common cups did not eliminate the risk of transferring germs through drinking fountains. The vertical-jet style of drinking fountain encouraged many people, eager to imbibe the full draught of water they were used to, to put their lips directly on top of the spigot, which was almost as unsanitary as using a common cup. Fountain engineers spent years trying to come up with solutions. Many of them attached metal cages to the top of the spigot, in an effort to keep people's lips off the nozzle, but this was only partially effective, because some people just started putting their lips on the mouth guards instead. Just like people in fictional Pawnee, Indiana, on the TV show "Parks and Rec" do to this day.

Two college students drink from a slanted-jet style drinking fountain.

Two college students drink from a slanted-jet style drinking fountain.

Ultimately, the problems with vertical jets of water inspired plumbing engineers to settle on another solution entirely: slanted jets. Instead of aiming the spigots straight up, they aimed them at approximately a 45-degree angle, and then affixed a mouthguard to the spigot to prevent people from putting their lips directly on it. This method seems largely to have solved the issue of germ transfer. The design has persisted to this day.

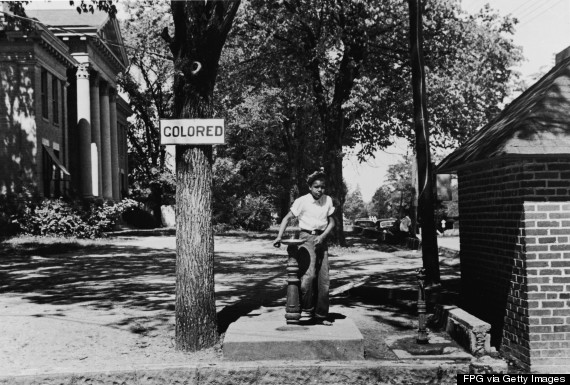

A young boy drinks from the "colored" water fountain on the county courthouse lawn, Hallifax, North Carolina, April 1938. (Photo by John Vacha/FPG/Getty Images)

A young boy drinks from the "colored" water fountain on the county courthouse lawn, Hallifax, North Carolina, April 1938. (Photo by John Vacha/FPG/Getty Images)

By the 1950s, public drinking fountains were everywhere, setting the stage for them to become a potent focus for debates about the structure of public life. Under Jim Crow laws, drinking fountains were one of many public amenities segregated by race. For black people living in the South, they became a powerful symbol of the pervasiveness of racist laws. Even though the desegregation of drinking fountains was never considered as important as, say, the desegregation of schools, it nonetheless became a powerful symbol in the struggle for equality.

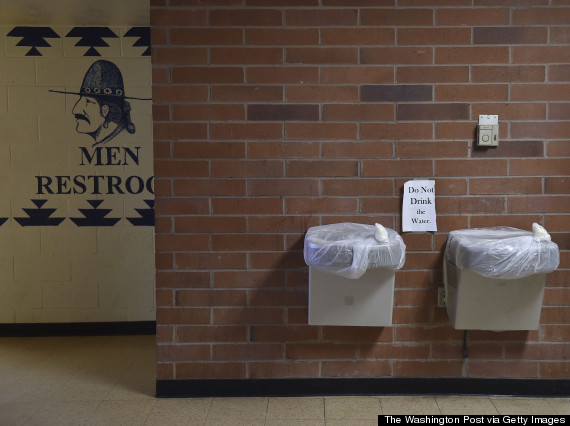

School water fountains like these ones came under harsh scrutiny starting in the late '80s for lead poisoning. (Photo by Ricky Carioti/The Washington Post via Getty Images)

School water fountains like these ones came under harsh scrutiny starting in the late '80s for lead poisoning. (Photo by Ricky Carioti/The Washington Post via Getty Images)

Some experts have been concerned about the possible health effects of lead for centuries, but it wasn't until the 1970s that lead poisoning became a national fixation, and the Environmental Protection Agency started taking serious measures to limit Americans' exposure to the metal.

As part of that effort, EPA employees tested water from school drinking fountains for lead in 1986 -- and what they found was shocking. Many school drinking fountains were dispensing water that contained dangerously high levels of lead, because the design of the fountains included some lead components. Local investigations confirmed that the issue was widespread. Congress conducted hearings on the issue, and water fountain manufacturers rushed to develop new designs that eliminated the risk, but the damage to the reputation of drinking fountains was done.

Controversies such as the lead poisoning scare may have dented the popularity of drinking fountains, making them vulnerable to competition -- which finally came, in the 1980s, in the form of bottled water. Starting in the late '80s, American consumption of bottled water skyrocketed, rising from about seven gallons per American in 1987 to 30 gallons per American in 2007. MacArthur fellow Peter Gleick argued, in his landmark history Bottled and Sold, that the rise of bottled water was instrumental in the declining popularity of drinking fountains. There are a host of reasons for that: People think bottled water tastes better, for one, and they don't like sipping from the slanted jets of drinking fountains. Today, these fountains are still a fixture of public buildings because building codes require them. But they largely sit forlorn, at least outside elementary schools.

Children from St. Vincent Roman Catholic primary school use a new public drinking fountain in Hyde Park on Sept. 23, 2009, in London. It is hoped that the drinking fountain, the first to be unveiled in 30 years by Royal Parks Foundation and The Royal Parks, will reduce the use of plastic bottles. (Photo by Dan Kitwood/Getty Images)

Children from St. Vincent Roman Catholic primary school use a new public drinking fountain in Hyde Park on Sept. 23, 2009, in London. It is hoped that the drinking fountain, the first to be unveiled in 30 years by Royal Parks Foundation and The Royal Parks, will reduce the use of plastic bottles. (Photo by Dan Kitwood/Getty Images)

In recent years, various forces -- including Peter Gleick, not to mention the EPA -- have tried to reverse the movement against drinking fountains. They argue that the consumption of bottled water is wasteful, on several levels, and that we should embrace drinking fountains as a more sustainable, economic alternative. Some have proposed installing new, better drinking fountains, such as the one pictured above in London's Hyde Park, as a way to encourage their use. There's even an app that helps people find drinking fountains in public places. It's too early to say whether these efforts will succeed. But if the last 150 years have shown anything, it's that drinking fountains are resilient.