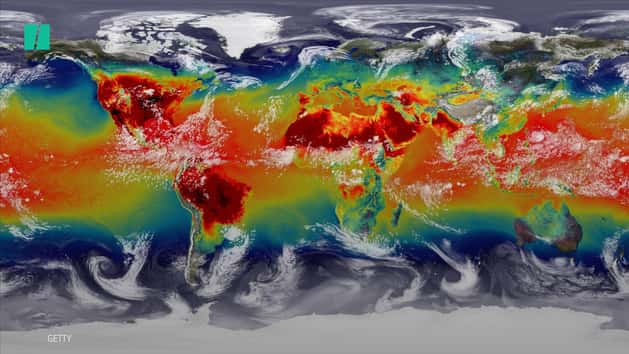

The world is rapidly running out of time to scale back greenhouse gas emissions, dimming hopes of keeping global warming within 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) above pre-industrial levels, beyond which catastrophic planetary changes are forecast.

That assessment comes from a sobering new report issued by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, or IPCC, the leading United Nations consortium of researchers studying the speed and scope of human-caused temperature rise.

“This is one of the most important reports ever produced by the IPCC, and certainly one of the most needed,” Hoesung Lee, the chair of the body, said at a press conference in South Korea on Monday. “Climate change is already affecting people, livelihood and ecosystems all around the world.”

He continued: “Every bit of warming matters.”

The report ― authored by 91 researchers and editors from 40 countries citing more than 6,000 scientific references and released Sunday night following a summit in Incheon, South Korea ― details how difficult it will be to keep the planet from warming beyond the 1.5-degree target, considered the aspirational goal of the 2015 Paris climate accord.

To meet that target, the world would need to aggressively phase out fossil fuels to meet net-zero emissions by mid-century, and remove carbon dioxide and other heat-trapping gases out of the atmosphere from then on, according to the IPCC. More immediately, emissions would have to drop by about 45 percent below 2010 levels by 2030.

At 1.5 degrees of warming, small islands and major coastal metropoles like New York City, Mumbai and Jakarta risk disastrous flooding without costly sea barriers.

Yet carbon emissions began growing again last year after a three-year plateau as fossil-fuel emissions hit an all-time high. Emissions have quadrupled since 1960, and globally the last four years have been the warmest four on record, according to an international report released in August.

“I see so little evidence that 1.5 is achievable that I think that the main impact of a focus on 1.5 will be to demoralize people,” Andrew Dessler, a climate scientist at Texas A&M University, said in an email Sunday.

Under President Donald Trump, the United States ― the world’s biggest emitter of greenhouse gases per capita ― is shredding every major policy to reduce its carbon footprint. The U.S. has also stopped giving money to a fund that helps poorer countries invest in clean energy and adapt to a warming world.

In a surprise move late last year, the White House signed off on a lengthy report by dozens of federal agencies that concluded the planet has entered the warmest period “in the history of modern civilization,” with global average air temperatures having increased by 1 degree Celsius (1.8 degrees Fahrenheit) over the last 115 years. And buried in a report released in August, the White House said it assumes a cataclysmic 4 degrees Celsius (or 7 degrees Fahrenheit) of warming is inevitable by the end of the century.

The IPCC said the report did not consider the United States’ plan to withdraw from the Paris Agreement because there was no literature analyzing that factor.

“What we have done is said what the countries of the world collectively need to do, we don’t go specifically, we never go into looking into individual countries,” Professor Jim Skea, co-chair of the IPCC’s Working Group III, said during the press conference. “We have sent a clear signal to the collectivity of countries. The U.S. is part of that.”

Emissions from China, the world’s top national source of carbon dioxide in raw numbers, are set to grow in 2018 at their fastest clip in seven years. Meanwhile, new satellite images show coal plants the country promised to cancel continuing construction.

The IPCC report determines with “high confidence” that if humans continue to pump greenhouse gases into the atmosphere at the current rate, the global mean temperature ― which is already 1 degree Celsius above pre-industrial levels ― will likely rise to the 1.5-degree mark sometime between 2030 and 2052.

Ways to reverse carbon dioxide emissions include maintaining forests and better managing soil, which naturally recycles CO2. But the IPCC authors said nascent technologies to suck carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere are likely to play a necessary role.

“We should be doing everything we can,” said Natalie Mahowald, a climate scientist at Cornell University and lead author of the report’s first chapter. “That’s the main thing about getting to 1.5 is just how aggressively we have to act in every different sector of our society.”

Slashing so-called super pollutants ― greenhouse gases far more potent, but less prevalent, than carbon dioxide ― could help slow the rate of near-term warming.

Methane, the main component in natural gas, is 86 times more powerful than CO2 over 20 years in the atmosphere. The refrigeration and air-conditioning chemicals called hydrofluorocarbons, or HFCs, are roughly 1,000 to 3,000 times more potent at trapping heat than CO2. Black carbon ― sooty particulate matter emitted by the incomplete combustion of fossil fuels ― traps 460 to 1,500 times more heat than CO2. Yet regulations on those pollutants remain nascent or nonexistent, with the Trump administration making an effort to roll back rules on the first two.

There’s “still space for natural gas in the mix” if it includes technology to capture carbon emissions, Skea said. But “coal will have to be reduced very, very substantially by the middle of the century.”

Scientists say that allowing warming of 1.5 degrees Celsius would spur dramatic consequences. Sea levels will continue to rise beyond 2100, even if warming is limited to 1.5 degrees, threatening coastal ecosystems and infrastructure. Flooding, drought and extreme weather events will wreak havoc on communities around the globe. Many species will continue to be driven toward extinction and marine ecosystems could face “irreversible loss.”

Warming of 2 degrees exacerbates those dangers significantly, according to the report. By that point, global sea levels are projected to rise 10 centimeters higher. The Arctic Ocean would be free of sea ice in the summers at least once per decade instead of once per century, as is forecast under a 1.5 degrees scenario. Coral reefs, which have been devastated in recent years by mass bleaching events, will likely experience widespread die-offs. Reefs could decline by between 70 and 90 percent with 1.5 degrees of warming, and by 99 percent at 2 degrees.

The world’s most vulnerable populations are likely to be hardest hit, with poverty forecast to rise alongside warming. Keeping that warming to the 1.5-degree mark could prevent hundreds of millions of people from being exposed to climate-related risks and susceptible to poverty by mid-century, according to the report.

“We’re looking at a century that will face challenges with food and water security,” Kristie Ebi, a University of Washington health researcher and lead author of the report’s third chapter, said on a press call Sunday. “Those challenges will be much larger at 1.5 degrees C than they are today and they’ll be even more difficult at 2 degrees C.”

Nick Visser contributed reporting.