Hiyasu Uraki points to the white, fluffy seal on the table in front of us. “You should also sing to it,” she instructs me. As I start singing, the seal looks up, blinks at me and gently coos. A smile spreads across Uraki’s face.

This is Paro, a robotic seal at Tokyo’s Silver Wing care facility aimed at providing residents like Uraki with therapy and social interactions. Uraki won’t give her precise age; she’ll only say 80-something. “She often says that, but actually she’s 99 years old,” the care facility manager, Yukari Sekigichi, interjects, and we all share a laugh.

Residents often talk to the seals ― there were four on the table in front of us ― about everyday events such as the weather. “They also serve as a starting point for conversations between residents,” Sekigichi explains.

Robots like Paro, designed to provide companionship, are part of a range of technologies that have emerged in Japan to combat rising loneliness.

Loneliness is a big issue in the country of 127 million, which has the oldest population in the world. Statistics focusing on loneliness in Japan are scarce, but an estimated 6.24 million Japanese people over 65, and a total of 18.4 million adults ― twice as many as 30 years ago ― live alone. By 2040, 40 percent of the country’s inhabitants will be solo dwellers.

The consequence of this has been a rise in kodokushi ― people dying alone and remaining undiscovered for long periods of time ― especially among younger generations. One estimate is that there are 30,000 of these lonely deaths a year, but companies that clean apartments when kodokushi are discovered say the number could be two or three times higher.

Amid this rising social phenomenon ― a public health concern linked to depression, dementia and heart disease ― businesses see an opportunity through technology. Robots like Paro can be programmed to fill social gaps that can lead to loneliness.

The Scourge Of Loneliness

In her book, Sekai Ichi Kodoku na Nihon no Ojisan (Japan’s Old Men are the World’s Loneliest), psychologist Junko Okamoto dubs Japan the “loneliness superpower.” She told the Financial Times: “Society is not doing enough to address loneliness and people don’t want to admit how unhappy they are.”

Modern life in Japan, which has had its foot to the economic pedal for decades, may have come at a cost: the unpicking of traditional social structures. “The increase in loneliness, and lonely deaths, is partly tied to traditional family structures falling apart,” says Masaki Ichinose, a professor at the Center for Life and Death Studies at the University of Tokyo.

Western-style nuclear families have taken the place of traditional, multi-generational households, which used to serve as a social safety net for especially the elderly, says Ichinose.

Many workers face punishing hours, fueling the phenomenon of karōshi, or death by overwork. At the less extreme end of the spectrum, grueling work schedules leave people with little time to find partners and have children.

Life can be equally challenging, if not more so, for the growing slice of the population unable to find permanent jobs. A prolonged economic slump means that while unemployment is low, steady good-paying jobs remain hard to come by. Many people end up working several jobs to make ends meet, allowing little time to socialize.

For some people in Japan, the pressures have led them to withdraw from society altogether. Professor Takahiro Kato at Kyushu University’s Department of Neuropsychiatry studies loneliness and hikikomori (or shut-ins), the trend for people to live in isolation for a year or more. Kato points out that data is sparse, but a study by the Japanese government showed there to be 500,000 hikikomori aged 16 to 39. “The initial findings before 2000 were that it was mostly young people. However, we have seen a marked increase in hikikomori amongst middle-aged and old people,” he says.

The Technological Solution

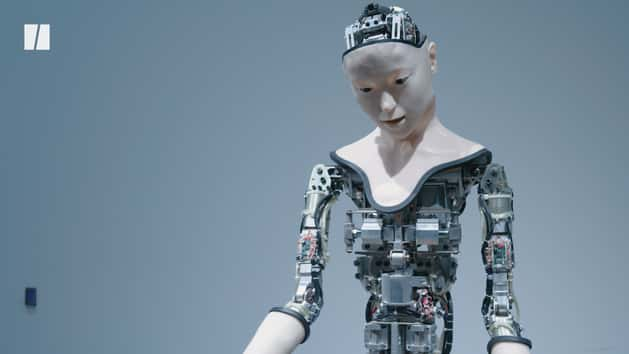

For Japan, part of the answer to the growing loneliness is technology ― and that technology is becoming increasingly life-like.

Sony’s Aibo robot dogs, for example, re-launched by maker Sony after being retired in 2006, inspire such an emotional bond with their owners that some hold funerals when the robotic pets stop working.

Tech giant Softbank Robotics produces the Pepper robot, a humanoid designed to provide companionship, which some have taken to integrating into their family as substitute children or grandchildren. At Silver Wing care facility, Pepper is in charge of the midday exercise session.

Perhaps one of the best examples of how the robots offer companionship is the Telenoid R1. Like others, its minimalistic design is meant to make it easier for users to project faces of, for example, family members when they speak with it.

A whole industry also has sprung up to provide company to younger customers, primarily men, who aren’t having human relationships. (A 2013 study found that 30 percent of Japanese men in their 20s and 30s had never dated.) Gatebox has developed the anime-inspired VR-companion, tailored toward younger men who, due to long work hours or other reasons, prefer the company of a virtual partner.

Japanese startup Couger is developing an AI-powered virtual assistant that can follow a user around, and move seamlessly from device to device. Company founder Atsushi Ishii says part of the goal is creating a system that people can relate to on a personal level, perhaps making them feel less lonely.

“Humans and AI-powered technology, like robots and virtual assistants, should have a relationship like friends. One that is built on trust and one where people can perhaps open up to ― and build a social relation to ― the technological solution easier than they can to a person,” Ishii says.

Outsourcing Empathy

This technology does seem to work, says Takanori Shibata, a professor at Japan’s National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology. “Studies showed that interaction with Paro improved loneliness significantly,” says Shibata.

Clinical psychologist Puihan Joyce Chao, who treats many people suffering from extreme loneliness, agrees technology can provide part of the answer, but stresses the need to include a human element. Combating loneliness, she says, “starts on the individual level, and perhaps with a focus more on quality than quantity of connections and interactions. … Perhaps this is something that needs to be a focal point ― that we teach children and younger generations how to experience and be in the moment with the people around you.”

The idea of outsourcing the human need for care, contact and empathy to machines worries some. “Humans need human interaction; that is how we are evolved. We would want any technological solution like a friendship app to be used alongside offline connection,” says Laura Alcock-Ferguson, executive director of the Campaign to End Loneliness, a U.K.-based network.

Rising loneliness is not just a Japanese phenomenon. In the U.K., 500,000 elderly people say they go at least five days a week without seeing or speaking to anyone. The country is the world’s first to have a minister for loneliness. And in the U.S., a study in May 2018 showed that nearly half of Americans sometimes or always feel alone, and that loneliness was especially pronounced for young people.

Back at the Silver Wing care facility, manager Sekigichi, says at-home care would be preferable for the residents, but “the reality is that many elderly live alone and struggle to manage life on their own.” The robots help, she says. Relatives of some of the day care patients were amazed to see how much they interacted with the robots when they are at the center, compared with how little they are able to do in their homes. But Sekigichi, too, emphasizes the need for human contact: “Robots and technology can be used for some aspects, but we need humans to give full care to others.”

For more content and to be part of the “This New World”’ community, follow our Facebook page.

HuffPost’s “This New World” series is funded by Partners for a New Economy and the Kendeda Fund. All content is editorially independent, with no influence or input from the foundations. If you have an idea or tip for the editorial series, send an email to thisnewworld@huffpost.com