Hell had come to East Annie Street.

Opal Lee was 12 years old when her parents bought a home in the historic south side of Fort Worth, Texas. Her mom had it fixed up real neat. But the neighbors didn’t want a Black family living there. For three days, white residents swarmed the house and threw rocks at it. Lee’s parents sent her and her two brothers up the street a few blocks to be safe. They didn’t know what would happen.

By the evening of June 19, 1939, the crowd had grown to 500 people, according to reports. Lee’s father Otis Flake, who worked for Texas and Pacific Railway, had come home from work and pulled out his gun.

“If you bust a cap, we’ll let the mob have you,” an officer told him.

“Of course, my parents stayed as long as they could without getting hurt,” Lee, 93, told HuffPost. “And then, they left the house to them, and they burned the place, drug out the furniture, tore the place up.”

The police couldn’t control the rioters. The white mob destroyed the house.

Eighty years later, America has come a long way, but not far enough from that racial terror. Police and racist vigilantes point the blame right back at their targets, who were were sleeping, running, eating ice cream or minding their own business when they were killed. Today, the sting of racist violence and police brutality leaves a lasting scar in our consciousness. In May, that wound was reopened when a Minneapolis police officer pressed his knee into George Floyd’s neck for 8 minutes, 46 seconds, as Floyd pleaded “I can’t breathe,” and called out for his deceased mother. The officers were fired, and later, after thousands of people marched for justice in uprisings across the country, they were charged for his death.

But we haven’t stopped marching. Demands to defund the police; make workplaces diverse and inclusive; and rid our culture of racist stereotypes and statues ring in the streets and on social media.

Opal Lee’s family hardly talked about the fire. But this year, the retired teacher and community advocate has recalled this moment to remind Americans of the importance of Juneteenth, the official end of slavery in the United States, as the cry for freedom continues. She calls Juneteenth a “great unifier,” and said the fight for freedom includes good schools, housing, wages and health care for all people.

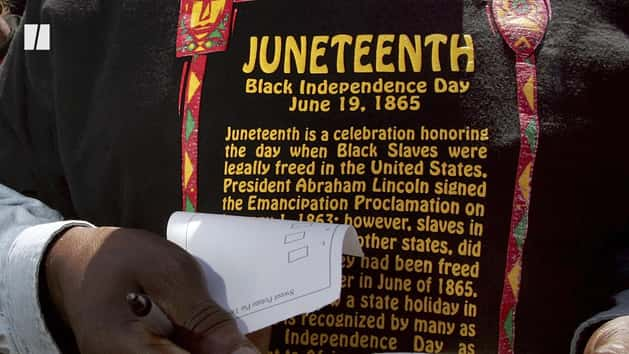

On June 19, 1865, Union General Gordon Granger arrived in Galveston, Texas, with 2,000 federal troops to read General Order No. 3 of the Emancipation Proclamation announcing that “all slaves are free.” The announcement came two months and 10 days after Robert E. Lee surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox — and two and a half years after Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation. Juneteenth became the official celebration of emancipation in Texas and eventually spread to other parts of the nation. Festivities often include parades, concerts and barbecues, complete with red food and drinks to symbolize Black resilience during slavery.

In Limestone County, where one of the oldest known celebrations of Juneteenth takes place, freedmen celebrated for days along the Navasota River, according to Doris Hollis Pemberton, author of “Juneteenth at Comanche Crossing.”

Throughout Reconstruction, Blacks purchased “emancipation grounds” to celebrate the holiday. Houston’s Emancipation Park was bought in 1872. In 1898, a group of freedmen purchased 30 acres of land, which was later named Booker T. Washington State Park, near Lake Mexia to celebrate the end of slavery in Texas. The 19th of June Organization was chartered in 1912 and received the title to 18 acres of the park. Commonly referred to as Comanche Crossing, that land has hosted Juneteenth festivities for nearly 150 years. “Come hell or high water, there will always be Juneteenth at Comanche Crossing,” the saying goes.

Though hell had come to Fort Worth in 1939, it never stopped Opal Lee from celebrating the holiday.

“I kept getting this feeling that I needed to be doing more than what I was doing,” Lee said. “We older people go home, get in our rocking chairs and wait for the Lord to call us. I decided He was going to have to catch me.”

Four years ago, Lee made headlines for her campaign to make Juneteenth a national holiday, in which she visited towns from Fort Worth to Washington, D.C., walking a few miles in each city, and attending Juneteenth festivities along the way. Lee eventually made it to Washington, D.C., in January 2017, after being invited to cities all across the country to share her message.

“I thought people would notice the little old lady in tennis shoes was walking and that we’d get Juneteenth, which is my passion, made a national holiday,” she said.

This year, Lee will walk 2.5 miles from the Fort Worth Convention Center to the Will Rogers Coliseum, leading a caravan of cars to celebrate Juneteenth. After the walk, food trucks from local vendors will line the area. There will be virtual concerts, seminars and other events livestreamed on Facebook. “Miss Juneteenth,” the debut feature film from Channing Godfrey Peoples, will premiere on demand. Peoples, who is also a native of Fort Worth, calls Lee the “Queen Mother of Juneteenth” and gave Lee a little cameo in her new film.

Last year, Lee started a Change.org petition to make the day a national holiday. Congress hasn’t designated a new holiday since 1983, but Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee wants to change that and plans to introduce legislation to mark Juneteenth.

“I cannot imagine this nation healing from the enormous and penetrating impact of race, racism and the history of slavery without officially acknowledging a day in the nation’s history that really speaks to freedom and independence for those who carried the burden of slavery,” Jackson Lee told HuffPost. “These past years of constant evidence of disparities in the African American community shows that the stain of slavery has not ended.”

If Opal Lee had it her way, Juneteenth would be the start of weeks celebrating freedom.

“I’m not one of those people who go all out for the Fourth of July, because I knew slaves weren’t free the Fourth of July,” she said. “If we could have something from the 19th to the 4th — oh, it would be fabulous. As the young people say, it would be off the chain.”

Miles Dotson, a 31-year-old Houston native, also envisions a longer celebration of Juneteenth. Along with Quinnton Harris and Brian Watson, the trio started Hella Juneteenth, an online hub of resources, events and community actions for Americans to learn about and celebrate the holiday. Their campaign has been a weeklong push to help more people understand the history behind Juneteenth.

The week has been dedicated to seven dimensions of the Black experience: the Black dollar, power and activism, archives and intersectionality, design, health and wellness, healing and joy. On Juneteenth itself, the organization will amplify community events and activities across the country on its social media platforms.

Hella Juneteenth is also pushing for companies to designate the day as a paid holiday, highlighting the work of Black people and businesses and ultimately working toward a national holiday. Several companies — including Nike, Twitter and Target — have announced that their companies will observe Juneteenth as a paid holiday this year.

“We want those who have influence and decision making power — whether it be in the corporate sphere, locally as a public official — to acknowledge this day is very critical and important to the country,” Dotson, who lives in Oakland, California, told HuffPost. “We think that there should be a holiday of purpose for Black Americans that allows for amplified economic opportunity to really pour into the communities, the businesses and the people.”

Dotson hopes the initiative will be a springboard to all things Juneteenth.

“The ultimate goal is just to bring Black Americans, our emancipation and continued dedication en route to freedom to the forefront and at the top of conversation as it needs to be,” he said. “Especially when we talk in terms of recent events when it comes to policing, and just the nature of how we feel safe in this country, and our ability to thrive economically involves and requires us being a part of that conversation.”

For Lee, being a part of the conversation also means encouraging people to vote. She remembers paying a $1.75 poll tax when she was first eligible to cast a ballot. Though America has come a long way since then, she knows the fight isn’t over.

“And none of us, I say, none of us are free until we’re all free,” Lee said. “Too many disparities that need to be addressed. We’re not free yet.”