Lucy Jones with Her Walking Stick, 1996 Oil on canvas 218.5 x 157 cm 86 x 61 3/4 in

In "Lucy Jones with Her Walking Stick," a woman wearing a green pullover sweatshirt and white pants stands before an ambiguous, unnatural purple backdrop. In one hand she clutches a black cane. Her pupils drift outward, her toes point inward. From the tilt in her head to the angles of her arms to the pop in her knee, Jones' body appears to exist on multiple axes, hunched and crunched like a wounded bird.

The arresting and unapologetic self-portrait is the work of 60-year-old painter Lucy Jones. Her current exhibition, "How did you get on this canvas?" is comprised of such striking portraits -- confrontational, awkward, defiant, other. As the show's title suggests, Jones is well aware of how rarely "women like her" are immortalized in paint. Women approaching and exceeding middle age, women who don't ooze overt sexuality, women battling physical and psychological impairments.

Jones presents herself as a foil to the classical nude odalisque, lounging sensually with politely averted eyes. Instead, she stares straight ahead, eyes vacant yet piercing, challenging the viewer to question her prerogative to exist on the canvas.

Jones studied painting at the Camberwell School of Art and the Royal College and had her first show in 1987 with an exhibition of landscapes at Flowers Gallery, where the Metropolitan Museum of Art acquired two of her paintings. Her rising success, however, was soon overshadowed by the conceptual art mania incited at a 1988 exhibition of Young British Artists, featuring individuals like Damien Hirst and Tracey Emin, who opted for theory and irony over beauty, and used anything but paint.

With some distance from the limelight, Jones continued to paint, racking up a collection of gripping self-portraits that capture the awkward joys and crushing pains of being alive.

Flushed, 2006 Watercolour pencil on paper 76 x 56 cm 30 x 22 1/4 in

Jones was born with cerebral palsy, which, according to the Mayo Clinic, is a disorder of movement, muscle tone or posture caused by an abnormality or disruption in brain development, usually before a child is born. Jones is also severely dyslexic, a condition that she believes has shaped her life more than her physical disability. However, without knowing about Jones' existing conditions, her self-portraits appeal to the challenges many of us, notably aging women, feel when confronting their reflections.

"Painting myself has helped me come to terms with all sorts of aspects of myself: being a woman, being a wife," Jones told The Huffington Post. "Looking at myself in the early work I was joining up two aspects: the very bad and the maybe okay. The frustrations that my dyslexia causes me are something that cannot be seen by others. There is a split between what people see -- the physical awkwardness, and what they cannot see –- such as dyslexia."

Due to her cerebral palsy, Jones literally suffers for her work too, struggling to find a position to paint in, kneeling for two or three hours at a time. Her artworks themselves, however, illuminate the more subtle side effects of living with a disability, such as reconciling her own understanding of self with the projected perceptions of outsiders. In her painting "A Handful of Tears," for example, the word "Fallen" is etched backwards next to Jones' likeness, a term seemingly ascribed to her by the world's gaze.

For years, Jones did not allow art critics to reveal or discuss her disabilities, fearing the fact would too greatly color the works themselves. "Even now it is something I am wary of," she said. "I am an artist, not a disabled artist. In my paintings, using me as a stand-in for being human, it became harder to discuss the painting without putting some explanation. I think my work speaks without my personal narrative attached to it as it covers the universal about how difficult it is to be human."

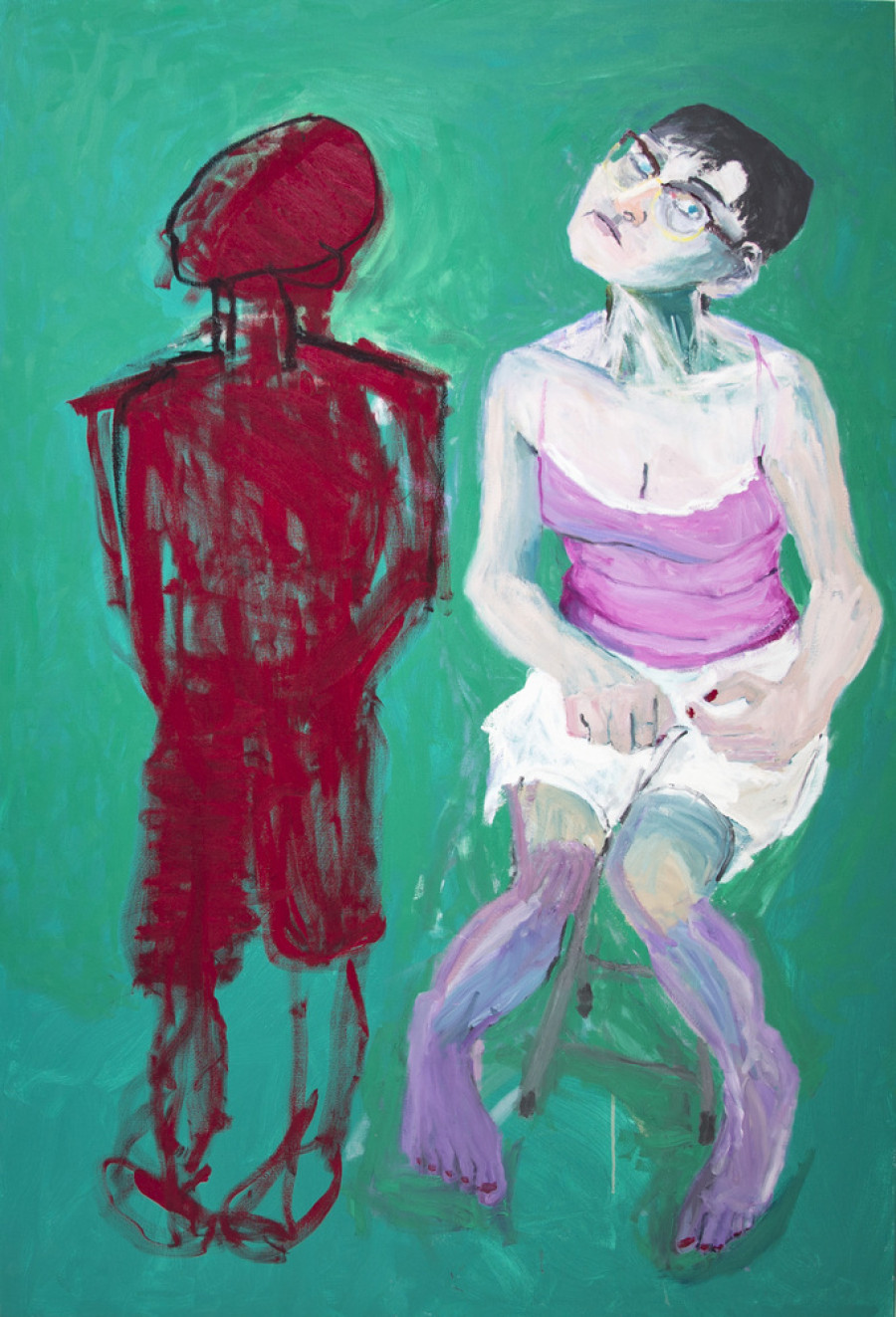

How did you get on this canvas?, 2013 Oil on canvas 180 x 120 cm 71 x 47 1/4 in

One distinctive element of Jones' paintings is their unabashed portrayal of sexuality. "I felt sexless (unlike Frida Kahlo)," Jones told the Financial Times about her ongoing battle with depression, echoing a sentiment endured by many women, so often expected to project a certain type of allure. In "Flushed," a watercolored Jones stares head on in a frilly black bra, her face blushing feverishly though refusing to break her gaze. The image challenges the dominant assumptions that older women, especially those with disabilities, are not desired nor are they lustful.

Jones' paintings, in the tradition of artists from Rembrandt to Lucian Freud, explore the awkward, ugly, salty and raw aspects of being alive. With pigment as her language, she visualizes the ways that otherness not only isolates us, but unifies us.

"My work draws on the physicality of my movements to make paintings which, to my mind, are translated through the physicality of paint, a medium I have used all my life," Jones concluded. "I see myself in a tradition of artists which include [Leon] Kossoff, [George] Baselitz and [Henri] Matisse, to name but a few. My work sits outside fashion, perhaps reflecting my feeling of being an outsider."

"How did you get on this canvas?" runs until May 9, 2015, at Flowers Gallery in New York City.