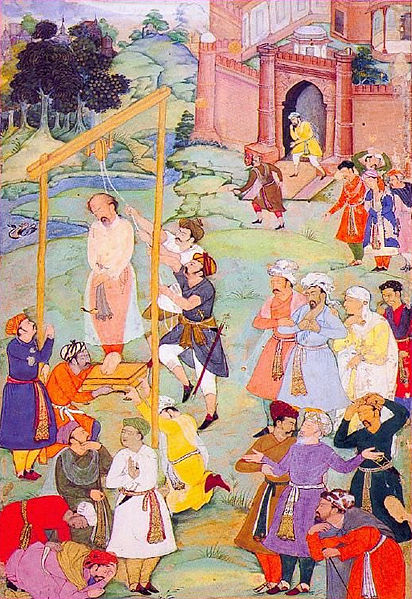

For some, Mansur al-Hallaj was a magician, a heretic and a lunatic, who publicly claimed to be one with the One and deserved to be executed for heresy. But to his sympathizers he was a Sufi saint, who was martyred almost 1,100 years ago, on March 26, 922, allegedly for his ecstatic utterance.

The legends surrounding Hallaj are many. Despite the 2,000 pages written by Louis Massignon, we still don't know much about him and there's no way to validate the claim that he ever uttered the words "ana'l-haqq" (I am the Truth), which many believe was the cause of his arrest, followed by nine-year long trial, leading to his public execution.

The are many fictional stories about him that ensued after his execution, including one told by Farid al-Din `Attar, who claims that Hallaj's one-time teacher, Junayd Baghdadi, changed his Sufi robes and put on a turban of a judge to condemn his disciple to death for heresy. But according to Carl Earnst, author of "Words of Ecstasy in Sufism," this is one of the many unfounded legends about Hallaj.

"The only problem with this story is that Junayd died in 910, and the execution took place in 922," he said. "We see another hostile account when Amr al-Makki was reciting the Qu'ran and the story goes that Hallaj said: 'I can write something like that.' And at that point Amr leaves him in disgust. And there are other stories that he looked at a woman, therefore, it was an illegal glance and he was condemned to die. So, people have come up with various romantic, imaginative explanations of his early life."

Since Hallaj's writings were burned to ashes, we can only conjure an image of the Sufi from his only surviving work, Tawasin, which is a collection of short pieces, of which the dialogue between Hallaj, Iblis (Satan) and the Prophet Moses, may God be pleased with him, is most famous.

A short poem that is said to be about Iblis describes the dilemma of Hallaj:

God threw a man into the sea, with his arms tied behind his back,

And said to him: careful! Careful! Or you'll get wet in the water!

(translated by Eric Schroeder)

For Hallaj, Iblis was a "true monotheist," so how could he worship God and still bow down before Adam in prostration?

The Quran tells us that God ordered Iblis to do so, but he refused (Quran 2:34). He then went on to blame God for misleading him and vowed to stray man from the straight path (Quran 7:16, 15:39). "The explanation Hallaj gives," said Professor Ernst, "was that God had given secret hint (ishara) to Iblis that he should not bow down and so he disobeyed, but internally he was the most loyal servant and willing to suffer punishment of being estranged from God and being punished by God in order to demonstrate his loyalty."

Though unorthodox, Hallaj makes Iblis's encounter with God sound like a tragedy.

As far as Hallaj crying out "ana'l-haqq" in public is concerned, notable Sufi masters held it was a result of his spiritual state that is incomprehensible to a layman. A Shadhili-Darqawi shaykh, Muhammad Harun Riedinger, rightly pointed to a metaphor Ghazali employs to explain the limitations of rational mind at comprehending mystical experiences:

"It is like an impotent man asking his friend how his wedding night was and getting the reply: 'Oh, I was in the 7th heaven.' How can the impotent asker 'understand' the bliss of his friend?"

Sufis generally do not consider that Hallaj was claiming to be God, but that his ego had been annihilated. "As `Attar pointed out, when the burning bush said to Moses, 'I am God,' it was not the bush speaking, but God manifesting through it. In the same way, it was God speaking through the voice of the annihilated Hallaj," said Professor Ernst.

Hallaj's spiritual intoxication yielded "theopathic locutions," where God speaks in the first person through a saint. And according to Timothy Winter, lecturer of Islamic Studies at Cambridge University, this "phenomenon is not confined only to mainstream Sufism, but where it is, it is regarded as the consequence of 'fana,' the maqam or station of Annihilation. When the personhood of the saint is stripped away by mujahada (spiritual discipline), the reality of the Divine ground of being is manifest."

Al-Ghazali does not discredit the truth content of Hallaj's state but maintains that since only God is the Truth, and it is only He, who has the right to proclaim it and thus the "I" was not Hallaj's self speaking.

Ghazali however held that Hallaj's execution was justified since he had revealed the Divine secret in public.

Hallaj was not sentenced to death for uttering "ana'l-haqq." After his arrest, he was accused of various things, but, according to Professor Ernst, he was pinned down after his prosecutors discovered a document in the handwriting of Hallaj that recommended that those who were unable to afford Hajj pilgrimage could construct a model of Kaaba at home and perform circumambulation (tawaf) and give alms to poor and feed some orphans and they would have completed the Hajj.

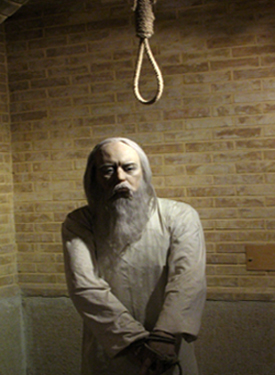

[Mansur al-Hallaj's wax statue in Shiraz. Photo credit: Carl Ernst.]

"At that point one of the judges turned to Hallaj and said in Arabic 'damuka halal,' that is, your blood may legally be shed. In other words, now we have you," said Professor Ernst, a specialist in Islamic Studies. "But then Hallaj said that I found this in the writings of Hasan al-Basri, so that was a kind of technicality, but he was given no opportunity to explain or repent."

Hallaj was prosecuted at a time when the Abbasid caliph was extremely weak and did not have the ability to make a unilateral decision. In fact, the Abbasids were so weak that they completely removed from power a little over two decades later, in 945, by the Shiite Buyid dynasty coming in from the Caspian.

This raises suspicion on why a Sunni caliph allowed the trial to go on for nine years when the Hanbalis and other conservatives revered Hallaj as a pious man, who prayed 2,000 (yes, 2,000) units of voluntary prayers at a time. "Only the Shiites were critical of him, mainly because he proposed an alternative authority," said Professor Ernst. "When asked, what is your madhab (religious sect)?, Hallaj would say: I pick the most difficult rulings from all schools of law and follow that."

The question of why certain Sufis were executed can only be understood by the politics. While speaking of Sufism, we don't naturally think of politics, we simply assume that a lover of God was martyred by a hardliner, but Mr. Ernst says there is more to it: "You have to look at the political contest and it is only when the political authorities find it useful to persecute an unusual figure that's when the incident takes place."

It seems that diverting attention from crippling internal problems, like corruption within the government, to something ridiculously trivial is an ancient tactic.

But from a Sufi perspective, it is futile to analyze the outward series of events that led to Hallaj's execution. "Martyrdom does not belong in this realm," Shaykh Riedinger notes. "If God is pleased with His bondman and wants to bestow the crown of martyrdom on him, He puts him into such an outward scenario -- political or other wise -- that will eventually lead up to the situation, where the Divine intent is realized."

- `Ayn al-Qudat Hamadani, a Persian mystic, who was executed in 1131 by the Suljuks.

- Shahab al-Din Suhrawardi, aka Shaikh al-Maqtul (the Murdered Shaykh), was executed in Aleppo in 1191 by Salah ad-Din Ayyub's son al-Malik al-Zahir.

- Mas`ud Bakk was put to death in Delhi, India, by Firuz Shah Tughluq in the 1390s.

- Imadaddin Nasimi, a Azerbaijani sufi-poet, was skinned alive in 1417.

- Shah Inayat was executed by Yar Muhammad Kalhoro in 1718. This was part of a popular uprising similar to a peasant revolt, so it could equally be considered political.

- Sarmad Kashani was beheaded on Emperor Aurangzeb's orders in 1661 for writing a poetry that was considered heretical.