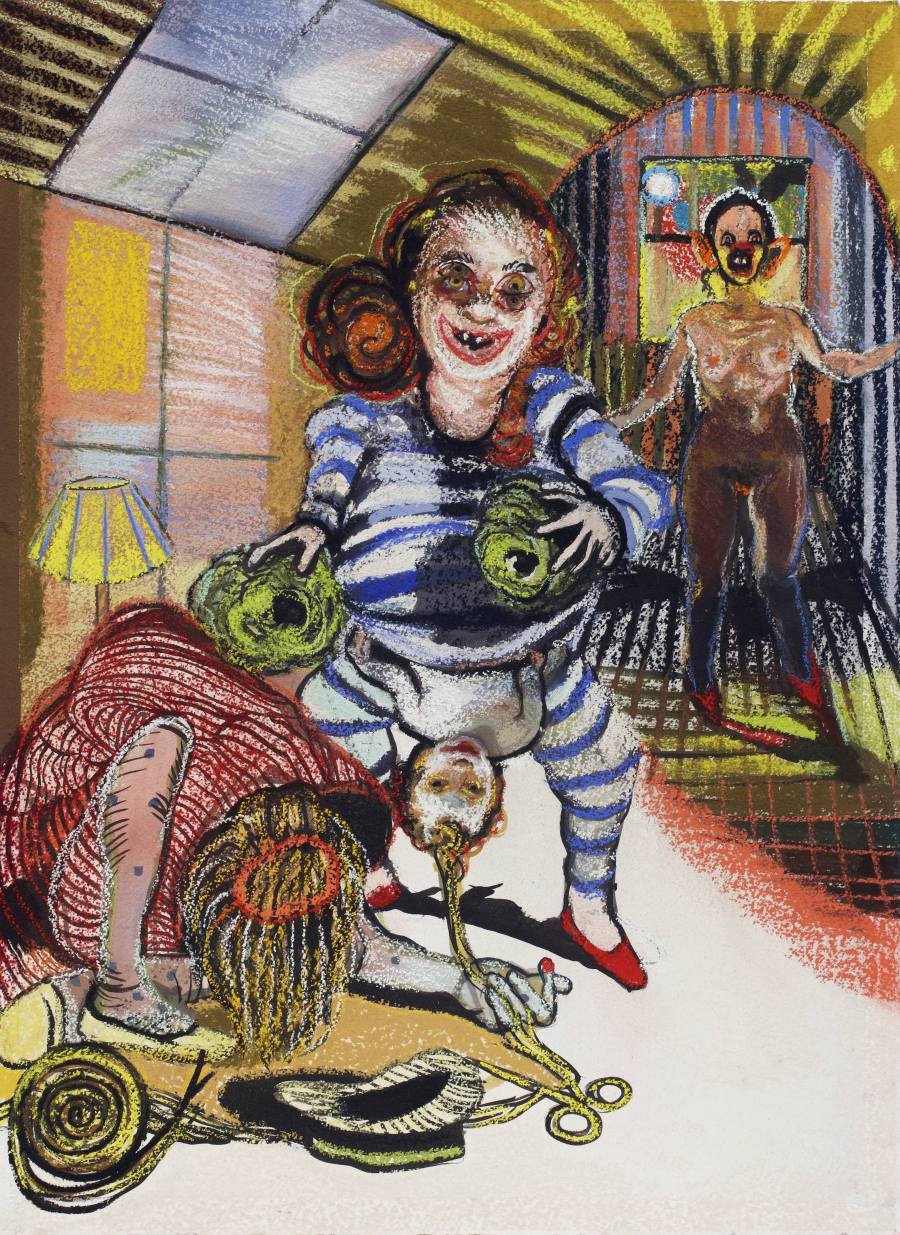

All Fur III, 2011-14 Gouache and chalk pastel on Arches paper, 22 x 30 inches (55.9 x 76.2 cm). Courtesy of the artist.

The tale of "All Fur" begins when a dying queen tells her king he must only marry a woman as beautiful as her. He obliges, only to unfortunately discover the sole candidate for the position is his devastatingly lovely daughter, who grows up to look just like her mother.

Horrified upon hearing the news, the daughter runs away, covers herself in furs and soot until she resembles a woolly creature, earning the nickname All Fur. She's soon captured and forced to cook in a neighboring king's kitchen, where he eventually removes her fur disguise, recognizes her captivating beauty, and makes her his wife.

"Thereupon the wedding was celebrated, and they lived happily together until their death."

And that's how it ends. Sort of happy, mostly creepy. A bizarrely sunny ending to a grisly sequence of incestuous events. A short myth as finely crafted and irresistible as a scrumptious pastry, and as grotesque as if said pastry, with a prick of the fork, oozed blood.

This is one of Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm's famed Grimm fairy tales -- the un-sanitized versions -- written between 1812 and 1857 in Germany. The Grimms' original stories, infested with gross and marvelous detail, remain widely unknown to this day, having been replaced by the more "kid-friendly" alternatives. British translator and writer Edgar Taylor initiated the switch when he translated the stories from German to English in 1823, omitting the more gruesome details along the way. It was this Disney-ified adaptation that dictated the popular understandings of stories like the tale of Cinderella today. (In the original, the stepsisters cut off their own toes and are blinded by birds.)

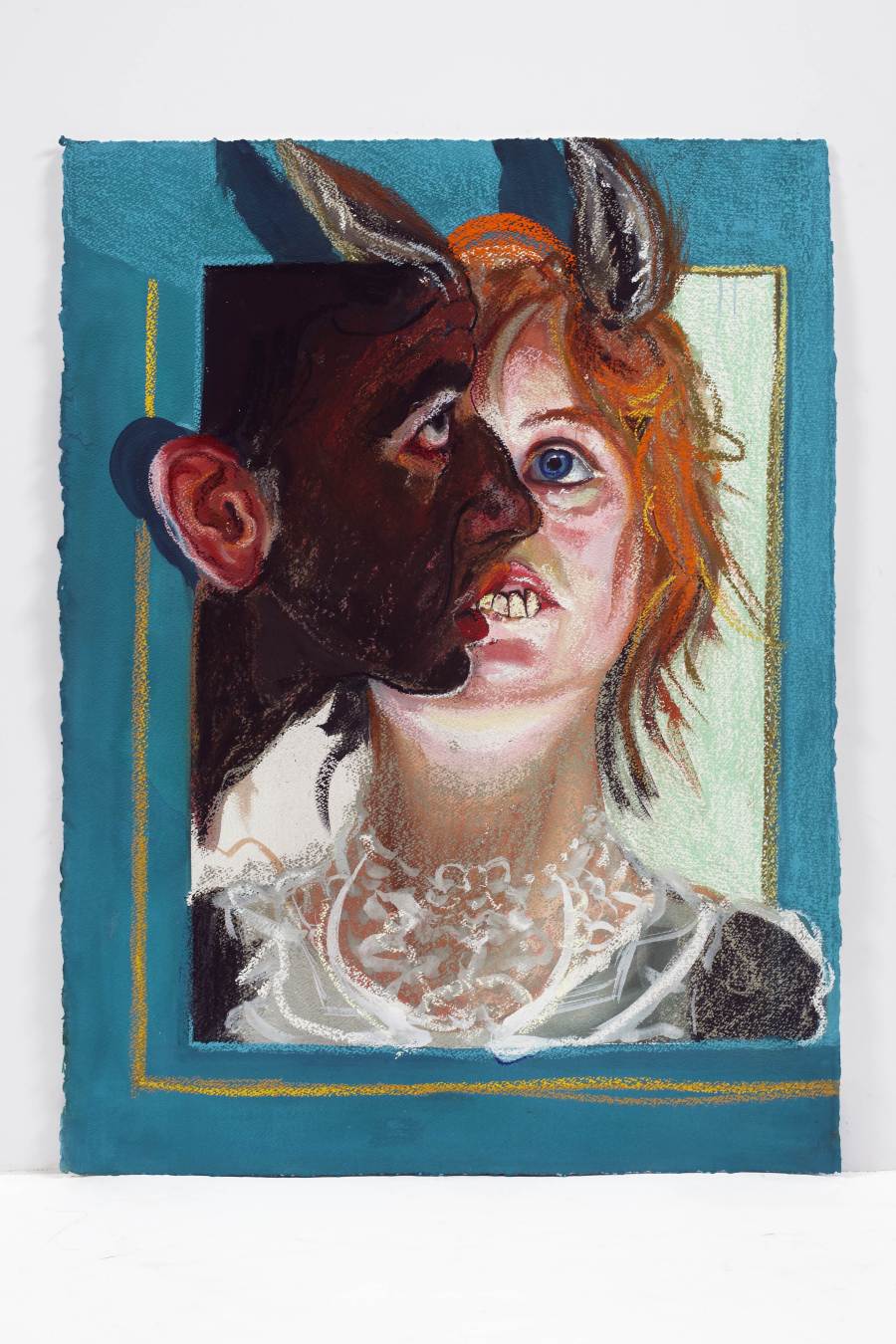

Rapunzel I, 2011-14 Gouache and chalk pastel on Arches paper,22 x 30 inches (55.9 x 76.2 cm) Courtesy of the Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, Purchase through the generosity of the Houston Endowment, Inc. in honor of Melissa Jones

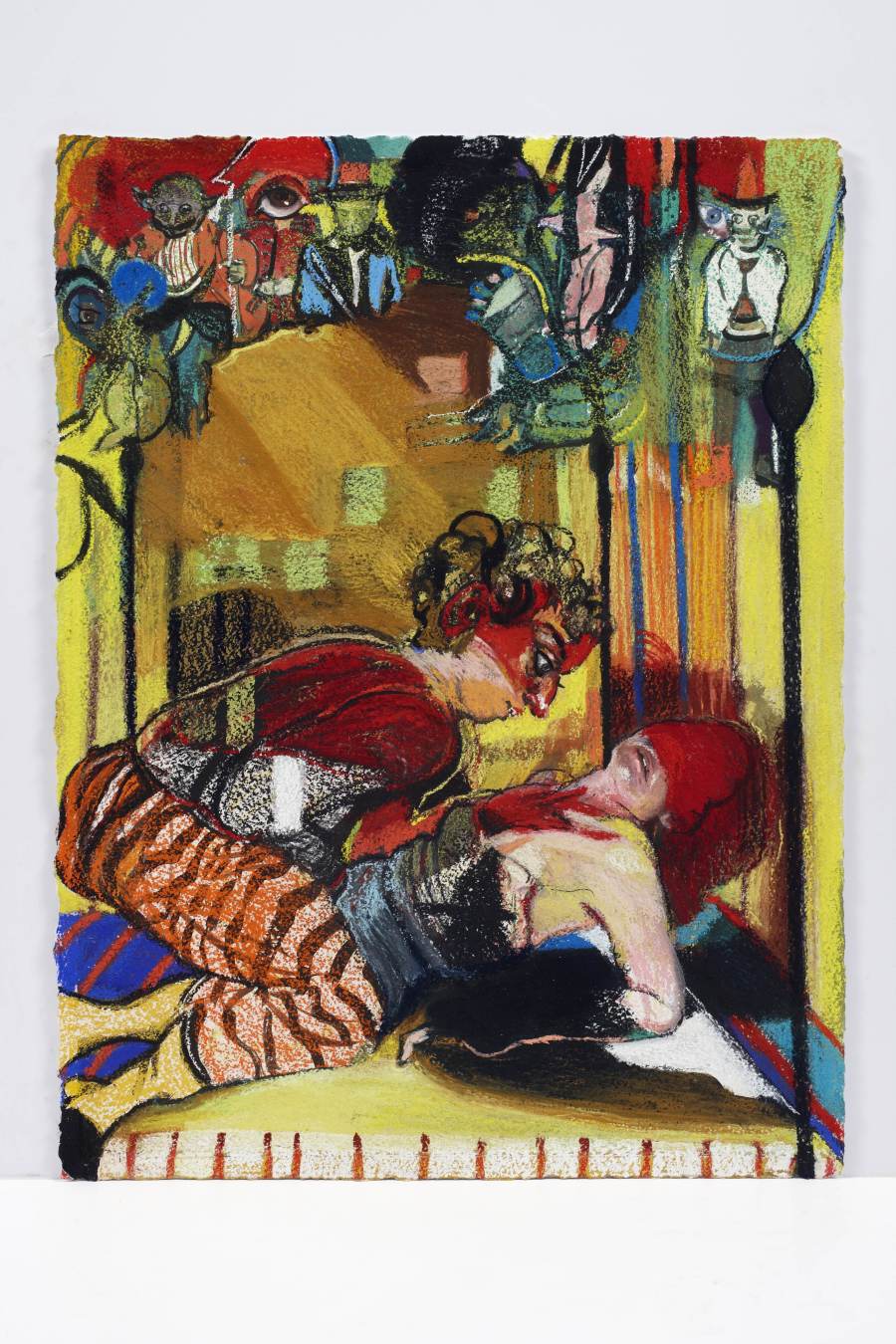

The 19th century stories are twisted, raw, decadent, bubbling and monstrous. If you've ever seen the work of New York-based artist Natalie Frank, similar descriptors flock to mind. Frank is a figurative artist, though what she does with human bodies is less representational and more transformational. It appears she can't resist splaying flesh open and seeing what transpires, humoring the possibility of person as meat, person as beast, person as sex toy, person as monster.

Often compared to artists including Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud, Cecily Brown and Jenny Saville, Frank crafts disorienting visions that resist meaning and morality, revealing that the grey zone between good and evil, beauty and horror, is actually quite colorful. Her paintings transform our safe spaces into danger zones, luring the viewer to that precarious feeling of waking up mid-nightmare to a bedroom that seems slightly, yet imperceptibly, warped.

In 2011, Frank encountered the original Grimm tales for the first time and was captivated by their feminist perspective, both in the diverse range of characters themselves and the way the stories, she claimed, were circulated by women, for women. This initial intrigue led to a massive artistic undertaking, eventually yielding 75 gouache and chalk pastel Grimm-inspired illustrations, a stunning book and a solo exhibition, all of which are coming to fruition this spring.

Frank's visual interpretations of the 19th century lore contain all the unabashed hunger and gritty detail of their source material, depicting remarkable moments from a selection of stories in forms more deliciously horrifying than most imaginations could conjure. Creatures slip effortlessly back and forth between man and beast, or happily reside somewhere in between, anchored by bugged-out eyeballs and lusting mouths. Tapping into the whimsical symbolism of artists like Marc Chagall and Odilon Redon, Frank renders fantastical happenings with such sordid precision you'd swear you had encountered such sights in real life. Then again, it's the occasional normal-seeming man, stripped nude, mouth wide open and strangely cocked, that will haunt you long after the book is shut.

Frank, like the brothers Grimm before her, has a knack for turning what's most mundane into what's most alien. After all, is there anywhere we spend more time than in our own bodies? And yet, if we could only see beneath the skin, what gnarly, unknown apparatuses would greet our eyes? Even our minds, where we carry out our daily thoughts, questionings and cravings, may hold certain urges and hazards we would be shocked, and repulsed, to discover.

Lettuce Donkey III, 2011-14 Gouache and chalk pastel on Arches paper. 22 x 30 inches (55.9 x 76.2 cm). Courtesy of the artist and Rhona Hoffman Gallery (Chicago); ACME (Los Angeles)

We reached out to Frank to learn more about her upcoming book and exhibition.

When were you first introduced to the Brothers Grimm fairy tales? Were they a part of your growing up at all?

I did not read them growing up. Paula Rego, a Portuguese artist in London, introduced them to me. I had read some of the sanitized versions but never the un-sanitized. I was surprised at how much I didn't know about the original stories, and started to read up on their 19th century origins. I was amazed, especially with their feminist roots.

Can you expand on that?

They are folktales that are pulled and collected by women. The Brothers Grimm were philologists and were interested in recording the language of the tales. The women actually came to the brothers' home and told them the stories that they then recorded. But it was the first time in literature that women had a voice in this way. These 19th century Grimm versions were the first time women were able to shape their own representations, evil and divine.

You mention in your introduction to the tales that they served as an outlet for women, allowing them a space outside of the ordained silence, obedience and Christian values of the time. Would you say fairy tales were an underground or radical form of literature?

They were. They were considered a woman's art, not high art. They were stories that women told each other in the well or in the nursery or in the home. To have them published in such a widespread and public way was pretty radical.

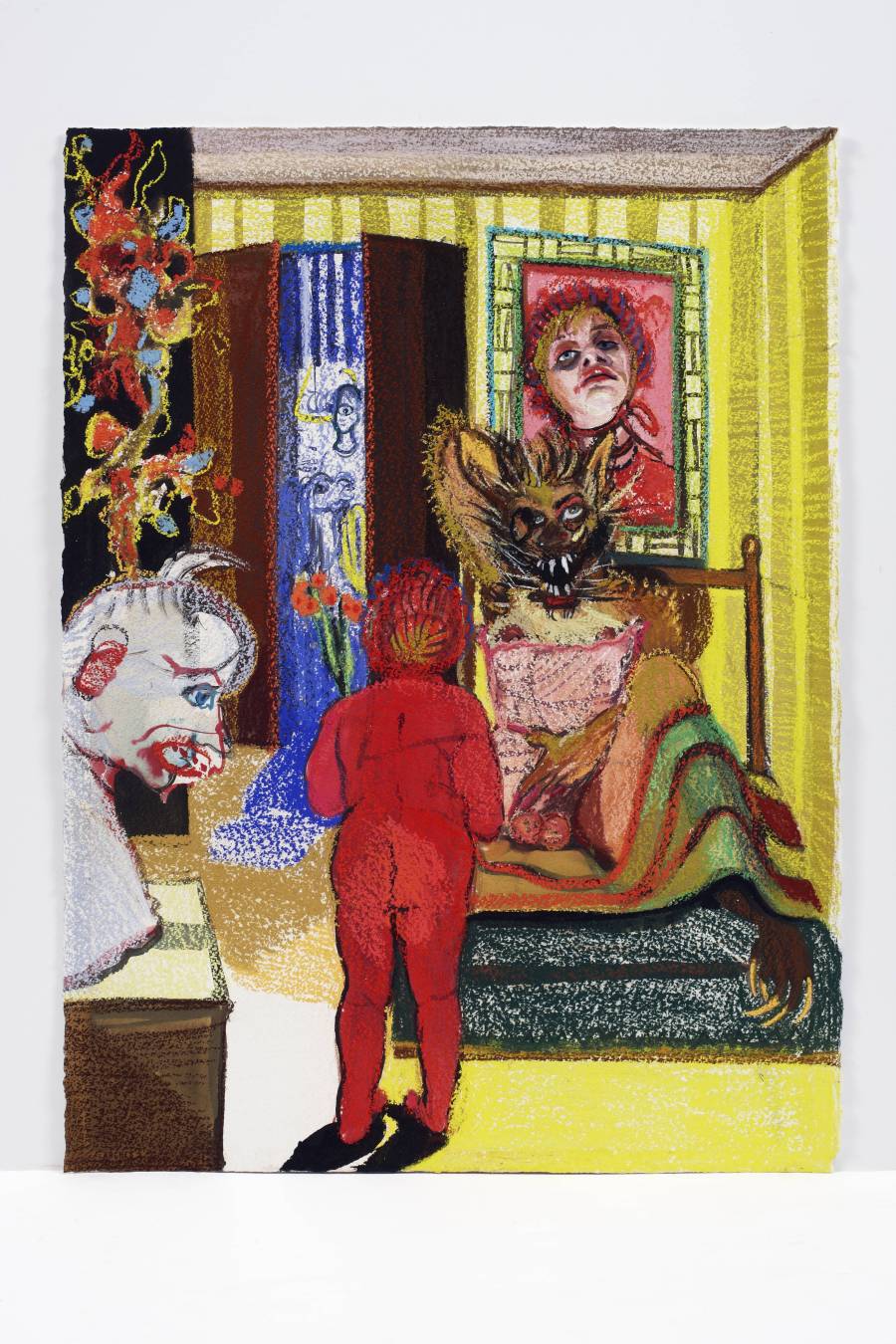

Brier Rose III, 2011-14 Gouache and chalk pastel on Arches paper, 22 x 30 inches (55.9 x 76.2 cm). Courtesy of the artist and Rhona Hoffman Gallery (Chicago); ACME (Los Angeles).

And you felt the works themselves were feminist as well?

They definitely struck me as feminist because of the range of roles that women play in the stories. From witches to helpers to evil stepmothers to children -- the pure breadth of roles was something that struck me as very feminist. And the way that women were treated both as aggressors and lesser characters.

Marina Warner wrote a lot on the feminist symbols in fairy tales and their origins. For example, women's helpers are depicted as birds, because of these gynecological instruments that doctors used that resembled beaks. So many symbols were representative of life at the time -- like the high rate of mortality, especially during childbirth, led to the character of the evil stepmother. The worlds are shaped from the perspective of women.

The shape of the stories seems to differ from the traditional format of buildup, climax, resolution. Would you say the shape of the narrative of these fairy tales is feminine in a way?

I think some of the stories have the traditional happy endings. But in the un-sanitized versions they're certainly not clean, dignified, happy stories where women are diligent and then are rewarded. It's much more complex than that.

There are two stories with incest, "All Fur" and "The Maiden Without Hands," and in "The Maiden Without Hands" the father wants to give the maiden to the devil, but the daughter cries on her hands and she is clean so the devil cannot take her. So the father chops off her hands and the maiden cries on her stomach so the devil still can't take her. And then she wanders and ends up in a prince's garden and she eats this magical fruit and eventually she marries the prince and he makes her these silver hands. They end up happily ever after, but it's not your typical story where the prince picks her up from her lower class life and she becomes a princess. It's much more complicated and violent.

Even the fact that the stories are so vulgar and violent is feminist in a way.

Yeah. There is a story that's not very well known called "The Stubborn Child." It's just a short paragraph about a mother who has a naughty child and buries him in the ground. And his arm keeps popping out and she keeps hitting it with a stick. So that's not a traditional fairy tale.

What was your initial idea for the project?

Initially it was just for fun. I just started going through Jack Zipes' collected tales which contain 211 stories. I started to get serious about drawing them like two years ago. I thought it would make quite a good book -- just the way the stories fit together, and the fact that they are oral tales, so they are often iterations of each other. And they relate so beautifully. Collectively they make such an interesting picture of 19th century life from the vantage point of women.

I wanted to combine beloved fairy tales -- where people didn't really know the un-sanitized versions and would probably be shocked to read them. And then some of the completely unknown stories, like "All Fur."

Cinderella II, 2011-14 Gouache and chalk pastel on Arches paper 22 x 30 inches (55.9 x 76.2 cm) Courtesy of the Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin. Promised gift of Kathleen Irvin Loughlin and Christopher Loughlin

Can you talk a little about the relationship between text and image in the works? They're clearly interacting and dependent on one another in a way, but it doesn't seem like illustration is the right word.

They're not, and it was important for me not to make illustrations or didactic drawings. I really just read the stories and thought about key scenes that, in my mind, were necessary to represent the narrative. There are anywhere from one to five drawings per story and 36 stories. I thought a lot about using tropes from illustrated books and manuscripts, I looked at a lot of old fairy tale editions, other illustrations of the Grimm.

There have been very few fine artists who have illustrated the Grimm -- David Hockney, Kiki Smith and Tomi Ungerer are some. But no one has really illustrated them enough. I wanted to push each one in a different direction. I was thinking a lot about how to represent time in a drawing. It was definitely a challenge to do a project over a four or five year time period and make it feel consistent yet varied.

In your paintings you incorporate the faces of people from your family and home life in your work. Did you do the same with your drawings?

Yes. I put my grandfather as Blue Beard, decapitated on the bed. My father is peeping into a window with a tail. He's also Rumpelstiltskin. Our neighbor in Canada appears as Rapunzel. Anyone was fair game.

The domestic space is often thought of as a safe space but in the fairy tales and in your other paintings it becomes a site of horror. Is that part of what drew you to the fairy tales?

I think in my paintings the domestic setting is the site of horror because it's where people are kept together, almost like animals, and bad things happen because of proximity. With the Grimm tales, when you've had so many mothers die and you get evil stepmothers stuck in the house with their children, it was the site of horror. It was the site of protection because venturing out into the world where you might meet a wolf was also a scary place. But I think being around other people in the home was also terrifying.

Yes, it's crazy that all the incest and murder and cannibalization was happening in real life. It all feels so horrific and fantastical now.

Yes, all of it. I think what I'm weary of for this show is that people dwell on the gruesome side. I don't see these stories as gruesome, I don't see the drawings as gruesome. For me, it's the undercurrent of life. And, because of how elegant and poetic and comical the Grimm fairy tales are, I found them to be joyful and very funny. But still, of course, exploring the violence and sexuality of everyday life.

I wanted to ask you about the relationship between humor and horror. Do those categories often overlap for you?

They do. Sex, I would say, straddles -- no pun intended -- both of those categories. For me, it certainly does. I think, like most figurative painters, I have a really complicated relationship to the body. I find it both repulsive and entrancing. The idea of people turning into animals seems really appropriate, because people often behave like animals. And animals like people.

So maybe that's why the Grimm resonated with me so much. All of the transformations and attention to detail. The way that women really see others and their heightened sense of perception really comes across in the Grimm.

Little Red Cap I, 2011-14. Gouache and chalk pastel on Arches paper, 22 x 30 inches (55.9 x 76.2 cm). Courtesy of the artist and Rhona Hoffman Gallery (Chicago); ACME (Los Angeles)

Will the text be on view along with the images at the Drawing Center exhibition?

We're going to have the book available at the Drawing Center to take through the show and I think we'll have some of the stories laminated that you can take around. But none of them will be on the wall. I think it's important that the drawings stand for themselves. They will be grouped by story, but you don't necessarily need the story.

Was there anything that surprised you about this entire experience?

The process of putting together the book was so special and new to me. That, for me, was the biggest component of this whole body of work. Taking the drawings that represented things and thinking about their order and how they would read, and thinking about the title pages and the borders and just, all in all creating a whole other world for the drawings to live in. Why the Grimm tales feel so powerful when you read them is that they really evoke this world. Putting all of it together made me think about drawing in a different way.

What do you think is dangerous about sanitizing or commodifying fairy tales, if anything?

I think it's terrible. It belittles children. It lies to children, really. Children should learn the way the world works and children are intelligent individuals. I think when adults patronize children it's to no one's favor, because sooner or later they're going to end up in the world and they're not going to know what to do.

I feel like visual art is the art form that's least accessible to children -- as opposed to film and books and theater. Do you think there should be more opportunities for children to experience art?

Absolutely. Growing up in Texas, in school, it wasn't allowed to look at images of naked bodies, which I never understood. It was the same criticism the brothers Grimm had before their sanitized version. I absolutely want children to look at these. Children should not be censored, art shouldn't be censored.

"Natalie Frank: The Brothers Grimm" runs from April 10 until June 28, 2015 at the Drawing Center in New York. The accompanying book, published by Damiani and distributed by D.A.P., will be available soon.