She's risqué but never explicit. She's flirtatious but fiercely independent. She's erotic but always safe for work, a welcome sight for your teenage cousin and prudish mother alike. She's the pin-up girl, an all natural American sweetheart created to win the adoration of men across the country.

By Alberto Vargas (c) the Max Vargas Collection

You'd know her if you saw her -- the rosy cheeks, bouncy curls, hourglass figure and penchant for thematic lingerie are pretty much a dead giveaway -- but how exactly did she come to be? Join us as we travel back in time and explore the origins of the pin-up girl, with the help of the newly released "The Art of the Pin-up." It's a peculiar journey, one that overlaps with both women's liberation and women's objectification along the way. Our timeline begins, oddly enough, with the invention of the "safety bicycle" in the 1800s.

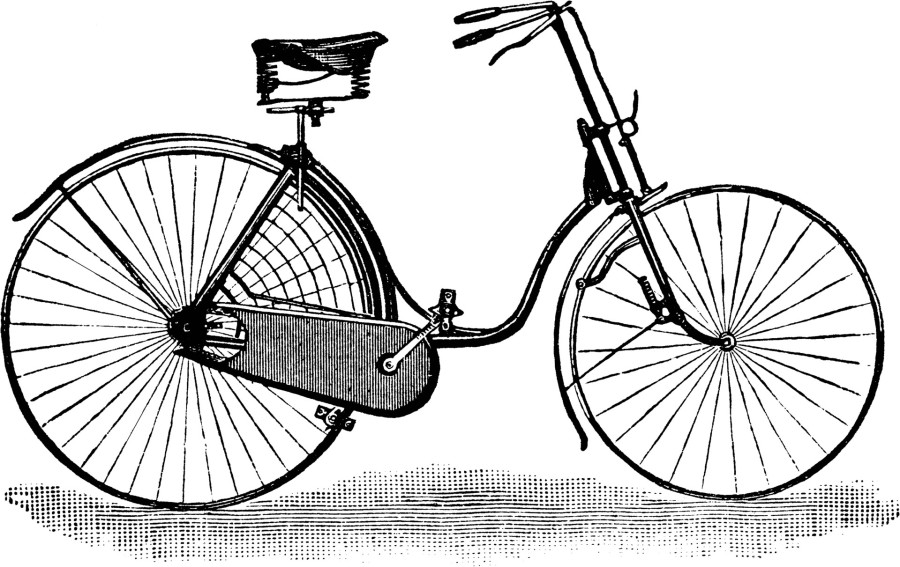

Early 1800s: Enter The Bicycle

A Lady's Safety Bicycle from 1889, via Wikipedia Commons

Here's a bit of context before we dive into the history. "Safety bicycles," as they were known, caused quite the raucous amongst Western women in the early 19th century when they were introduced. Doctors and ministers denounced the new fangled vehicles, claiming that bouncing harmed women's fragile insides and the friction of the seat was likely to get them aroused. To suffragists, however, the bicycle was the "freedom machine," freeing women of ties to a male escort.

Early 1800s: Women Wear The Pants

1897 advertisement, via Wikipedia Commons

Soon after bicycles hit the scene, women eschewed their petticoats and layered skirts in favor of bloomers and boots. This small fashion shift revealed women's legs, and women's bodies, in mainstream culture like never before. Women were simultaneously more masculine and also more sexual. Things were getting interesting.

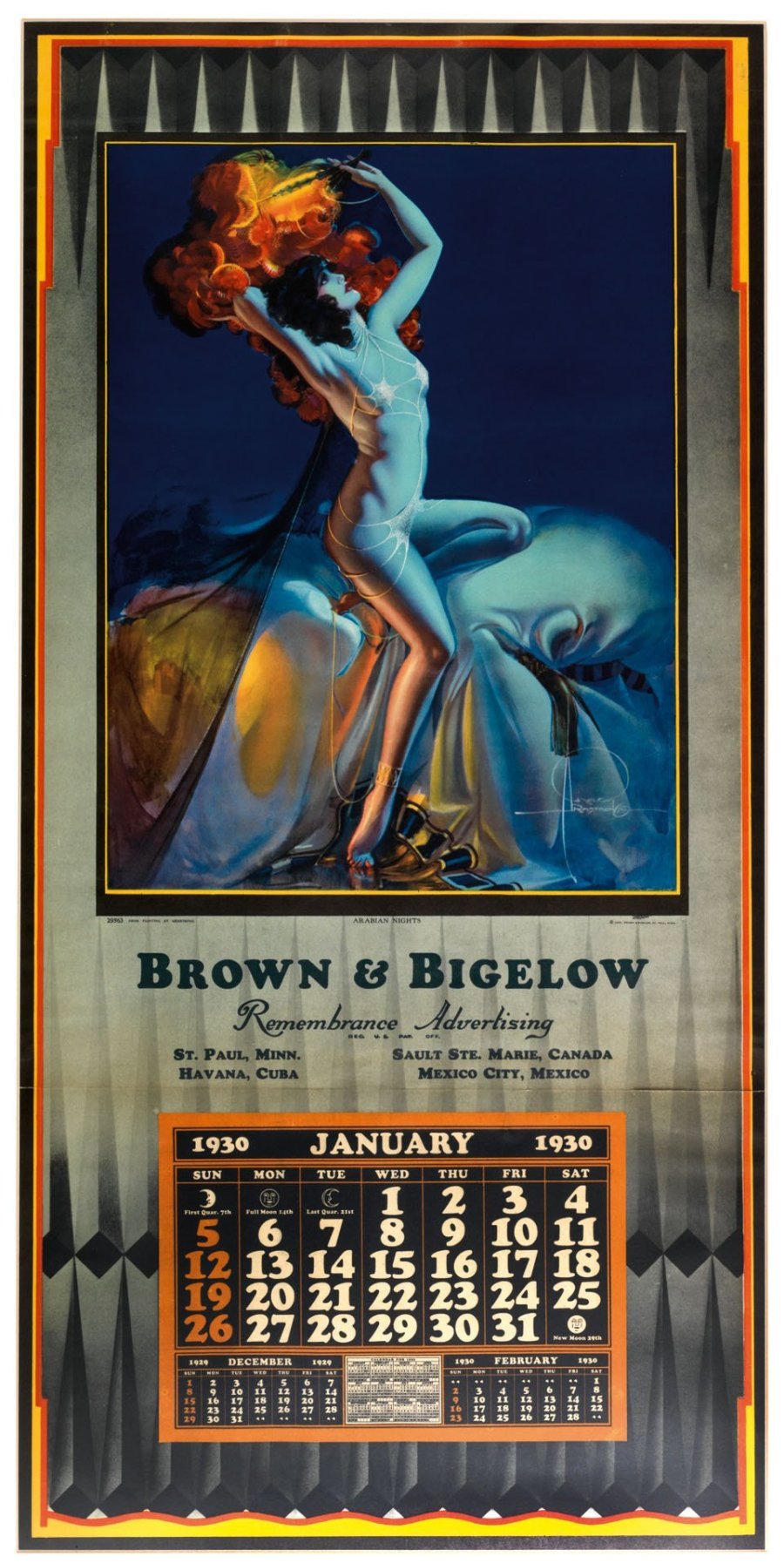

1889: The First Calendar (Girls)

By Rolf Armstrong (c) Brown & Bigelow, via Taschen Books

Thomas Murphy and Edmond Osborne print the first calendar featuring ads beneath the images. The concept was inspired; calendars do guarantee an entire year of ad space. The first calendar, featuring an image of George Washington, and it unsurprisingly didn't do so hot. In fact, the calendar market didn't heat up until 1903 and the release of the first girl calendar, titled "Cosette."

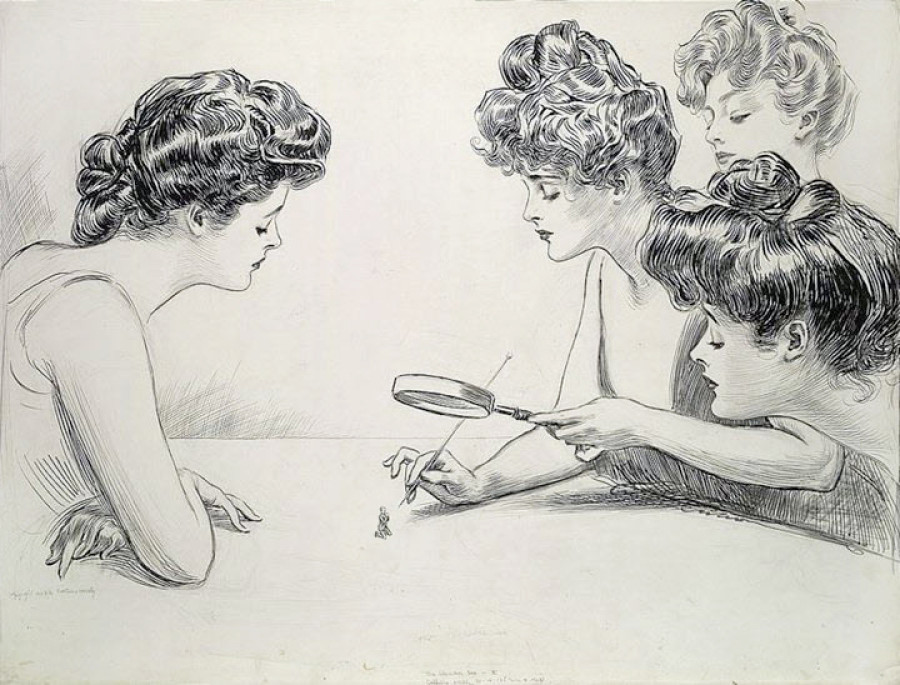

1895: The Gibson Girl

Original pen and ink drawing for "The Weaker Sex," illustration by Charles Dana Gibson, via Wikipedia Commons

Charles Dana Gibson, an illustrator for Life magazine, shook up women's fashion with his cover illustrations of bosomy women with hourglass torsos, dark piles of hair and full, luscious lips. Inspired in part by Gibson's wife and her family, this national icon became known as the Gibson Girl, a girl America loved, known for her simultaneous sensuality and independence. She was, in a sense, the first "dream girl," unattainable aside from pinning her photo up on your wall.

1895-1932: The Gibson Copycats

Harrison Fisher illustration, via Wikipedia Commons

After the success of the Gibson Girl, many other magazines followed Life's lead. Howard Chandler Christy crafted the Christy Girl for The Century magazine in 1895, and Harrison Fisher's Fisher Girl covered Puck Magazine and Cosmopolitan from 1912 until 1932. All the women were similarly beautiful and aloof.

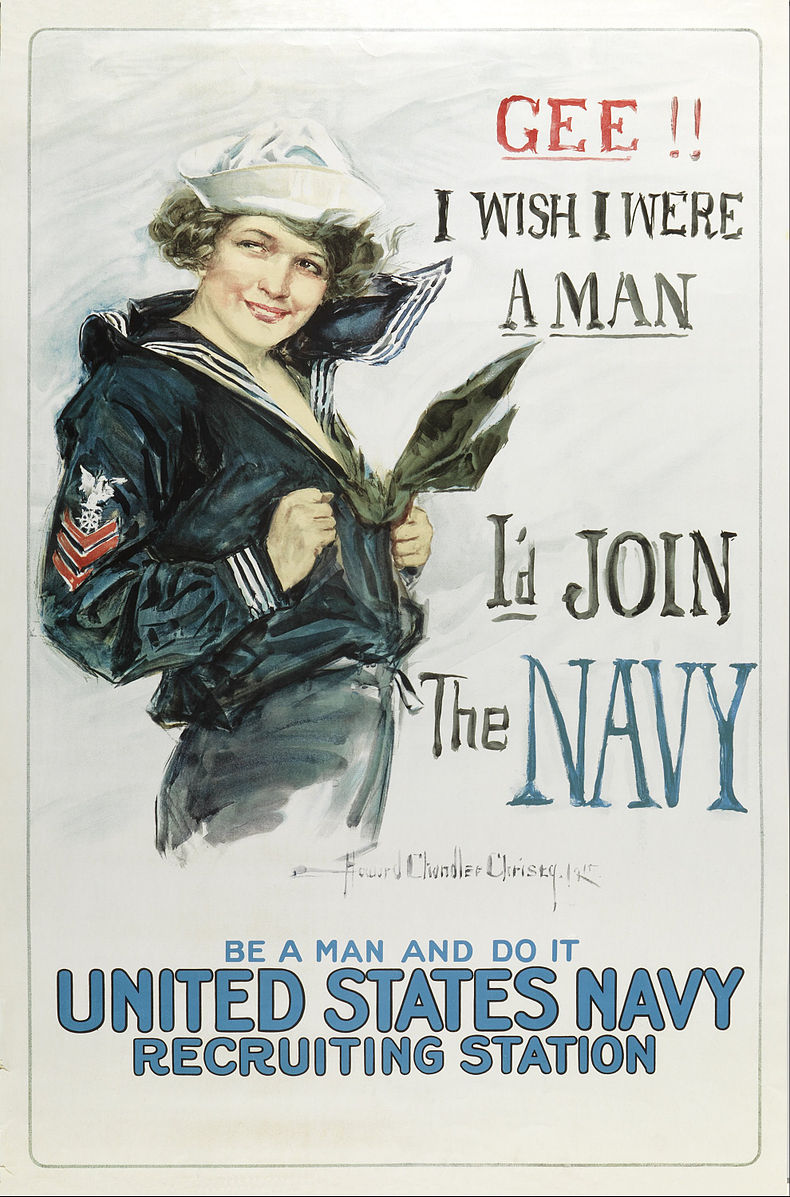

1917: Pin-Up Propaganda

By Howard Chandler Christy, via Wikipedia Commons

During World War I, American President Woodrow Wilson formed the Division of Pictorial Publicity to stir up patriotism and inspire new troops to fight. One of the main tropes of said posters included pretty women, often dressed in sexy military ensembles and announcing messages like "Gee, I Wish I Was A Man Man. I’d Join the Navy," and "Be a Man and Do It." Not the most subtle.

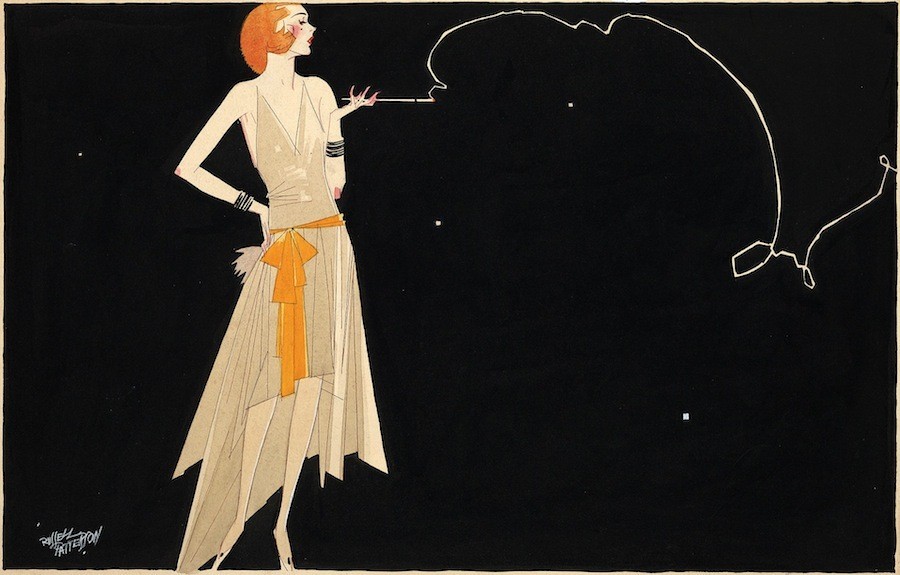

1920s: Those Roaring '20s

Where there's smoke there's fire by Russell Patterson, via Wikipedia Commons

With their partners away at war, women in the 1920s had tasted freedom and weren't willing to let it go. The jazz age brought with it shortened hems, spiked illegal alcohol, bobbed hair and a heightened sense of youthful rebellion. The free-spirited flapper generation was wild, free and eager to show some skin. Artists like Rolf Armstrong responded to the trend, dressing his pin-up girls all the more scantily as well.

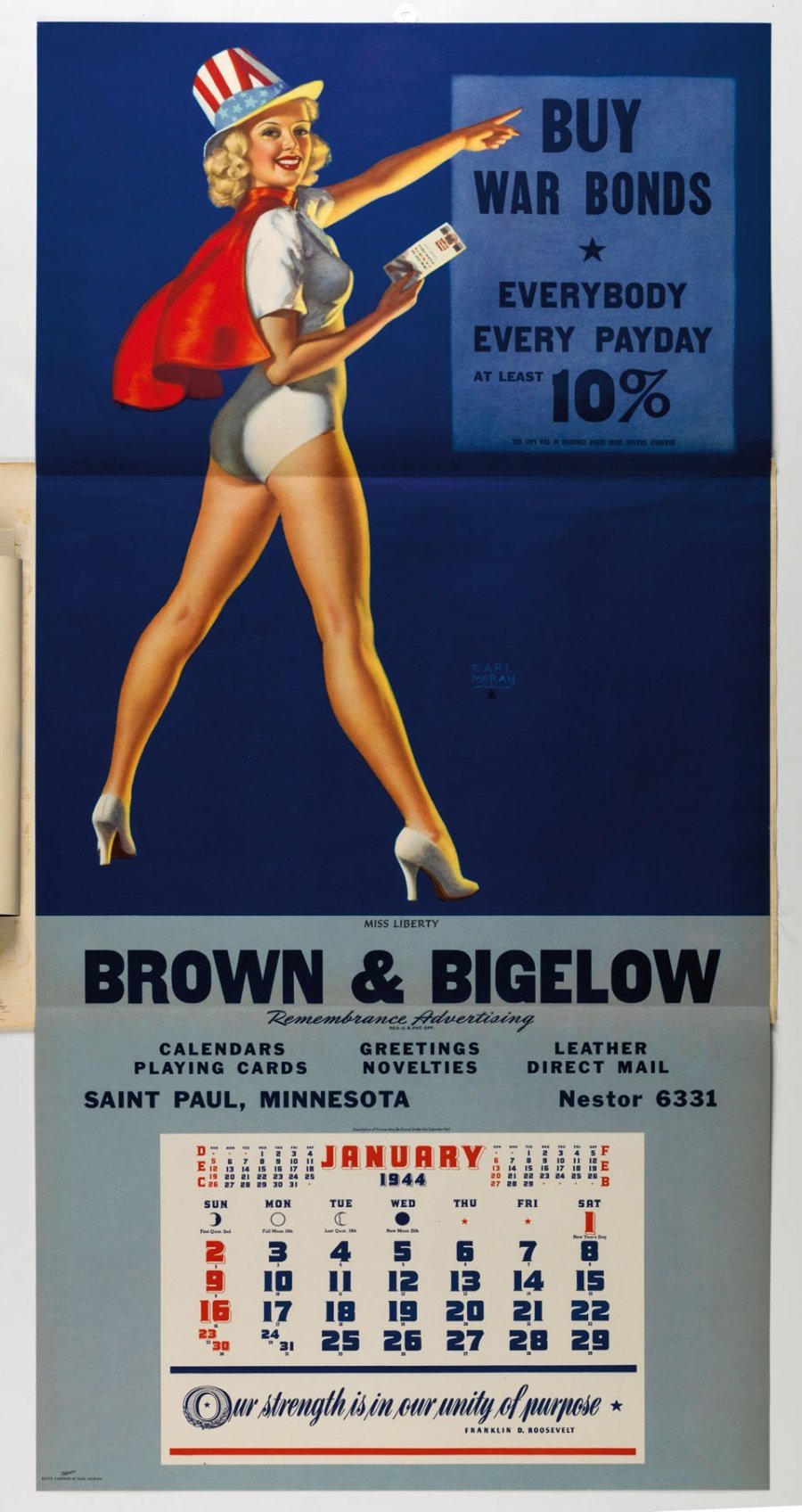

1940s: Psychologically Perfected Propaganda

By Earl Moran (c) Brown & Bigelow, via Taschen Books

World War II captured the pinnacle of pin-ups, as carefully designed by the U.S. government to boost morale by presenting an all-American view of the sweetheart waiting for him -- the girls worth fighting for. These pin-up photos were found pasted inside barracks, hung in submarines, and tucked into soldiers' pockets.

1950s: People Realize Sex Sells

By Peter Driben, via Taschen Books

Soon the erotic tactics employed for war advertising were extended to all advertising, as first actualized by Madison Avenue in the 1950s and 1960s.

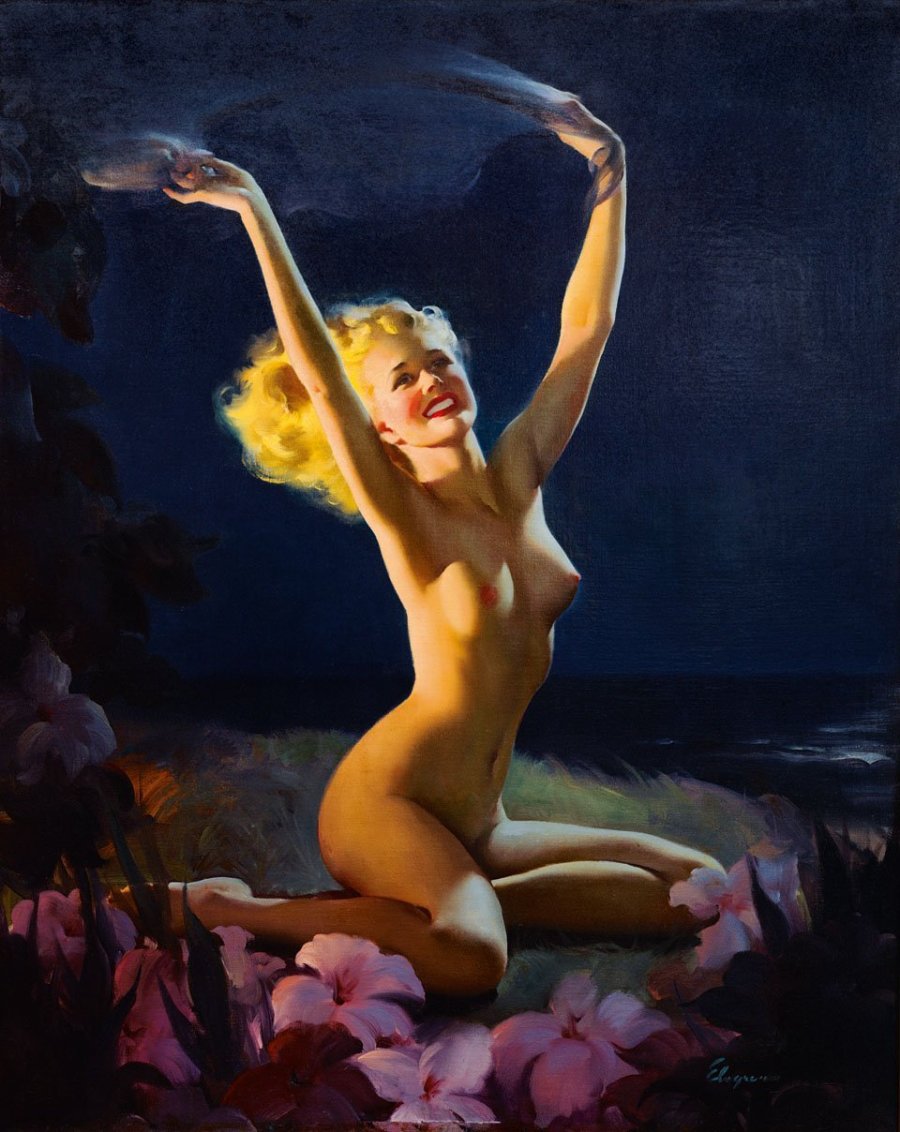

1953: Playboy Is Born

By Gil Elvgren (c) Brown & Bigelow, via Taschen Books

Hugh Hefner launched his notorious nudie mag, using pin-up magazines as his muse, yet aware that the future of the female image lied in photography. By 1955, most magazines looked more like Playboy than the pin-up covers so popular ten years before. Once the magazine had surpassed the pin-up in popularity, there wasn't as pressing a need to preserve the women's innocence. The images weren't above the bed, but in the garage.

1978: The Collecting Begins

Zoe Mozert. Mitchell Mehdy Collection, via Taschen Books

Right when pop culture at large was losing interest in pin-ups, Charles Martignette was finally growing old enough to purchase them. Martignette, who'd begun lusting after pin-ups at only eight years old, acquired his first at 27, and spent the 1980s buying up all he could. The obsessive fellow amassed a 4,300-piece collection of pin-up artworks. They were stored in warehouses and never exhibited.

1980s and 1990s: Pin-Ups Get Artsy

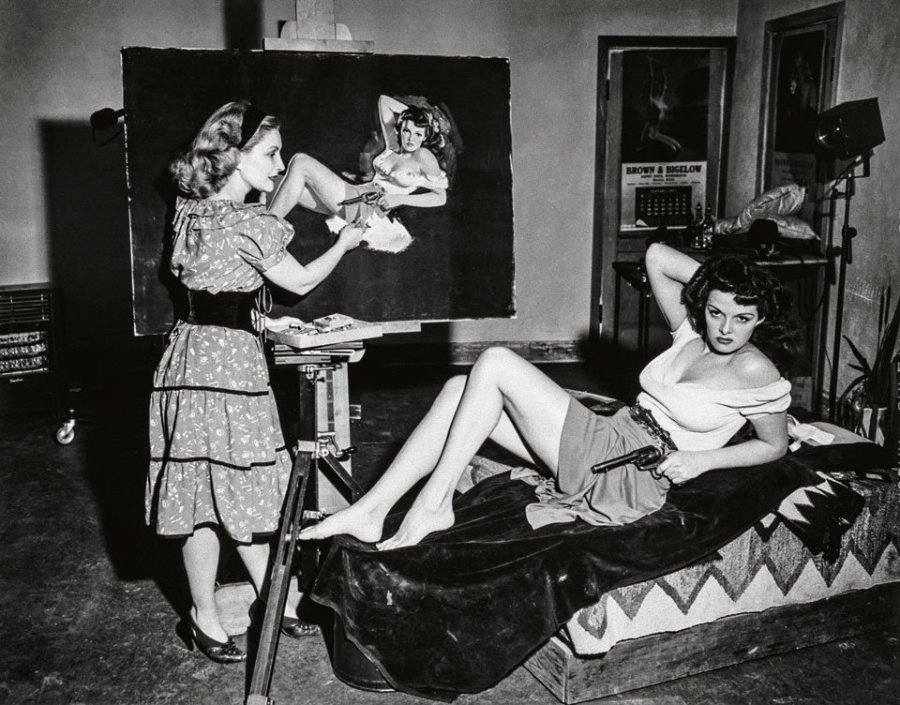

Zoe Mozert painting Jane Russell for The Outlaw film poster, via Taschen Books

Pin-ups emerged from their neglected state thanks to an exhibition organized by Louis Meisel in 1982 and the publication of "The Great American Pin-up" in 1996.

2008: The Collection Disperses

By Enoch Bolles, via Taschen Books

Martignette died unexpectedly of a heart attack in 2008, at which time his extensive 4,300-piece collection was passed on to the Heritage Auctions in Dallas, Texas. It took 12 auctions over four years to disband the massive compendium, the largest collection of surviving original pin-up art. Pin-up artworks were removed from the warehouse and free to exist as they were always intended to -- where they could be pinned up.

Information and images for this timeline came courtesy of Taschen's "The Art of Pin-up." Check out our earlier coverage of the book here.