This month marks the 25th anniversary of "Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Moment," a photography exhibition that attracted widespread public outrage for its graphic imagery, so much so that the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. canceled the show before it even began. To pay tribute to the occasion, Sean Kelly gallery in New York presents "Saints and Sinners," a collection of Mapplethorpe's images that similarly evoke art and morality's many shades of gray.

The 1989 exhibition sparked a dialogue on sexually explicit images and the true state of freedom of expression, showcasing, for one, a dramatically lit photograph of a man urinating into another man's mouth. Not surprisingly, the work sparked backlash from conservative politicians wary of funding for the arts, and "The Perfect Moment" soon incited a culture war that swept the nation, exposing the simple power of a monochromatic portrait. The traveling photographs eventually made their way to other locales, becoming a turning point for artistic liberation while leaving Mapplethorpe's transgressive imagery engrained in the nation's cultural memory for years to come.

Bruce Mailman, 1981 © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. Used by permission. Courtesy: Sean Kelly, New York

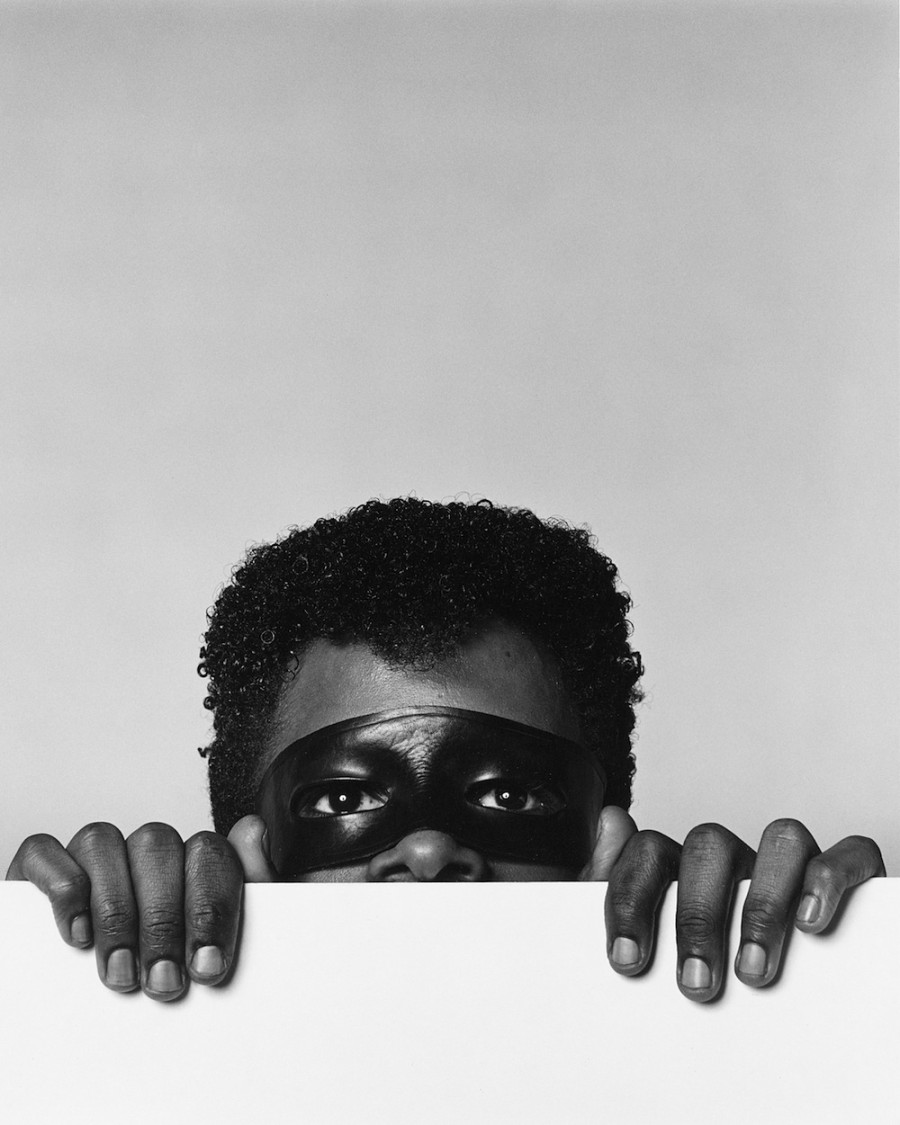

Christopher Holly, 1980 © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. Used by permission. Courtesy: Sean Kelly, New York

In honor of Mapplethorpe's deviant imagery and fearless eye, Sean Kelly Gallery is exhibiting 54 photographs that reveal the complex dualities and ambiguities in Mapplethorpe's work. The show is divided into 27 pairs of images, partnered for their aesthetic parallels or ideological oppositions. "Bruce Mailman" (1981) and "Christopher Holly" (1980), for example, both peek out from behind a surface, exposing a portion of their face. One wears a hood, the other a mask; one against a white background, the other black. Though little information is disclosed about the subjects, the viewer feels compelled to label one as hero, one as villain, though it's difficult to decipher which is which.

Some of Mapplethorpe's pairings are obvious in their message, but most aren't so black and white. In the end, the images reveal the multiplicity of interpretations lurking in a single image, no matter how straight-forward it may seem. The exhibition's title, "Saints and Sinners," toys with the idea of an unshakeable morality, aligning his formal application of lights and darks to the lightness and darkness of the human spirit.

"His photography is not so much shameless as beyond shame," The New York Times' Michael Benson wrote 25 years ago of Mapplethorpe's work. "Formally and psychologically, he was fascinated by the relationship between light and dark, black and white. Like Andy Warhol, whom he admired, he was raised a Roman Catholic and he continued to depend upon Catholic iconography and ritual: in this self-portrait, he presents himself as bishop or priest."

See more of Mapplethorpe's pairings below and let us know your interpretation in the comments.

Colin Streeter, 1978 © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. Used by permission. Courtesy: Sean Kelly, New York

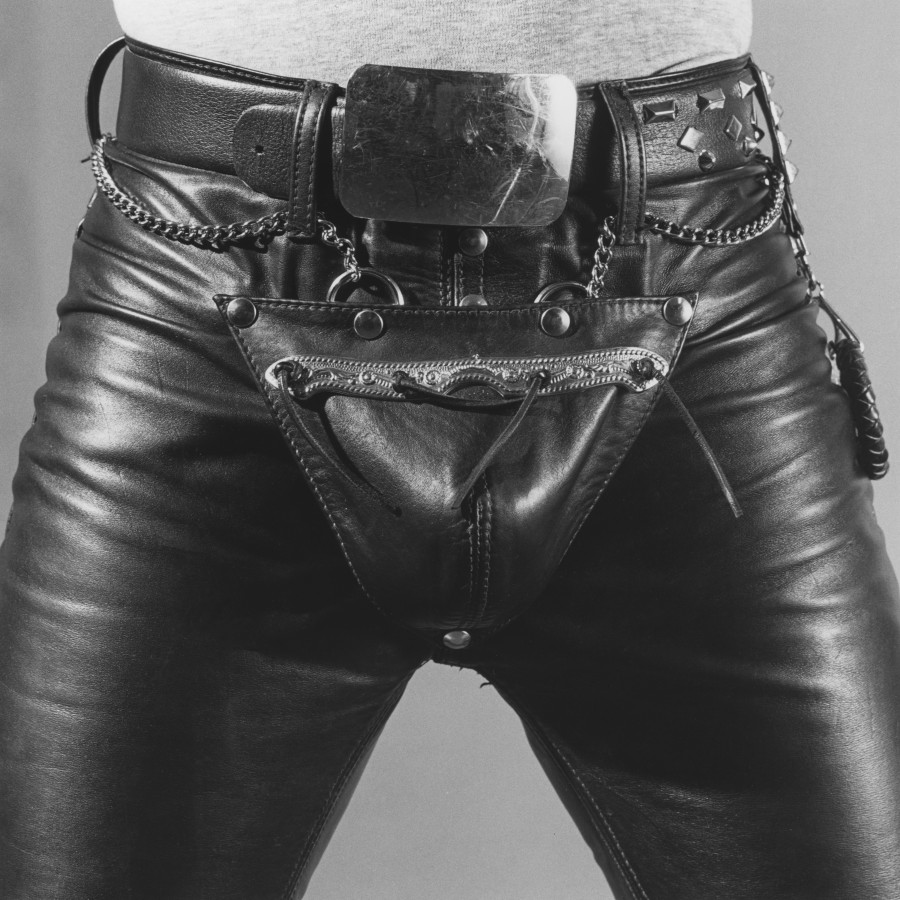

Leather Crotch, 1980 © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. Used by permission. Courtesy: Sean Kelly, New York

Alice Neel, 1984 © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. Used by permission. Courtesy: Sean Kelly, New York

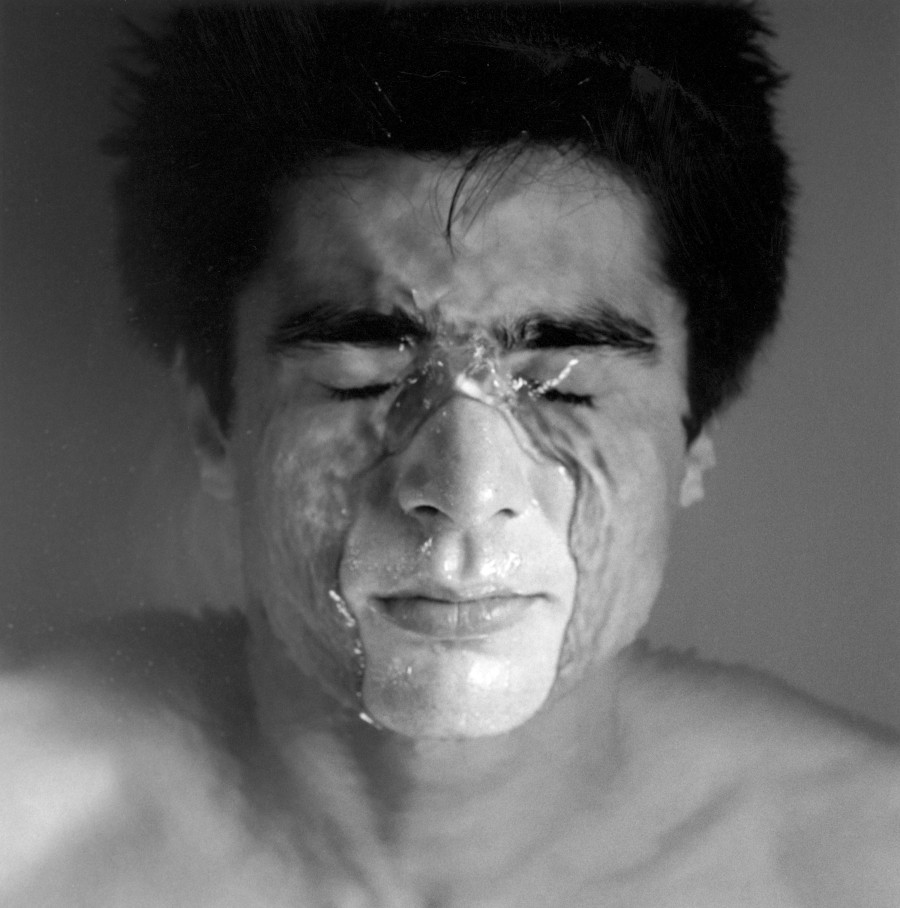

Javier, 1985© Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. Used by permission. Courtesy: Sean Kelly, New York

Courtesy: Sean Kelly, New York

Courtesy: Sean Kelly, New York

Courtesy: Sean Kelly, New York

"Saints and Sinners" runs until January 25, 2014 at Sean Kelly Gallery in New York.