Until two years ago, Jon Paul Crimi kept his career, and his client base, mostly a secret.

He has a 20-year background as a fitness trainer and used to be an actor -- but now when he gets a phone call and finds himself on an airplane two hours later heading to a movie set, he isn't going there to act.

Instead, Crimi is a professional sober coach who works with some of Hollywood’s most elite and others struggling with substance use disorders. He has been sober himself for 15 years.

“The best sober coaches are the ones who had a lot of experience struggling with sobriety," he told The Huffington Post in an interview in Los Angeles. "The further down the ladder you’ve gone and the more things you’ve been through, the more you can help people.”

Crimi is 5 feet 11 inches tall, fit and has eyes so blue that you think he must be wearing colored lenses. He is not. Crimi stands up straight, is comfortable in his body and has that kind of a smile so deeply grounded that he radiates confidence without a shred of cockiness.

But the very first thing you notice about him is that he has no eyebrows, eyelashes or hair, due to adult-onset alopecia. His Boston accent pokes out at times -- especially when he’s cracking a joke at his own expense -- which is a lot of the time. “I got kicked out of Catholic school. I had a learning disability, it was called ‘Fuck You,’” he joked, adding that he couldn't sit still in school and always felt uncomfortable.

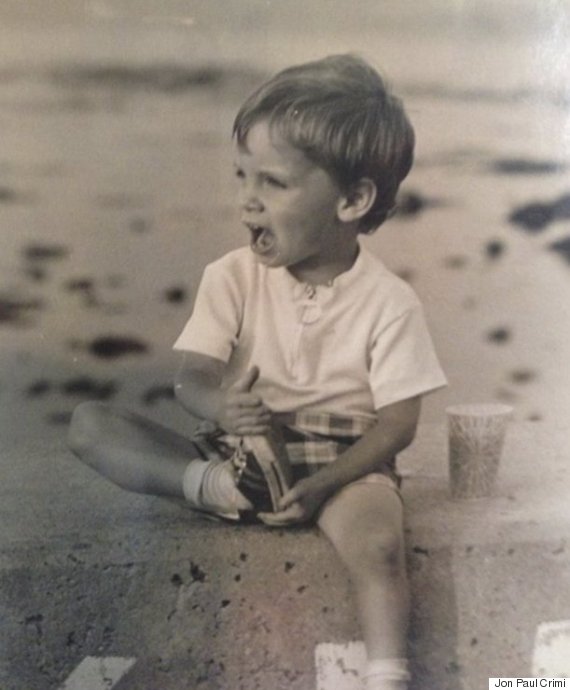

Crimi during his childhood.

“There is a big question mark about what causes drinking. Is it hereditary? Is it nature versus nurture? I think it’s both,” he said. “My joke is I’m Irish, Italian and Scottish. Which means I like to drink a lot, I don’t want to pay for it and then I want to start a fight. I’m also from Boston, and that kind of means the same thing.”

Crimi grew up in a rough neighborhood. He was jumped regularly and, in one case, stabbed. Looking back now, he marvels at how casual he was about it. The stabbing was serious -- he got 41 stitches in his head and nearly died from blood loss. Crimi, then 19, was out at a party drinking the very next night with his head wrapped in a bandage.

“Somebody said, ‘Didn’t you get stabbed last night?’ And I was like, ‘Yeah. But what’s going on with you?’”

Crimi with friends in his early 20s.

He lost a lot of friends to drugs and alcohol while growing up. Six of them. “Overdoses, suicide, car crashes. It was really hard,” he said. The people around him didn’t talk about their feelings much. He had two DUIs before the age of 21. But his best friend had four. “We call it lower companions. We seek people around us who are worse off than we are. That way we don’t have to look at ourselves,” he said.

Crimi says he didn’t know how to process everything that had happened to him. “I didn’t have any tools to deal with it. My only tool was to drink around it. If there was a bad feeling, I drank or used drugs,” he said.

Before he was a sobriety coach -- before he was even sober -- Crimi moved to L.A. with big Hollywood dreams. He was accepted to a three-year Method acting program on a scholarship. But as he began to do the work, which can be deeply emotional and draining, the trauma from his youth began to come out -- and so did his hair.

“There was one scene where someone was stabbing me and I had to stop. Processing all that in an acting class was a terrible idea.”

He began to notice bald patches all over his head, arms and legs and his doctor told him the hair loss was brought on by stress and trauma. He was put on high doses of steroids and was given excruciating shots in his eyebrows and head -- sometimes 75 or 100 at a time. He began to take Vicodin to help with the pain.

“I was 23 years old and at the peak of my life. I was trying to be an actor and my looks were everything to me. That was all being stripped away,” he said.

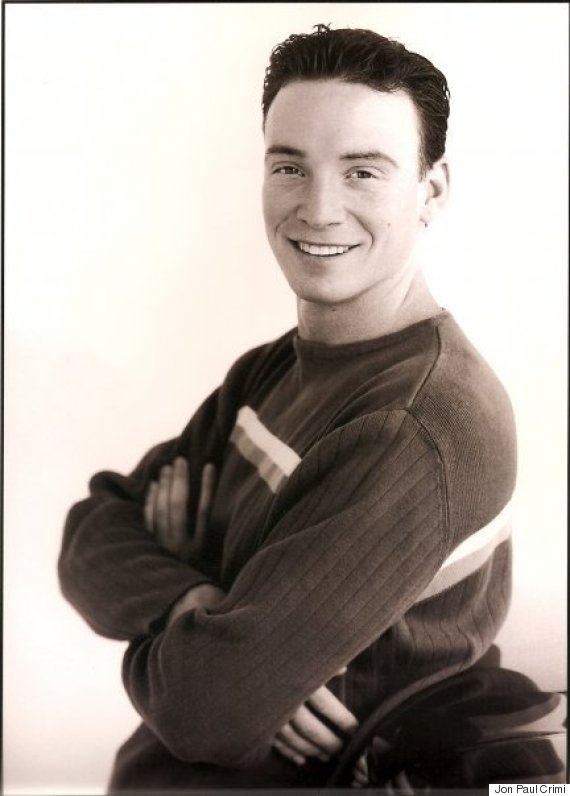

Crimi's headshot as an actor.

To make a living during acting school, Crimi trained clients and managed sales at Gold’s Gym in Venice Beach -- a famous destination for bodybuilders around the world. He was good at his job and started to snatch up some prestigious Hollywood clients. They helped him get more auditions.

But the high doses of steroids made him gain weight and bloat. “I was this fat trainer, trying to be an actor, bald patches everywhere, penciling in my eyebrows and going to auditions. I was eating Vicodin all day and drinking all night.”

His business was growing, but he was a mess.

Crimi flirted with sobriety, but didn't commit. “I would go 20 days without using or drinking and I was so uncomfortable I felt like I was crawling out of my skin. It was painful,” he said of his life at 25.

“Alcohol and drugs aren’t the problem. I’m the problem. The alcohol and drugs are my solution to the problem -- which is how I feel about myself when I don’t have anything in there. Until you fix that, you’re going to keep going back to it,” he said.

He sought out a therapist for the first time and she suggested he go to a 12-step recovery program. Crimi scoffed at the idea and tried even harder to get sober on his own. After a few months, it all came crashing down.

“Finally I bottomed out. I lost another really close friend and I went on this big bender, jumping the bridges of the Venice Canals drunk in my car. The next day, my stripper roommate told me to get help.”

He listened. When he walked into his first 12-step meeting, he realized he had been wrong. He saw young, successful people around him, saying things that he had always felt in his heart but had never said out loud.

“It rocked me to my core. I thought, ‘Wow. This is what’s wrong with me. I have alcoholism.’ It was a tough moment. But I also knew that I was in the right place for the first time in my life,” he said.

Talking about this makes Crimi choke up, even 15 years later. His eyes moisten and the rims of his eyes without eyelashes get especially red. But he also exudes a deep sense of gratitude for where he is today.

“If you’re willing to ask for help, then people will take care of you,” he said.

He worked all the steps and found a strong community of people around him. Unwisely, he continued working while he detoxed. “That’s never a good idea” he said. “I head-butted a co-worker and they let me go. The guy was kind enough to let me stay and train my personal clients.”

He built his business around his recovery. Sobriety became more important than clients and more important than making money. It’s the biggest mistake he sees people make today.

“You get sober, you start working, you get a girlfriend and go, ‘Oh, I’m good now.’ They say anything you put in front of your recovery you will lose.”

Sober coaches, who can also be called sober companions, started off in the rock and roll industry. The late Bob Timmins is thought of as the original sober companion and was described in his Los Angeles Times obituary as a “titan in the world of recovery,” particularly for rock musicians rising to fame in the 1990s.

Crimi knew Timmins personally and attributes the birth of the industry to a combination of factors. “People wanted to have their careers and play their music, but being out on the road is the one hardest places for an alcoholic or addict.” Crimi said. “There's too much temptation and they needed someone with them for support.”

The music industry is where Crimi started too. But after a couple of years of touring around the world, which Crimi says cured his rock star fantasy, he began to work with actors. It’s a business with a ticking clock: When he gets a phone call for a job, he is expected to pick up and go almost immediately.

Many of his sober coaching jobs are 24/7. He lives with the client on set and they eat together, work out together and even sometimes sleep in the same room.

But most of the time, no one else on location knows who Crimi is. “I’m the trainer, I’m the assistant, I’m the meditation teacher or I’m the bodyguard. I’ve been everything.”

It gets more complicated when the client doesn’t want him there. Many times, he is hired as a contingency of a film's insurance policy. He has had people try to lose him through airport security, use in front of him, become verbally abusive and physically confrontational.

He is the first to say that he cannot force clients to stop using. What he can do is help redirect their focus by getting them out of the room to go on a walk or take them to a meeting. He is there for support. He might help them through a meditation exercise or a gratitude list. His background in fitness helps, too. Exercise can be a big part of recovery.

“You can interrupt the disease. Even if someone is using, you can help. Some say you have to let people bottom out," he said. "But I’ve seen people who don’t want to get sober eventually get sober because they had somebody there supporting them, in their ear talking to them.”

Crimi’s mentor of 15 years, Irwin Feinberg, put it best. “Jon Paul has worked with a lot of guys who other people had given up on. He is the guy who got them into recovery,” he told HuffPost. “But it all began with him jumping into his own recovery with both feet.”

Part of Crimi’s job is borne out of the limitations of rehabilitation facilities. “It’s a cushy bubble,” he said. “Then they go home and all of their triggers come up that made them want to drink or do drugs before. It’s about helping them in their environment but it’s also about helping them re-create their lives.”

A good number of his clients have been drinking or using for most of their lives. They don’t know what to do sober. They don’t know how to handle Christmas or New Year’s sober. They don’t know how to handle a death in the family. Crimi helps them implement new habits.

But the most powerful tool in his own recovery and what he stresses the most with clients is to focus on helping someone else. That’s why when he was first sober, he joined the Big Brother program and became a mentor.

“I had really low self-esteem when I got sober. It was my first estimable act. It builds you up. When I am helping someone who is going through something, I cannot be in my problem. The faster you can do that, the better off you are,” he said.

John Hanney has worked with Crimi for the last nine years and says that his life has been re-created as a result of their relationship. “I was quite possibly one of the worst cases that anybody had ever seen,” Hanney told HuffPost over the phone. He tried to get sober for 17 years.

“Jon Paul has helped me recover from this disease one day at a time. I could trust him and could disclose my deepest, darkest secrets to him. It took time but he instilled confidence in me,” he said.

Many sober coaches don’t have families. The unpredictable lifestyle and expectation that you can be gone for weeks or months at a time aren’t exactly conducive to building relationships at home.

Crimi with his daughter, Mika.

But Crimi is the exception. He has been married for six years and has a 2-year-old daughter. He is on the road less and less, and is building his company to train sober coaches to take the out-of-town work so that he can be home with his family. Being a father has presented a new list of challenges for him.

“I worry about genetics. Am I going to pass this on to her? I see her doing things like spinning around and around in circles and I’m like, ‘Oh my God, she’s trying to get high!’”

His wife, Nomi, tells him it’s just a toddler thing. “My wife is not an addict. She’s a totally normal person. She calms me down.”

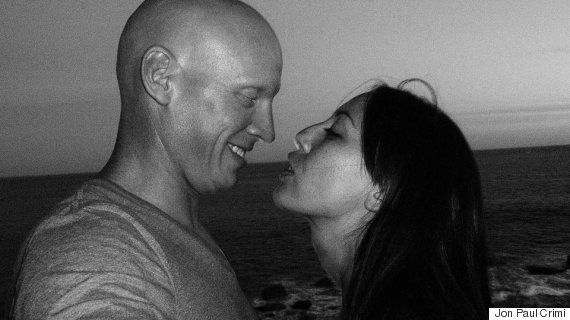

Crimi and his wife, Nomi.

Aside from being grounded by his family, Crimi's deepest source of strength ultimately comes from paying it forward. It's what connects him most fully to a sense of spirituality. “For the longest time my spirituality was simply helping other people. I don’t know anything more spiritual than helping someone and expecting nothing back,” he said. Being vulnerable and letting clients see who he really is can be just as powerful a tool.

“That’s what puts people at ease with me. When you open your heart to someone, they see that. They connect to you,” he said. “That’s spirituality to me. That’s God. That’s love. And for an East Coast former tough guy to say something like that is a miraculous thing.”

Jon Paul Crimi’s company also works with dual diagnosis clients, such as those with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression and traumatic brain injuries. More information can be found on his website.