The drug known as Spice is becoming more potent and dangerous since it was outlawed by the government last year, fuelling an explosion in incidents linked to the substance, a range of experts and authorities in Manchester have said.

Spice, a synthetic cannabinoid which hit headlines last week for causing ‘apocalyptic’ scenes in the city centre, has now become the preserve of organised crime leaving fewer clues as to its true chemical composition.

Drug researchers working alongside police have reported a dramatic rise in the strength of the narcotic since it was outlawed, while social workers have described a current batch on the streets as “really, really dangerous”.

“The government didn’t really think through the consequences of banning Spice and criminalising the supply of Spice,” Tony Lloyd, Manchester’s Police and Crime Commissioner and interim Mayor, told The Huffington Post UK.

“It should have been thought through as to what the impact would be if it lead to less control over supply.”

Previously, while Spice and its variations were considered dangerous, they were sold by online stores and in head shops where supply chains were more easily tracked and controlled. Some products carried detailed labelling.

But the drug, newly classified as Class B, Schedule One, has now become notorious after shocking scenes from Manchester’s central Piccadilly district were splashed across newspapers last week.

Nearly 60 incidents linked to the use of Spice were reported in the area in just three days last week, with users throwing up and passing out in the streets, or being pictured in a catatonic state.

On one evening, 15 simultaneous Spice incidents occurred, stretching emergency services to near ‘crisis-point’, a local MP said.

What is Spice?

Spice emerged as a ‘legal high’ in 2004, and began making headlines several years ago after its use became prevalent in prisons and among recreational users.

Legal highs were linked to a sharp rise in inmate violence and deaths in Britain last year, with warnings that drugs such as Spice were triggering psychotic episodes and even suicide.

Spice is a synthetic cannabinoid - often referred to as synthetic cannabis or man-made marijuana.

It is now a Class B, Schedule One drug - with intent to supply carries a maximum sentence of 14 years’ imprisonment and a fine, according to Release.

Dr Oliver Sutcliffe, Senior Lecturer in Psychopharmaceutical Chemistry at Manchester Metropolitan University, explained to HuffPost UK how synthetic cannabinoids work on the body:

“Man-made cannabinoids were either designed by chemists to probe the cannabinoid receptor which is in every cell in your body [for potential therapy], or also to develop molecules that could be used to wean people off cannabis addiction.

“Now, with the internet, and access to literature, people are looking at compounds that are active on the cannabinoid receptor and whether they get around the Misuse of Drugs Act.

“The cannabinoid receptor is like a lock, and a natural cannabinoid, say found in cannabis, will fit into that lock like a key, it will turn and produce a response.

“This is the same with synthetic cannabinoids, which may not look the same, yet they will still go into the lock but may even be efficient at fitting into the lock and producing a response.

“So you may get a more pronounced response because it fits in better. And if you have more, a greater concentration, you will get to a point where it will have a huge effect - before it becomes toxic.”

“It should have been thought through as to what the impact would be”

- Tony Lloyd, interim Mayor of Manchester

“The way it’s happened meant [we’ve gone] from having a fairly regulated trade in the past [when] if a bad batch of Spice came through then, before the legal ban, the police or others could prevail on the local suppliers, and through them the supply chain, and say ‘Get that off our streets’,” Lloyd said.

“But now of course with the illegal trade there is no capacity to say ‘Please would you’d be kind enough to remove that from our streets,’ so it makes it much more random.”

Chief Superintendent Wasim Chaudhry of Greater Manchester Police (GMP) told HuffPost UK: “I do think that because of the fact now it’s being manufactured by, potentially, drug dealers then it cannot be controlled.

“The fact that it is being mixed in places, potentially in people’s homes, there is absolutely no control. We don’t know what it’s being mixed with and therefore the effect on the user is particularly concerning.”

“We don’t know what it’s being mixed with and therefore the effect on the user is particularly concerning”

- Ch Supt Wasim Chaudry, Greater Manchester Police

And while Chaudhry pointed out the problems with an underground supply chain, he welcomed increased powers for police to tackle the production and dealing of the drug.

“We are clear we are going after and targeting the dealers and producers,” he said.

Julie Boyle of Manchester homeless charity Lifeshare, said those taking Spice were vulnerable to attacks and sexual assault.

She told HuffPost UK: “The effects of Spice at the moment are that people are frozen, it looks like you’ve pressed pause on the TV. I saw two guys standing still and another guy going through [his] pockets.

“[He] didn’t flinch, he didn’t move. It’s very, very dangerous. They are vulnerable to attacks, robbery, sexual assault, so it makes them in [a] frozen state, where they’re not aware of what’s going on.

“They can fall on their face because they don’t put their arms out, they fall backwards because they can’t stop themselves.

“This batch that’s out at the minute is really, really dangerous.

“...it makes them in [a] frozen state, where they’re not aware of what’s going on.”

- Julie Boyle, Lifeshare charity

“It’s changed since the ban because it’s now being sold at street level, so lower-level street dealers [are now involved]. It’s being homemade and we don’t know what’s in it. People aren’t bothered about a Class B drug.

“People openly smoke cannabis around the streets, so that’s the same thing that’s happening with Spice. There’s not the enforcement to stop people.

“It’s not made things any better,” the 46-year-old said about the ban. “It’s making people do things they’ve never done before... steal things they’ve never done before... do sex work they’ve never done before.”

Ch Supt Chaudhry’s colleague Inspector Phil Spurgeon also questioned the ban, telling the Manchester Evening News last week: “The product was probably more consistent in the head shops [where legal highs were sold].

“Now it’s more varied, the makeup is constantly changing. That’s why we’re seeing people collapsing, as the drug becomes more potent.”

That theory is one being explored by chemical researcher Dr Oliver Sutcliffe of Manchester Metropolitan University (MMU), who is working with GMP to analyse samples of Spice as they are taken from the street.

In samples taken so far in 2017 the proportion of cannabinoid to herbal blend, or the potency of the product, has varied wildly from 0.4% to 18.7%.

Before the ban, consumers would choose products based on their strength - today, there is no way of knowing how strong a packet of Spice may be.

Importantly, the research has thus far ruled out a potential mix with another drug or tranquilliser.

Sutcliffe explained that the cause of the recent spike in incidents is likely a combination of the potency of the man-made cannabinoid, its design in creating a psychoactive effect on a user, and how it is administered.

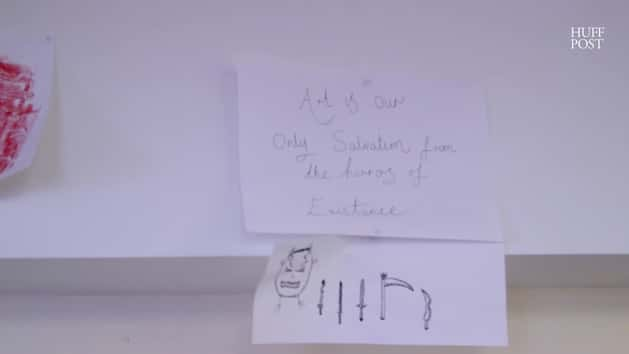

“When the head shops were operating and the online stores you could potentially get more information - not that it was correct - but you at least had something you could refer back to and know what the potency is,” Sutcliffe said. “But now, with [today’s forms of Spice], they look like snap bags with a herbal blend. You can’t tell if you’ve got a good batch or a bad batch.”

The situation was predicted by former government drugs advisor Professor David Nutt in a blog on HuffPost two years ago.

“Head shop owners usually test out their products on themselves and only sell those that they know to be enjoyable and safe,” Nutt wrote in 2015. “When a market is driven underground or into the internet [all] semblance of quality control is lost.”

“The whole thing was utterly predictable,” Nutt said this week. “The trade has passed from the head shops to the street dealers – and on the black market people don’t care whether their ‘customers’ live or die.”

Manchester Central MP Lucy Powell this week appealed to Home Secretary Amber Rudd to tackle the problem. She too highlighted last year’s ban on legal highs.

“Following the implementation of the Psychoactive Substances Act, supply of the drug has shifted from the shops onto the streets, and with its content now difficult to identify, it’s both astonishingly cheap and increasingly potent,” she wrote.

“...it’s both astonishingly cheap and increasingly potent”

- Lucy Powell MP

And Sutcliffe’s MMU colleague, criminologist Dr Rob Ralphs, went as far as to describe Spice as “the new heroin” among younger homeless and rough sleepers in Manchester.

“Anecdotally young people would say to me, ‘I know it sounds daft but when I use it I feel warm, it’s like having a warm blanket round you,” he said. “They talk about the withdrawal, committing acquisitive crime, in the same way others have talked about an opioid.

“It’s referred to as a synthetic cannabis but they aren’t using it to chill out, they’re using it to block out,” he said.

“...they aren't using it to chill out, they're using it to block out”

- Dr Rob Ralphs, Manchester Met University

“Last night, I was out with an outreach team and it must have been less than 50 percent of those we spoke to said they had used Spice,” Ralphs added. “There will be squats where they won’t let anyone smoke Spice, those where they take heroin, others that are abstinent.”

Sutcliffe and Ralphs said the problem appears more acute in Manchester in large part due to the layout of the city.

Piccadilly Gardens, the area favoured by rough sleepers, is in “plain sight” and the heart of main thoroughfares and transport hubs, they said.

But problems with Spice are not limited to the city. Earlier this week, a homeless man died in Birmingham after using a variant named Black Mamba.

And there have also been reports of incidents linked to the drug in Westminster, Leeds and Blackpool - all areas with high homeless and rough sleeping populations.

Government Minister for Vulnerability, Safeguarding and Countering Extremism Sarah Newton said: “Drugs can devastate lives and communities; we will not tolerate them in this country.

“That is why last year we passed the Psychoactive Substances Act to outlaw so-called ‘legal highs’ and introduced even tougher controls for synthetic cannabinoids, such as those found in Spice – people found in possession of it can now be jailed for up to five years.

“We are also tackling the harms caused by illegal drugs.

“Our Drug Strategy, to be published shortly, will build on the work already undertaken to prevent drug use in our communities and help dependent individuals, including homeless people and those in prisons, to rebuild their lives.”