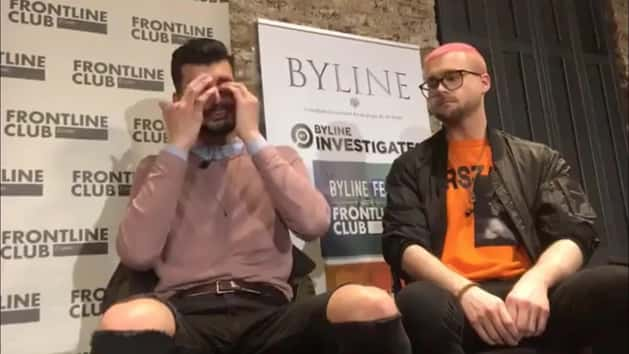

Vote Leave whistleblower Shahmir Sanni broke down in tears on Monday evening as he talked of being outed by Theresa May’s political secretary, Stephen Parkinson. Sanni, who claimed the EU Referendum “wasn’t legitimate”, had not come out to many of his friends and family, but in a public statement, Parkinson revealed he and Sanni had been in a “personal relationship”.

Sanni said members of his family in Pakistan have been “forced to take urgent protective measures to ensure their safety” because of his public outing. Wiping away tears from his eyes, he added: “I came out to my mum the day before yesterday. He [Parkinson] knew. He knew I wasn’t out to mum.”

LGBT charity Stonewall has called what happened to Sanni as “inexcusable”, adding: “Publicly outing someone robs that person of the chance to define who they are in their own terms, if they even want to. In extreme cases - as in this one - it can also put the lives of that person and their loved ones in danger.”

But sadly, public outing is something many LGBT+ people have to face every day.

Arün Smith, 29, who identifies as a “queer, racialised, cisgender man”, was outed when he was at his first gay pride parade with his then-boyfriend at the age of 17.

“A TV cameraperson panned across the assembled crowd, revealing that I was there. I was not marching in the parade, but rather, simply spectating because I was not yet publicly out, nor was I at a point of comfort with my identities to participate,” Smith, from Calgary, Canada, told HuffPost UK. “One of my grandparents’ friends saw the shot on the news, and because Calgary’s Indian community tends to be tight-knit and gossip-filled, informed them.”

Smith was “devastated” at being outed before he felt ready, especially as it led to him being kicked out of his house. “I spent the summer living with friends and trying to figure out what to do, and how to live. I was almost unable to return to finish my last year of high school, which, obviously, would have had massive consequences,” he said.

After Shahmir Sanni’s story broke, Stonewall said the decision on whether to come out or not varies from person to person and is sometimes influenced by the community you live in. Fear of discrimination at work or in a place of worship can impact someone’s decision.

“Outing someone ignores the many valid reasons a person may have for not choosing to be open about their sexuality to every person in their life,” the charity said. “Some LGBT people are not out because of a real need to protect themselves. We do not live in a world that is accepting of everyone’s sexual orientation or gender identity.”

Ollie James-Parr, now 32, was also outed when he was still a teenager, as an 18-year-old student. He’d come out to a friend at college and shared private details about his life, but the friend then betrayed that confidence to someone else.

“I hadn’t known that this person had gone on to tell a large number of my peers, and it only came to light after a comment on the football pitch during PE, which made it abundantly clear that intimate details I had originally shared confidentially had become public knowledge,” James-Parr, from London, told HuffPost UK. “I felt devastated, because effectively I was no longer in control of my narrative, in control of something which, at the time, I felt could have the potential to ruin my life, added to the fact that I was still coming to terms with who I was.”

James-Parr said he feels fortunate he didn’t experience much abuse or ridicule beyond the football match, which is testament to “how well the college was run”. But he is all too aware that “in a different environment or location things could have been a lot worse”.

According to Stonewall, LGBT+ people continue to face “alarming levels of abuse and discrimination in both their public and private lives in Britain and abroad”. One in five LGBT+ people (21%) have experienced a hate crime or incident due to their sexual orientation and/or gender identity in the last 12 months. “Even within the LGBT community, trans and bi people are exposed to transphobia and biphobia that uniquely impact their experiences of coming out, or not,” the charity said.

Both James-Parr and Smith wanted to stress the seriousness of outing someone.

“Outing someone is a reprehensible act, even more so when you are aware that there could potentially be negative consequences in doing so,” James-Parr said. “As an LGBT+ person you are presented daily with situations whereby you have to make the decision as to whether to out yourself, be it in the workplace, in a sports arena or simply holding someone’s hand in a public place. It’s a complicated and ongoing issue for all LGBT+ people because we have to judge whether, in doing so, this would negatively impact our lives.”

Smith added: “For me, because I don’t know on any given day how someone is going to react to who I am and how I present, it’s vital that I have control over the narratives of my own exposure to the world. This is at the core of why outing is so dangerous; it denies people agency over their own lives, puts them on public display, and makes their identities subject to public scrutiny.”