This week the Census Bureau reported the latest depressing decline in middle-class incomes during the so-called economic recovery. But it may have missed an important factor in this story.

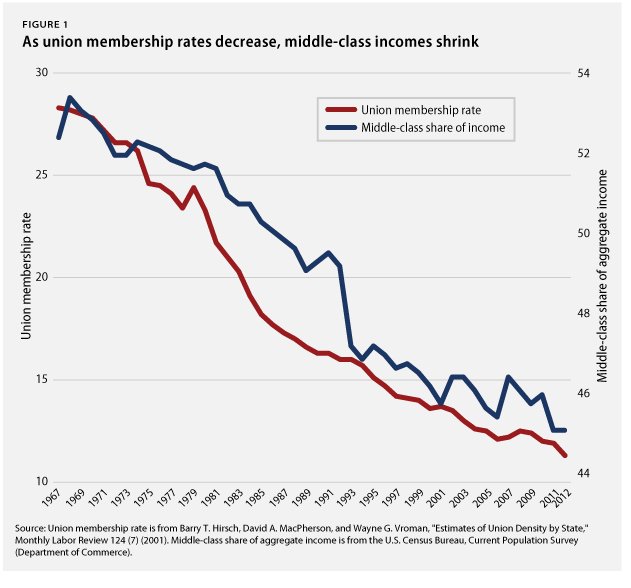

A report on Wednesday from the left-leaning think tank Center For American Progress notes that as middle-class incomes have steadily fallen, so have union membership rates. The middle 60 percent of households earned 53.2 percent of national income in 1968. That number has fallen to just 45.7 percent. During that same period, nationwide union membership fell from 28.3 percent to a record-low 11.3 percent of all workers.

Put these two economic trends together, and a striking image appears:

Indeed, declining labor-union participation is not the only factor killing middle-class income growth. But increased union participation would likely mean more income for the middle class, the left-leaning think tank Economic Policy Institute argued in a 2009 report. Unions typically increase the wages of their workers while also raising pay for nonunion workers in industries with a strong union presence.

Higher union participation rates might also reduce income inequality. The U.S. has the worst income inequality of any county in the developed world, and the nation's top earners continue to see their pay rise as median incomes fall. Union participation could counteract this trend, according to the EPI.

So why is union participation declining so rapidly? Private sector union membership reached a peak of about 35 percent of the labor force in the 1950s, The New York Times reports. Since then, labor unions have steadily become smaller as many states have rolled out new laws limiting union power.

Young millennials' disenchantment with organized labor may also be an important contributor to its decline. From 2002 to 2012, union members ages 16 to 24 fell by 26 percent. That's double the decline in union membership for all workers, according to Quartz.

That said, younger generations may have a good reason to be less than eager to join a union. Studies have discovered that during the economic recovery, non-union workers fared considerably better than union workers in fields like manufacturing and private construction. Also, during the 1982 and 1991 recessions, states with fewer union members were found to recover more quickly than states with a strong union presence.