They’re large, they’re furry, and their buzzing is notoriously loud – we’ve all been forced to swerve once or twice as one narrowly misses our head.

But, bumblebee populations are in rapid decline. You might’ve noticed that as each year passes, our skies, gardens and parks are quieter, with glimpses of those yellow and black bulbous bodies being few and far between.

In the past century, the UK has witnessed two species of bumblebee go extinct, while many more are listed on priority species lists. In short: our big furry friends are in crisis.

A new study from the University of Ottawa suggests that in the course of a single human generation, the likelihood of a bumblebee population surviving in a given place has declined by an average of over 30%.

Worryingly, researchers said these bees are disappearing at rates “consistent with a mass extinction”. So is there any way to prevent it?

Why should you care about the bumblebees?

Aside from them being pretty cute, they’re also important for our existence. “Bumblebees are the best pollinators we have in wild landscapes,” said one of the study’s authors Peter Soroye, a PhD student from the department of biology at the University of Ottawa.

Without them, Darryl Cox, senior officer for the Bumblebee Conservation Trust, says nutritious food-stuffs like tomatoes, beans, peas, apples, strawberries and raspberries would be harder to produce – and more expensive as a result. A future with fewer bumblebees means less variety of plants and flowers outdoors, as well as fewer food options.

“Bumblebees are key to many complex food chains in the natural world,” explained Cox. “They help many plant species reproduce through pollination, these plants form the base layers of whole ecosystems, providing food and shelter for numerous other species. If declines continue at this pace, many of these species could vanish forever within a few decades.”

What else did the study find?

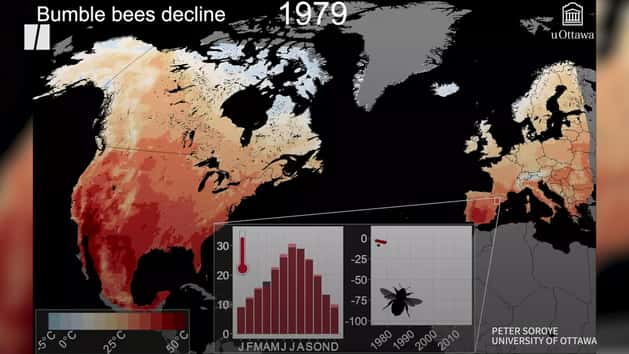

The University of Ottawa study looked at how climate change increases the frequency of extreme events like heatwaves and droughts, creating a “climate chaos” that is dangerous for animals, including bees.

Knowing that bumblebee species have different tolerances for temperature – what’s too hot for some might not be for others – the researchers created a way to predict local extinctions that tell us, for each species individually, whether climate change is creating temperatures that bumblebees can’t handle.

Using data on 66 different bumblebee species across North America and Europe, collected over a 115-year period, the researchers were able to see how bumblebee populations have changed by comparing where bees are now to where they used to be historically.

“We found that populations were disappearing in areas where the temperatures had gotten hotter,” said Soroye. “Using our new measurement of climate change, we were able to predict changes both for individual species and for whole communities of bumblebees with a surprisingly high accuracy.”

He added: “We have now entered the world’s sixth mass extinction event, the biggest and most rapid global biodiversity crisis since a meteor ended the age of the dinosaurs.”

Is it all doom and gloom?

No, it’s not. But it’s a wake-up call. The study’s findings could help scientists prevent extinction in the 21st century, said Jeremy Kerr, professor at the University of Ottawa.

One solution could be to maintain habitats that offer shelter like trees, shrubs, or slopes, that allow bumblebees to get out of the heat, he added.

“Ultimately, we must address climate change itself and every action we take to reduce emissions will help. The sooner the better. It is in all our interests to do so, as well as in the interests of the species with whom we share the world.”

What action can you take right now?

Cox, from the Bumblebee Conservation Trust, wants people to cut the grass less often (once every three weeks is fine) and turn a blind eye to the odd weed here and there, particularly in spring when fewer plants are in flower. Perfectly cut grass deprives pollinating insects of the wildflowers they need to feed on

You could also grow bee-friendly flowers throughout the year, especially between March and October when most bumblebees are active, he adds. For flower suggestions, try the free Bee Kind tool. Bees love the common poppy, foxglove, nasturtium, teasel, and lavender, as well as herbs like chive flowers and lemon thyme.

In keeping with the study’s findings, it might also be worth filling your garden with bigger, leafier plants so bumblebees can find shade if they get too hot.

If you want to encourage bumblebees to nest, try putting up a bird-box or installing a hedgehog hibernation box, says Cox. The latter can be dual purpose – hedgehogs sleep in them over winter and bumblebees nest in them in spring and summer.

You could get involved with conservation, by helping count bumblebees and other pollinators in your back garden with the UK Pollinator Monitoring Scheme. Or set up a monthly BeeWalk to work out how bumblebees are responding to things like climate change.

“Perhaps you could help raise funds for bumblebee conservation projects,” suggests Cox. “Maybe run a race, have a dress-down or non-uniform day, or hold a bee-themed cake sale.”

Ultimately, tackling climate change is in everyone’s best interest. According to Friends of the Earth, the best way to do this is by putting pressure on the government to act urgently.

Switching to green energy, using public transport, cycling instead of driving, and taking trains instead of planes are other simple ways to help.