If you’ve recently become a caregiver to a small human, you might notice minor lapses in your memory. For example, you might find yourself wandering around a parking lot trying to recall where your car is. Or perhaps you walk into the kitchen and open the refrigerator only to hang there in the cool air as you try to remember what it was that you came in to get.

Such moments are sometimes referred to as “mommy brain.”

Elizabeth Werner, a clinical psychologist and researcher at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center who specialises in perinatal mental health, told HuffPost: “‘Mommy brain’ is a term that is used to describe the cognitive changes and challenges that many people report experiencing during pregnancy and the months following giving birth. Many people describe feeling more forgetful or having ‘brain fog.’”

These kinds of experiences can be frustrating and may cause you to worry about your ability to manage the demands of parenthood — especially if you’re planning on juggling those alongside paid work.

The good news is that such lapses are normal and just one small part of the shifts that are going on in your brain as it adapts to this new role in your life.

This state of flux has its disadvantages and can make you vulnerable to anxiety and depression. Indeed, we know that about 1 in 7 new birthing parents (and a number of non-birthing ones as well) experience postpartum depression. At the same time, your brain is priming itself to meet the rigours of caregiving.

Liisa Galea, a senior scientist at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health in Toronto, told HuffPost: “It’s a heightened period of concern because you have this new baby you’re trying to take care of, but what we’ve often said is that it’s almost like superpowers: You’ve given birth to a baby, but you’re learning all these new things.”

How does parenting change the brain?

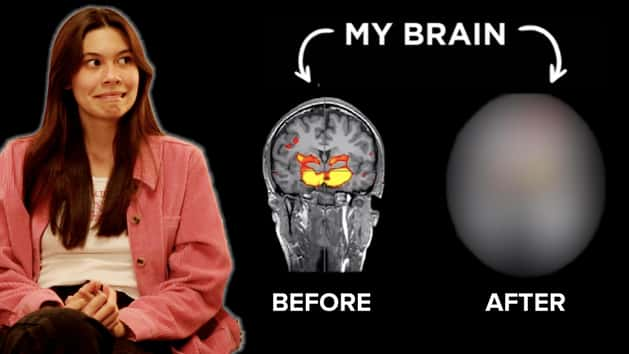

If you’re familiar with the concept of “mommy brain,” you may have heard something about “losing brain cells.” This is likely a reference to research that shows “volume loss” in parents’ brains. It’s tempting to hear this and connect it with lapses in memory, but the reality is more complex.

“In humans, we do see grey matter loss and brain cell loss, or reductions, during pregnancy, but they’re not related to memory,” Galea said. She noted that the overall size of the brain doesn’t change, that loss in one area can be compensated for by growth in another

“It’s not like, ‘Oh, the more brain cells you lose, the more memory you lose.’ There’s actually no evidence to support that. But there is evidence to support that it is related to maternal care.”

Rather than shrinking, the brain is changing and adapting in a way that supports a person’s ability to care for a child.

Chelsea Conaboy, an award-winning journalist and the author of “Mother Brain: How Neuroscience Is Rewriting the Story of Parenthood,” compares the way the brain changes in parenthood with the way it changes during adolescence. (She is also careful to note that brain changes occur not only to gestational mothers but also fathers and other primary caregivers.)

Conaboy writes: “The teenage brain is far more studied than the maternal brain, and it is generally accepted that a reduction in grey matter in adolescence represents a fine-tuning of networks ... meant to help teens adapt to life as adults — not a loss in brain function.”

She explained to HuffPost that research on the brain shows parenthood to also be “a really adaptive time of life. Your brain goes through really dramatic changes.”

These shifts bring about “heightened cognitive skills,” she said, “that allow you to engage in this new role as a parent, which is really complicated and taxing and requires you to do things that you’ve never done before.”

“One of the big messages in the parental brain research is that we fine-tune our social cognition so the brain changes that that we go through basically help us to get better at reading the mental state and emotional cues of other people, and specifically our baby, and responding to them.”

It seems unlikely that these new skills would be limited to interactions with our own children. Perhaps parenting can help us become more finely attuned to everyone else around us.

What do we know about memory and parenthood?

Memory, of course, is affected by a multitude of factors. What is our motivation? Are we getting enough sleep? Are we under stress?

Lapses that we might attribute to “mommy brain” are more likely to be the result of distraction, Galea said. “If you bring people into the lab to to test their memory, there are very, very, very few deficits at all during pregnancy.” It is when researchers “ask them things like, ‘Hey, here’s an envelope that’s pre- stamped. Mail it in a week,’ that’s when they do badly. You go home, you’re distracted, there’s a million other things.”

If you were someone who had to parent while working at home during the coronavirus pandemic, you can appreciate how impossible it felt to think clearly and function well in the middle of such chaos.

There are also the factors of sleep deprivation, which is very real to new parents, and mental health issues, such as depression and anxiety, which we know may also cause memory issues.

Though some studies have found small deficits in memory during pregnancy or the time immediately following birth, this doesn’t apply to all kinds of memory, and it doesn’t seem to last. Galea points to studies in rodents that show by the time the pups are a bit older, the mother’s memory is in fact enhanced.

Yet the story that caring for children is bad for your memory persists, both because there are times when it feels true and because the research that we have is both limited and sometimes appears contradictory. For example, we know that women, who are likely to both experience brain changes in pregnancy and spend significant time caring for children, are at a significantly higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease than men. Yet studies of a large number of brain images collected in Europe found that women who had children actually had “younger looking” brains than those without children when the volume of certain areas of their brains were measured and compared. So the changes that parenting makes to the brain may persist and act as a protective factor even decades later.

How much should a person be able to remember?

In a 1956 paper widely referenced in psychology (and beyond), George A. Miller proposed the following theory regarding human memory: “the magical number 7 plus or minus 2.” This was his summary of the finding that, in their working or “short-term” memory, a human being can hold about seven “units” of information. For example, if someone was giving you random words or letters to recall, you would be able to handle a list of five to nine items. There are tricks you can use to extend this limit, such as “chunking” information into pieces or using mnemonic devices, but the fact remains that there is only so much we can keep in our working memory at one time.

The bigger picture of human memory — what we retain in the long-term, how it is connected to senses like sight and smell — is of course much more complex, but given that the intensive demands of parenting often involve far more than seven bits of information, perhaps we should all go a little easier on ourselves. If you can’t remember where you put your wallet, it is probably not a symptom of cognitive decline — it’s more likely that you are simply trying to remember too many things at once.

“Be kind to yourself, and recognise how difficult it is to manage the complex demands of this period in your life,” Werner said.

How to deal with forgetfulness.

The human brain is adaptive, but the process by which it changes is more complicated than, for example, strengthening a muscle with repeated exercise. There are, however, some things that you can do to help you cope when you find yourself forgetting things more than usual.

If you’re not getting enough sleep, it will affect both your memory and your functioning overall.

“Figuring out ways to get more sleep ― and specifically longer stretches of sleep ― can be helpful for your memory, your level of functioning and overall mental health,” Werner said, adding that it can make a big difference to get some help with nighttime infant care. Handing one feed over to someone else can make a longer stretch of sleep possible for you.

When it comes to things you’re liable to forget, it can help to make lists and to set reminders or alarms on your phone. For example, if the trash gets picked up early every Monday morning, you might set an alert to go off at 10 p.m. every Sunday to remind you to take it out to the curb.

Finally, if you’re struggling emotionally, it’s critical to reach out for support. Talk to your doctor or midwife about any symptoms of depression or anxiety that you may be experiencing.

If you do experience some trouble with memory in those last months of pregnancy or those first months of parenting, instead of berating yourself, think of it as your brain’s way of sending you a signal, Galea suggested: “It is hard at the beginning, and your body is telling you to slow down. And I think that’s a really important evolutionary message that your body and brain are probably saying, ‘Hey, you don’t need to go anywhere. You just need to be here in the moment.’”